You are reading part 1 of Foreign artists in Mexico from the Revolution to the present.

- Part 2 (coming shortly) – Foreign artists influence Mexican culture and vice versa

In 1863, French writer and critic Charles Baudelaire did not consider an artist to be “worldly” but rather like a “serf to the soil,” dedicated to the area in which he lived. He could not have imaged what life would be like for artists in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Coming to Mexico

For Mexicans the concept of “immigration” has more to do with going north to the US than with considering Mexico a receiving country for migrants. However, for certain types of people, Mexico seems to be the perfect fit. And despite the relatively low numbers, foreigners have had a significant impact.

Through the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, most artists have come to Mexico out of choice rather than desperation. The main exception to this rule is those who came during the 1930s and 1940s from war-torn Europe.

Over the past century, Americans have dominated numerically, but not just because of geographic proximity. Mexico has had a place in the US psyche as a place of escape, especially since the late nineteenth century. With the concept of “run for the border,” Americans, artists or not,maintain a fantasy of getting away from it all.

But others have also found that Mexico offers them freedom. While not their initial reason for coming, artists from Canada, Europe and Asia agree that they have more artistic and personal freedom in Mexico than in their home countries. Overall, Mexico is less regulated than counties in the developed world, with rules and laws often not enforced. Time management is not a major concern either, taking daily pressures off artists. Akio Hanafuji of Japan, Chiang Pei of Taiwan and Kiki Suarez of Germany also praise Mexico’s openness to alternate career paths, welcoming artists based on talent as opposed to their home countries’ strict preference for credentials and seniority.

The other major freedom for artists in Mexico is economic. Art today is a global business, and many of these artists still earn dollars, Euros, and yen. Lower costs of living and favorable exchange rates mean that artists can focus less on the business end and even produce full-time in a way that is not possible back home. This advantage has increased over the past 20 years with advances in communication and transport technologies. Artists are even moving out into other areas of the country such as Guanajuato, Chiapas, Veracruz, and Oaxaca instead of concentrating in relatively expensive Mexico City.

Then, of course, there is Mexico’s rich culture. There is no denying the country’s exotic appeal for those from the non-Spanish speaking world. For those from Latin America, the draw is Mexico’s “big brother” status, with Mexico’s prominence in both art, archeology and folk culture so successfully maintained through its gargantuan tourism industry. Over the past century, it has brought artists such as Guatemalans Carlos Mérida and Rina Lazo, Dominican América Rodríguez, Cuban José Bedia, Chilean Carlos Arias and Colombian Musalán Guzmán, all developing as artists with a healthy respect for Mexico’s heritage.

But artists from all geographical regions spoke of something special about being in Mexico for inspiring creative work… a kind of “energy” that exists here. For established artists, that energy inspires them to take their work in different directions, from something simple to changes in their color palettes, to radical changes in style and themes. One example is those American and European artists of the conceptualism period (roughly late 1980s to the 2000s) like Michael Tracy, Melanie Smith, and Francis Alÿs, who came to Mexico to experiment and even develop their reputations as artists. Mary Jane Miller found that she could pursue Byzantine iconography with a feminist twist without judgement. In more than a few cases, non-artists found that they did indeed have the talent and interest. The most successful of these is sculptor Naomi Siegman, who came to Mexico as a housewife in the mid-century. Karolina Pasikonik is a Polish anthropologist turned media artist and German-born photographer Crista Cowrie came as a teen looking for adventure.

One interesting note is that resident artists are almost exclusively attracted to central and southern Mexico, rather than the “cowboy” culture of the north. This is despite the existence, starting in the 1990s, of “border art,” politically inspired work done on or near Mexico’s northern border, often with messages aimed towards US immigration policy. But rather than be inspired to live here, foreign artists simply come, do their project and move on.

What is it to be a foreign artist?

To be an artist today is to be part of a global community. Living and working in foreign country often has a profound impact on the artist and the work they produce. But it is important to define what it means to be a “foreign” artist in a “foreign” country.

My book project, tentatively titled “100 years of foreign artists in Mexico: 1920- 2020,” is focused on artists born outside Mexico but living in the country at least 2 years. One important finding was that “foreign” had much more to do with where you grew up and obtained your values rather than where you were born. For example, artists like Pedro Friedeberg, who come to Mexico as infants, are really not “foreign.” Their identity and value bases are Mexican.

What is important is that the artist in question must experience a culture clash, a clash in values and identity. In this sense, the two-year requirement worked out well, as it was the minimum needed to get over the “honeymoon phase” and deal with the sometimes uncomfortable questions of identity and acculturation.

