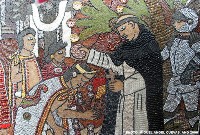

Step by step, all roads are formed by those who walk them. The roads of Mexico were first formed by native people walking from city to city. These roads – some paved – were used for conducting warfare, cultural interchange, and commerce. Later these same roads were trod by the heavy horses of the conquering Spaniards and the sandals of the missionaries. Still later, they were traveled by mestizo tradesmen and religious pilgrims. Today, these roads are known throughout Mexico as caminos reales, meaning “royal” or “official roads,” sometimes translated as “the king’s highways.”

In Morelos, just as throughout the rest of Mexico, Augustinian, Franciscan, and Dominican missionaries built their convents near existing native populations to facilitate their conversion to Christianity. After the network of convents shifted into power, the routes that connected them were used for centuries by the friars and people, alike. Now, with the relatively recent construction of modern highways, the routes are being forgotten.

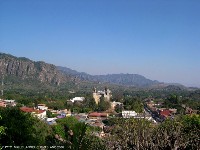

But something special is happening in Morelos because it is home to part of the last surviving network of convents in Mexico. In 1994, 14 sixteenth century convents (11 in Morelos and 3 in Puebla) were listed as World Heritage sites by UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). This did a lot to ensure the survival of these convents as important cultural and architectural resources, but some essence of the network that makes them special as a whole is still being lost. This is because visitors reach the convents by car, traveling on highways that don’t follow the original routes.

Miguel Ángel Cuevas Olascoaga, a 35 year old resident of Morelos, aims to revive the network itself by re-opening the routes that tie it together for the people of Morelos and the world to enjoy. Cuevas has his bachelor’s degree in architecture, his master’s in conservation of cultural heritage monuments, and is currently pursuing his doctorate in architecture and urban design. His thesis in progress is on the design of cultural tourism routes. He hopes that twice a year, groups of people will be able to walk the king’s highways from the slopes of Popocatepetl through northern Morelos, visiting the World Heritage convents as they go.

Of course, before he can do this, Cuevas has to know exactly where these royal roads are. As part of his research, he and a researcher from INAH (the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, The National Institute of Anthropology and History) spent 9 days walking 242 kilometers (just over 150 miles), visiting all 14 convents and getting lost only twice. They took with them a compass, GPS, video camera, water, and maps. There are few places to stay along the route so, like the original pilgrims, they asked permission to sleep in the huerto (garden out back of the convent) or in the portal de los peregrinos (a covered area connected to the chapel, usually to the right of the main entrance, built to shelter pilgrims).

As they went, they identified the road construction to confirm that they had found the actual route. The original roads took three forms. The largest was the calzada, which was as wide as a modern road (8 to 10 meters). Calzadas were generally unpaved, but were occasionally paved with stones at the entrance of certain towns. They were used for the transport of people walking, domesticated animals, men on horseback, carts pulled by animals, and cattle. The middle sized roads are called caminos and were 3 or 4 meters wide and used by people walking or those on horseback. Less than half of these were paved with stones, with the pavement extending no farther than 10 kilometers from the town center. Finally, there were veredas, which were no wider than a meter and used by people on foot. Cuevas and his partner identified the paving techniques, looking for those that originated in the 16th century.

Despite the fact that people rarely use these routes to go from town to town anymore, they are still known as the royal roads. To get a general idea of where to start looking, they often asked the older locals, “¿Cuál es el camino real que llega a …?” (“Which is the king’s highway to…?”) The older people know the roads from the days before cars when they used to travel on horseback, transport their goods using mules, or walk to the next town.

In fact, every city of Mexico has its king’s highways, hidden within its fabric. And every city of Mexico has its old men who remember these roads and can tell their stories. These royal roads have been built on, around, and in many cases, re-built for modern traffic, but they are still there because people still travel them, whether they realize it or not. Grandfathers still remember the days when people hired arrieros (muleteers) with their mules or donkeys to carry their harvested corn, beans, or grains from the field to market. Arrieros traveled the royal roads back and forth from town to town, kicking up dust in the dry season and getting coated in mud during the rainy season.

Imagine a Mexican town you know well. Where might the king’s highway have started or ended? Imagine the men outside of town, resting near the road or playing cards or having cock fights in the shade of a tree. Imagine all the stories of adventures and misadventures, the busy daytime traffic, shuffling and clopping along, hurrying at dusk to get into a safe place. Imagine the lonely road at night, a worried family bringing a sick person to the biggest town in the region, with no flashlights – guided by the moon.

Grandpas still tell stories about events along the royal roads. They know who fought whom at the designating fighting spot or where the devil or La Llorona (the ghost of a crying woman) habitually appeared to drunks who traveled too often at night. The trees, rocks, and curves in the road are the big landmarks of the past, and today we pass by and know so little of them. Since the only way a road can die is if people stop traveling it, Cuevas’ project will help to keep a small portion of these king’s highways alive.

Cuevas’ doctorate thesis won’t tell stories of cock fights, and devil sightings, but it hopefully will help to open the royal roads connecting the World Heritage sites to visitors. The visitors will have to imagine the old days themselves or stop to ask a grandpa what he remembers. Cuevas’ proposal is that twice a year, for two weeks each time, visitors would be able walk the caminos reales as part of a truly Mexican cultural experience.

He hopes that these road openings will be during Holy Week and in November in the days surrounding the Day of the Dead. Visitors will enjoy observing the preparations, festivals, and completion of these special celebrations with their accompanying sights, sounds, and smells, as well as the sun, views, and clean air of the countryside. He likes the idea that these holidays strike right at the heart of Morelos’ complex history. The celebrations include elements from pre-Hispanic as well as Catholic traditions and are rooted in the very land that the route crosses.

He personally enjoys the contrast of the sights and smells of the countryside with those of small towns, particularly surrounding the Day of the Dead. As you enter a town you leave behind the smells of marigolds and other flowers, cattle or sheep, and grasses and begin to hear people’s voices, smell the foods of the offerings, especially the bread, smell the copal burning as incense, etc.

He believes that the route should be enjoyed in groups, which can be organized with guides, first aid, and security support. You can attempt the route alone, but for that must have a map and compass as well as be able to speak Spanish and be prepared to handle any threats to your personal safety. If you would like to join a group and walk all or part of Morelos’s royal roads, seeing the towns and countryside, learning about the architecture of the convents, and appreciating the local celebrations, Cuevas will be organizing some pilot walks during 2008 to test the feasibility of his idea. You must be in reasonable condition for walking and preferably be able to speak at least a little Spanish. You can contact him at the doctorate department of Architecture at the state university of Morelos. (postgrado de la facultad de arquitectura de la UAEM, email: [email protected]).

So what happened? Did these organizized groups ever materialize in those kings roads you talked pd about? Can they be seen firstly in 2024?