In 1916, the Amparo Mining Company had the most successful silver mines in Jalisco and was making money hand over fist. Although it was located pretty much in the middle of nowhere, 65 kilometers due west of Guadalajara near the town of Etzatlan, rumors abound that a bustling community of some 6,000 souls once lived there, enjoying such luxuries as two supermarkets, a cinema, a dance hall and their own classical music orchestra. This community, it was said, consisted of Americans, British, Mexicans and lots of Germans.

All that is what the rumors say, but when I tried to dig up some hard facts about Amparo, I discovered a curiously different picture of life at the mining camp. “There’s a monograph on the history of the old mine,” I was told by archeologist Phil Weigand who lived in Etzatlan for years, “for sale in the convent book store.”

After three trips to Etzatlan to to get that monograph, I discovered it had only a few lines about the mine. They were anything but laudatory:

The miners worked their long, miserable, heavy days under brutal conditions,” said Maria de la Luz Correa. I got the distinct impression that the riches flowing from the mine had only flowed into the pockets of the owner, who it seems, was American, not British. I also found out that there were only about 500 some miners at Amparo, not 6000. As for the two supermarkets, it was claimed that their primary function had been to enslave the miners, offering them luxuries and expensive entertainment on credit until they were hopelessly in debt.

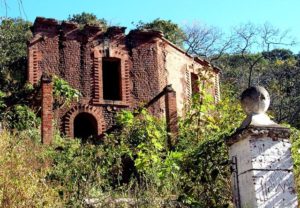

The miners are long gone from the Amparo Mine, but an impressive ghost town still remains and it’s not a difficult place to visit. Just drive south out of Etzatlan for about 16 kilometers and you’ll find the sleepy rancho of Amparo, surrounded by once elegant buildings now swathed in vines and bushes. “This was the bachelors’ dormitory,” local people told me. “That was one of the stores and this was where the miners received their wages.”

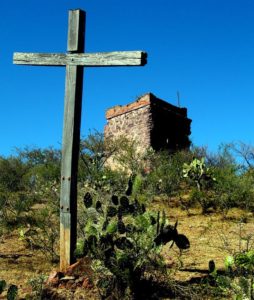

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing to a lonely tower atop a steep hill. “We call that El Faro, the Lighthouse,” I was told. “Actually, it was a watchtower built for driving away bandidos.” Once I saw the outside of this tower, pockmarked with bullets, I gained a new respect for those people who worked at this remote outpost — cinema or no cinema.

More ruins can be found about two kilometers south of Amparo at Las Jimenez, where electricity from high tension wires was transformed into useable voltage for the mine’s heavy machinery. Here I found the most beautiful building of all, several stories high. I was told the transformers were housed here, but the building looks too elegant for such a lowly purpose. Besides, transformers normally sit outdoors because they give off heat.

The miners at Amparo, led by famed Mexican Marxist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, joined a Jalisco-wide union in 1926 and made demands for better salaries and working conditions to the company, which chose to shut down the mine rather than capitulate. This mine produced 138,597 kilograms of silver between 1924 and 1931, plus impressive quantities of gold, lead and copper. It was still productive at the time it was shut down and would no doubt have been reopened later if President Echeverria had not (I was told) “stolen all the machinery and workings, causing the mine to be flooded.”

Recently, a friend of mine, mining geologist Justus Mohl, brought me a treasure. Somehow he had managed to find a copy of the memoirs of Salvador Landeros, a mining engineer who grew up at Amparo and eventually became General Manager of all the mining operations. This is a spiral-bound collection of 217 typed pages, including photos, maps and diagrams, dated August 3, 1998. Landeros paints quite a different picture than Maria de la Luz, of life at Amparo. Below are a few selected anecdotes that give us a feeling for what life was like in that remote mining town.

The Memoirs of Salavador Landeros

I was born in what was then called the Villa of Etzatlán in the state of Jalisco on the 31st of December of 1905. At the tender age of three months, I went to live in a remote place called Amparo where my mother had been hired to wet-nurse Fany, the newly born daughter of Mr. Santiago Howard, Manager of the Amparo Mining Company. And that’s where I grew up.

