“The town of everlasting festivity.” That, we were told, is what is says on the Municipal coat of arms of Tuxpan, a town in the south of Jalisco almost on the boundary with the neighboring state of Colima, and relatively close to the Mexican Pacific coast.

We arrived at Tuxpan in the morning of a sunny Good Friday. Our first stop was City Hall. We wanted to verify for ourselves the accuracy of the famous motto, which we had previously only read about. Where else to find it if not at the seat of the local government? To our good fortune, we stumbled across frontline police officer Heraclio Jiménez, who, with the best good humor in the world, answered all of our inquiries, starting with the coat of arms. A good-sized reproduction in limestone repeated to us the phrase we were looking for. I could not help but ask, “Excuse me, don Heraclio, are there any festivities today here in Tuxpan?” He answered with a smile, “Don’t you see, my friend, that here fiesta is eternal?”

We had left Guadalajara very early (Tuxpan is a little over an hour and a half from the city, via the toll road to Colima and Manzanillo), without having breakfast. On a recommendation from don Heraclio we headed towards the local market, a couple of blocks ahead. “Climb to the upper story by the side stairway. Ask for Carmelita. Clean and tasty.” On our way to the marketplace we passed across the plaza in front of the church. We passed by the Plump Cross. The morning light was perfect, so I asked my companions for time and patience to take a photo of this monument, a symbol of the evangelization of the Nahuatl peoples of the region. This cross, named “queen of all crosses,” was erected in the year 1536. Father Juan de Padilla, Guardian of the Convent in those days, managed to get some architects sent by order of the viceroy to bring the plan of a similar cross erected in Huejotzingo, Puebla. Based on that idea the Plump Cross was sculpted and placed here. After a couple of photos, the friendly pressure: “Hunger is in the air. Let’s go.”

We went for breakfast. Carmelita was charming, her menu for Lent superb. Shrimp pancakes with prickly pears in mildly hot red sauce; huevos rancheros and güero (blond) beans, a traditional regional dish, accompanied by freshly handmade tortillas and homemade guava quencher. Delightful! As it was the time for Lent abstinence we weren’t able to enjoy coaxalas, a flavorful stew made with shredded chicken in purple tomato and guajillo pepper sauce, a dish that originated in Tuxpan; nor the pasilla moleso loved by locals and foreigners. Well, we’ll leave those for another day.

Stuffed, and with a song in our hearts, we resumed our visit. We went across the atrium and the square in front of the church again. At the far end, laid as a frize on a lateral building, we admired the retablos positioned there on the occasion of the Holy Week and Easter celebrations. A multitude of shapes, colors, fruits, bottles, flowers and figures reminded us of the important indigenous presence among Tuxpan residents.

We entered the church and asked for the events of the day. A very kind lady, seller of relics, images and other religious items at the entrance, informed us about the main happening: the procession of allegorical carriages which was to take place, starting at the atrium and then around town, between one and two o’clock in the afternoon. Relaxed, and with time on our side, we calmly explored all over the church and its annexes.

We found there, as it is now common in the Cristero areas of Jalisco and other central and western Mexican states, an image of San Toribio Romo, patron saint of migrants. Many stories travel around Mexican towns and villages about this saint, now dead for more than 90 years, who materializes to migrant workers in extreme situations in order to save them from mortal danger when illegally crossing the border. This has contributed to make this priest—cowardly murdered by federal soldiers in 1928 near Tequila, Jalisco—the most popular of the martyr saints from la Cristiada; he was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1992. Many believe that the interest and the protection extended by the saint come from the abuse and persecution he suffered in life, something with which our frequently harassed and mistreated migrants can identify.

We invested our remaining time in a long walk up to the railway station, in part to get more acquainted with the town, in part to help us burn the generous breakfast offered by Carmelita. We didn’t find an interesting building anywhere. Solid architecture; broad, well traced paved streets and everything sharp and clean, but the harmony and beauty found in many Mexican towns were completely absent. Vivid colors abounded: intense reds, emerald greens, blues, pinks and yellows, the Nahuatl personality heralding itself in facades, walls, doors and windows.

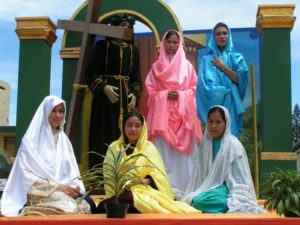

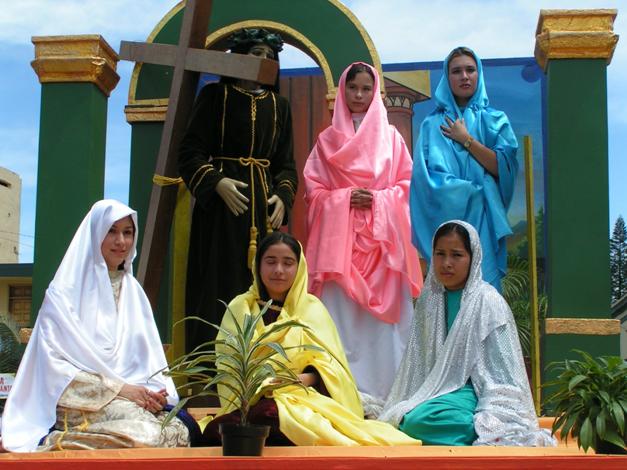

We came back in time to the atrium. The multitude was already crammed around the allegorical carriages. On platforms installed on pick-up and heavy trucks, or on trailers towed by tractors, there were religious scenes in accordance with the holidays: staging of the Passion and representations of Stations of the Cross; actors gesticulating and speaking to the people through microphones and amplifiers conveniently installed for the occasion.

Pilate sentenced Jesus Christ at the top of his voice: “I, Pontius Pilate, president of Jerusalem, rule and decree Jesus Nazarene to be crucified for being a false prophet, deceiver of the people, disturber of the Republic, spreader of false doctrines and necromancer.” On top of a fine chestnut mare, a representative of the people, boasting a cowboy hat and dressed in rigorous black, scolded him: “Be afraid, Pilate. Live knowing that in the end you will pay with eternal punishment for your ambition and your injustice.”

One by one the carriages left the atrium, followed by their particular band of wind and percussion instruments, their Judas and crowds, to cover the streets of Tuxpan. The last one finally departed. That, for us, was also the sign to depart. It took us some time to find the exit to Guadalajara, because the processions filled the streets.

Back on the highway we took notice of the joyful and content state of our spirits. Surprised, we tried to understand the reason for our elation. We soon found the answer: the kind and agreeable people we had met and interacted with in Tuxpan. People, not buildings or monuments, is what gives a town the ability to maintain the flame of fiesta alive for ever.

Want to learn more about Good Friday in Mexico?

- Easter in Mexico, Semana Santa and Pascua: a Mexican holiday resource page

- The passion of Christ in Ixtapalapa, a Mexico City neighborhood

- Semana Santa Holy Week in San Miguel de Allende

- Good Friday in San Miguel de Allende in the 1960s

- The food of Easter in Mexico: a seasonal celebration of popular cuisine