You are reading part 2 of Foreign artists in Mexico from the Revolution to the present.

Mexico’s art history and foreign artists

Mexico’s art history of the past 100 years has basically been a shift to internationalism, with some hiccups during times of national strife. The different movements did make a difference in how and how much the Mexican art scene affected foreign resident artists.

From the 1920s to about the 1940s, Mexican art, especially its mural painting and graphics made the country a cultural powerhouse in the world. Foreign artists that came here during this time were not looking to do their own thing, but to integrate themselves somehow in the movement that captured their imagination. However, these artists were not always welcomed. Major commissions in Mexico City were all but closed to them until the 1950s. Diego Rivera was somewhat open to foreign assistants, but José Clemente Orozco did not think they were good enough. Foreign muralists found themselves looking for commissions, often with little to no pay in the “provinces” places such as Taxco and Morelia. This would change by the 1950s as muralism waned.

For those foreign artists wanting to pursue Surrealism or other tendencies in those early decades, the marginalization was even worse. Despite having a “surrealist” reputation today, the truth is that almost all of Mexico’s notable Surrealists were foreigners, often women and had little presence in Mexico’s art markets until the 1950s.

Change was inspired by the Spanish artists and writers who came to Mexico in the 1930s and 1940s, but the “Ruptura” (Breakaway) generation was a Mexican phenomenon. This generation chafed under the restrictions in imagery, politics, and techniques of muralism, which were reinforced by government policies. The Ruptura generation wanted to be free to explore more personal interests as well as and trends being developed outside of Mexico. This was quite controversial as government/politics and art were joined at the hip, leading to worries about Yankee Imperialism.

The Ruptura period runs roughly from the 1950s to 1970s (with important contributions before and after those decades). It created opportunity for foreign artists, who went from second-class creators to equals with their Mexican-born counterparts. The number of foreign-born notable artists skyrockets during this time period, producing art in various styles and themes. Foreign artists became prominent during this time include Roger Van Guten, Brian Nissen, Antonio Rodriguez Luna, Philip Bragar and Helen Bickham, who were accepted “Mexican artists” as they gained prominence.

There is a fall in direct foreign participation in two of the movements that followed – “Los Grupos” and Neomexicanismo. This is because both were highly tied to the sociopolitical situation of Mexico in the 1970s and 1980s. This period started off with the Tlatelolco Massacre in 1968, when scores or hundreds of protesting students and others were killed shortly before the start of Mexico City’s Olympic Games. Up until this point, the Mexican government still enjoyed relative support from its artistic and intellectual classes, but the massacre broke this. The first reaction was the formation of artist groups using with guerrilla art tactics in the streets, as ways to get around the government’s media monopoly. The rebellion morphed into Neomexicanismo, which scrutinized many of the political and cultural icons established in Mexico after the Revolution. Only a few foreign names become prominent in these circles such as American Carla Rippey and Polish performance artist Marcos Kurtcyz. One reason is that Mexico’s Constitution forbids foreign interference in domestic politics (of course ignored when the artists’ politics agrees with that of the government). Neomexicanismo’s questioning nature pretty much required artists to have grown up in the culture: in addition, the 1980s saw the start of identity politics, which probably dissuaded foreign artists from a movement inherently critical of Mexican culture.

With relative sociopolitical calm restored in the 1990s, foreigners became again prominent in alternative art scenes. (They had always remained a force in the more commercial art markets.) This time period is marked with the rise of conceptualism, installation and performance art (making Mexico a little behind the curve on this globally). Europeans and Americans found post-1985 earthquake Mexico City a perfect and cheap place to develop their work. Preceded by the likes of Michael Tracy and Jimmie Dunham, artists such as Melanie Smith, Francis Alÿs, and Thomas Glassford have become internationally famous giving Mexico City its current reputation as an artistic hub.

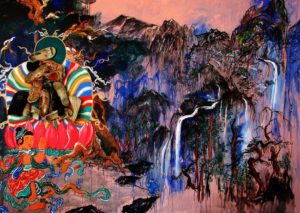

By far, most of the foreign artists to come to Mexico are from Europe and the USA, but it would be wise to mention that important contingents of Asians and Latin Americans have found their way here as well. Asian artists are dominated by those from Japan, mostly because this country was introduced to Mexican art in a major exhibit in the 1950s. There are multiple generations of Japanese (and other Asians) here, often fascinated by Mexico’s pre-Hispanic and folk cultures, which are both exotic and a tiny bit familiar at the same time. (One insisted to me that Quetzalcoatl is really a Chinese dragon.) Important artists from Asia in Mexico include Hiroyuki Okumura and Kiyoshi Takahashi of Japan, along with Eduardo Olbes of the Philippines. More recent arrivals include Japanese Miho Hagino, Shino Watabe, and Masafumi Hosumi, Chinese Lili Sun, Taiwanese Chiang Pei and Korean Minseok Chi.

As for Latin America and the Caribbean, the draw to Mexico has been more economic and cultural rather than political. The wave of Spanish political refugees in the 1930s set a precedent for those persecuted on the left, but coups in Argentina, Brazil and Chile did not send the numbers to Mexico that Franco’s Spain did. There are large numbers of Argentinian and Chileans in Mexico, but most have come for economic reasons after those turbulent decades. There was a short-lived phenomenon from Cuba in the late 1980s and very early 1990s. Not wanting to be in Cuba, but not liking the Cuban community in Miami, many artists found a happy medium in Mexico. Initially, Mexico welcomed these Cubans, but a change of administrations turned the tide against them.

It is interesting to note that Mexico’s relationship with its foreign artists is mixed. Almost all of the artists interviewed stated that there were both pros and cons. Those from the US and Europe recognized that there was some advantage from being from there with Europeans particularly sensitive to this. But artists also noted instances where there was even some discrimination or outright hostility against them, accused of taking opportunities away from native Mexicans. This was commented on by Francesca Dalla (especially in the movie special effects industry), Carla Rippey in Veracruz, and Peter Eversoll in Oaxaca. Only one, Dorit Weil from the Dominican Republic, complained about racism per se.

Oddly enough, few artists have explored, artistically or intellectually, what is means to be a foreigner in Mexico even though some noted interesting twists in their ethnic identity. For example, Luciano Spano stated he is considered dark-skinned in his native Italy, but here he is güero (white). Others, despite have significantly dark skin tones found it to be insignificant…that they are foreign is more important. The only artists I interviewed who did look into this were Carla Rippey and Francesca Dalla.

In essence, the process of adjusting to life in Mexico is the same for foreign artists as it for the rest of us. The fascinating difference is that it can, and very often does, have a direct impact on the work the artist produces. Such research of artists’ work over time here is important because it gives insight to how long timers in Mexico acclimate and meld into the country’s social fabric. Mexico’s reactions to such artists also gives insights into this culture as well. There is certainly no reason to believe that Mexico will lose is allure anytime soon.

Leigh Thelmadatter;s e mail, non facebook?

Apologies; you found a glitch in our system, now fixed! Click here to email Leigh.