One of the people from my childhood I could never forget was a man with only one leg whom everybody called No Ambition (Poca Lucha). This man couldn’t work, but he had a special talent: he knew by heart all the stories of the Thousand and One Nights. We children all loved to get together with him at night to listen to his stories. Sometimes the grown-ups would come join us kids and everyone would give ten or fifteen centavos to our fascinating story-teller. And that’s how I passed my time before I reached school age, listening to those stories and playing. It was a peaceful time.

I fell in love with music at a tender age. Every time I heard music playing near the main office, I would go listen. The waltzes from that period were so exquisite I felt I was in heaven and when a string quintet would play them at sunrise, why, even the dogs stopped barking and perked up their ears to listen attentively.

It was the period of Romanticism, which ended in the 1940s. I would say that never in my long life have I heard more beautiful pieces. Eventually, I studied violin and in the orchestra I played many of those old waltzes and much more, including classical music… and I think I was not bad.

When I finished fifth grade at school, we were told, “That’s it. That’s all we do at Amparo.” However, our teacher, Miss Rosario Rentería, had recently come to Amparo from Guadalajara and asked the authorities for permission to add a sixth year, since there were eight of us in the class and we all had good marks. So, I completed sixth grade, attending school in the morning and studying music in the afternoon. No more children’s games!

Once I completed sixth grade, it marked the end of my career of studies. I couldn’t apply to a college in Guadalajara because my mother didn’t have enough money and besides, in the time of Porfirio Díaz, poor kids could not go to a college and mix with the rich, the children of hacienda owners.

From 1918 to 1928 was the period of the mine’s bonanza. It was a sort of paradise on earth. Because overland transportation was so poor, we had everything at El Amparo. The company store carried all kinds of meat and vegetables, clothing, liquor, shoes and even freshly baked bread. And nothing was expensive. A family of eight could live for a week on 15 pesos.

Of course, on Saturdays the miners wanted to do something different after working all week under the ground, so there would be dances in three or four houses at the same time. At Amparo there were always more than enough musicians to go around. We had a real symphony orchestra with 36 elements and it was just as good as the Guadalajara Symphonic of those days. In addition, we had two bands that played popular music and there was even an opera house.

On a Sunday, after eating, there were games. One of them was called Little Jars (Los Cantaritos). We would have about 50 tiny baked-clay pots made at a time. To play the game, we would form a big circle and each person had a cantarito. The idea was to throw yours to someone else who had to catch it without breaking it. Finally, there would be only one jar left and everybody had to be very careful because if it broke, the person who should have caught it was obliged to pay for the musicians and another set of cantaritos for the next game. Instead of getting drunk Sunday evenings, we used to play games like this until it was finally time to go to the cinema. And from there it was off to bed because a lot of the men had to get up early the next morning to work.

The Treacherous Tramway

We have an old saying: La confianza mata al hombre (Taking things for granted will kill you) and I have a story to back that up.

When mining was at its peak at Amparo, we had an aerial tramway which transported the raw ore down to Las Jiménez in big containers suspended from steel cables strung between four towers. To avoid accidents, riding in the ore buckets was forbidden, but there were always a few characters willing to take a chance. Now, on various occasions, the electricity would go off, but usually for less than five minutes. If the men running the tramway were going to cut off the power for a longer time, they would send word up and down the system by telephone, warning people not to ride in the containers.

Of course — even though it was prohibited — it was mighty convenient to get a ride uphill from Jiménez to Amparo and even people not working for the company used to take advantage. One of these outsiders was doing exactly that one day when the bucket he was riding in suddenly came to a halt 15 meters from the tallest tower. Now, by chance, there was a deep arroyo right at the foot of that tower, so the distance down to the ground was about 40 meters. Well, this fellow was sitting in the container, hanging in the air and he waited a long time and nothing happened. And he waited some more — and some more. And finally he just had to get down from that ore bucket and he looked at that distance, only fifteen meters, and must have thought it would be easy to get to the tower just by holding on to the thick cable with his hands and walking along the thin cable below it with his feet. So he went for it and got about six meters when suddenly the power came back on and the containers started moving. Well, the very bucket he had been in came straight at him and cut his hands right off and he gave a shout which was heard by a passerby who saw him fall to his death. When they found his broken body at the bottom of the arroyo, they discovered he wasn’t even a miner. The poor guy was living all along in Las Jiménez and no one had any idea where he had been going or why he had climbed into that container.