Such questions affect all foreigners living in new countries, but it generally does not affect their work like it does an artist. Artists work from their personal feelings, extrapolating them onto a wider human reality. So, desires to share their new experiences in Mexico, as well as questions about who they really are, appear in artists’ work. For example, in the early part of the 20th century, many artists came looking to apprentice under Mexico’s famous maestros. Some artists still come looking to “paint like a Mexican,” but very few find that they can. Japanese-born Yuko Kawahara states that however much she tried to capture the essence of Mexican folk art in her work, her paintings are still “Japanese” especially in the use of color. She has come to accept that she cannot be a “Mexican painter,” and that she will always depict Mexico how she sees it.

That foreign perspective is a double-edged sword. One the one hand, foreigners are free from local prejudices and can be less-conventional, perhaps even work in ways that native born Mexicans cannot. But on the other hand, they cannot know this culture to the same depth, leading to real dangers in stereotyping, creating simplistic images often focusing on Mexico’s more exotic elements. The more years the artists spend here, the less it seems to be a problem.

But perhaps more important source of artistic inspiration is the acculturation process itself. Many artists talked about “superficial” changes to their work, in particular how their color palettes modified. These include Lao Gabriella from Argentina and Eddie Clausen of Germany, whose colors brightened, and América Rodríguez of the Dominican Republic who found life in Mexico City toning her colors down. Some still become fascinated with the imagery they find themselves surrounded with. These include Akio Hanafuji’s dedication to depicting the Chiapas that he looks at with Japanese eyes. They also include the many artists, including Susan Santiago and Karen Lee Dunn, in San Miguel de Allende, Ajijic/Chapala and Puerto Vallarta who dedicate much of their time to depicting the towns they fell in love with. Those who came into their own in the 1990s and later may focus on materials and urban vibe, focusing on Mexico City. They use materials and images from the city, but their work is usually about globalized and personal topics that interested them before. The “Mexican element” in their work is usually found objects and materials, and if they do represent something about the country’s capital, it is as an example of the modern world. The most famous artists of this type include Melanie Smith, Francis Alÿs and Thomas Glassford. They also include Richard Moszka, one of the few from the 1990s who still lives in the country full time and newcomer Micheal Swank, who tears apart and rearranges old advertising posters to create works related to the challenges of his personal life.

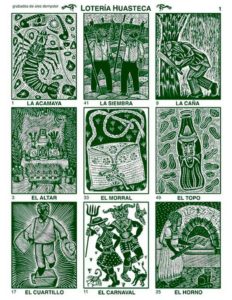

In some cases, a shift in identity leads to a commitment to Mexico socially. This was particularly true in the early part of the twentieth century, with artists such as Mariana Yampolsky, Pablo O’Higgins and the Greenwood sisters becoming involved in the muralism movement and the social causes it supported. But it also includes more recent work. American Judy Wray retired to Tepoztlán, Morelos, and immediately started working to organize her neighbors to create murals to increase the livability of her neighborhood. Natasha Moraga is doing something similar in Puerto Vallarta, specializing in broken tile work (trencadis or pique assiette) to reclaim run-down areas. Canadian Alec Dempster focuses on graphic work, often to promote traditional huapango music, which he also plays.

Almost all the interviewed artists acknowledge the Mexico change who they are and how they work and still does even if they could not explain it. German Kiki Suarez (legal name Irene Elisabeth Oberstenfeld) has a background in psychotherapy, which allows her to talk about it. She states that living in Chiapas broke down her inner structure the result of the culmination of subtle changes over time. Living in a culture with a whole other set of assumptions about how humans (should) think and act, and the need to adapt to it, she says is “… like dying and being reborn.”

With only a few exceptions, those who live in Mexico are a self-selected bunch, who go through the acculturation process because they want to and/or feel they get something from it. Exceptions include Leonora Carrington, who was a refugee from World War II, who kept her personal life and work almost entirely isolated in her home in the expat enclave of Colonia Roma, Mexico City. Until her death, she focused on the fantasy world she constructed in her English youth. Indeed, most foreigners who choose to keep Mexican influence out of their work (and even life) often are found in large expat communities… right alongside those who are happy to include such influences.

On the other extreme are those who “go native,” those who reject everything from their home culture in favor of the Mexican. The best examples of this come from the muralism period such as Canadian Arnold Belkin, the aforementioned O’Higgins and Yampolsky who tried their darnedest to leave all of their native identity behind. I did not find more recent examples of such, likely because back in their day, the ideology of the Mexico they loved was nationalistic. Today, the prevailing ideologies among artists are globalist.

Of course, most artists navigate a broad sea in-between. But those who stay at least two years, find that their Mexican experience continues to have at least some influence on their later work. Those who make it to the five-year mark almost never leave or cannot imagine leaving. The few that did leave after such a long time had familial reasons, and always left with regret.

- Part 2 (coming shortly) – Foreign artists influence Mexican culture and vice versa