The Purloined Ingot

The silver produced at Amparo was melted down into ingots weighing 35 kilos each, which were then transported to the bank of London in Mexico City. One day a policeman was watching over a pile of these silver bars outside the foundry, waiting for a truck to come pick them up. Well, the guard walked away for a moment and some wise guy who had been watching ran up, grabbed a bar and threw it down into a deep canyon just next to the building.

When the truck arrived, they counted the bars as they loaded them and found one missing. Well they all went crazy looking for that silver ingot and because there was no way to account for what had happened to it, they naturally blamed the guard and Antonio Leal, the head of Security, arrested him.

Now they were all set to send the guard to Etzatlán when along came a common laborer who said he had been walking in the arroyo and had come upon a little house and just inside the door he had spotted something white and shiny lying on a brick.

Antonio Leal — with his entire Police Force — went straight to the house in question and sure enough, there was the missing bar of silver. Antonio then began hunting high and low for the owner of the house and finally found him planting corn. So they arrested him and took him to the office where Antonio Leal was all set to hang him from a pole.

At this moment, however, one of the doctors came along and asked what had happened. After hearing the whole story, he declared that Antonio Leal had no legal right to execute anyone and how could the accused have stolen the ingot without being seen. “And where did you find that ingot hidden?” he asked.

“We could see it because the door was open,” someone said.

“No,” said someone else. “It’s a shack and has no door at all.”

“OK,” said the doctor. “Bring the man here and let me talk to him alone.” Then he said to the man. “Alright, how did you steal that silver bar?”

And the man said, “Sir, I didn’t steal no silver bar. I just found that heavy thing down in the arroyo when I was looking for kindling wood and it looked awfully pretty, so I brought it home and put it on top of a brick to make a chair, ’cause I don’t have anything to sit on in my little shack.”

By now Don Guillermo Howard, the head man at Las Jiménez, had arrived. “This man is telling the truth,” said the doctor to Don Guillermo. “If he had known what he had in his possession, he wouldn’t be here now.”

“You’re right,” replied Don Guillermo. “We can’t blame him for anything. Look, not even the President of Mexico has had the privilege of resting his butt on an ingot of pure silver, as this man has so innocently done. He is guilty of nothing.”

He sent the man home but the poor fellow was so frightened, he simply vanished and was never seen around Amparo again.

The Fall of the Amparo Empire

(Thanks to Justus Mohl for this summary of Amparo’s last years)

If you visit the ghost town of El Amparo nowadays, you may wonder what happened to all that luxury in which Salvaderos Landeros grew up.

During the revolution, the mining management had to stay in Guadalajara for a while, but when it was all over, there were ten years of bonanza, from 1918-1928, with many festivities and dances and different ensembles. The Howard management brought in good teachers for the school and the children got all the needed materials free. Football and basketball teams were organized and the company always paid the expenses for competitions in Etzatlán or even in Guadalajara.

In 1926, nearby mines like, La Yesca, El Favor, 5 Minas and San Pedro Analco, were shut down due to political disorder. The striking miners, about 500, came to El Amparo telling them that everybody should join them to demand better salaries and better working conditions. About 600 unemployed striking miners went to see the governor of Jalisco, and finally, 5 months later, the president of Mexico, Plutarco Elías Calles signed an agreement forming a “cooperative” to administrate the El Amparo mine.

When in November, 1926 the peaceful workers from El Amparo became disturbed, the main accountant Adolfo Hoepfner told the Howard management to leave, thinking he could handle the situation, but some weeks later his own workers fatally attacked him with knives and machetes in order to distribute the ore and the bullion among the striking workers.

Finally, when the Howards had to accept the workers’ demand and abandon everything, it was Landeros who survived in the deserted town of El Amparo and, years later, it was Landeros who tried to put the mine back into production.

This worked for a while. Money from the ore was distributed among the workers, and initially the earnings grew, since there were no large salaries to be paid to management and nobody cared about searching for new ore reserves or spending big money on maintenance and equipment.

During that time everybody was told that the foreign management had been abusing the workers to become rich themselves. The good treatment extended to the workers, as well as the facilities, benefits and the warm personal relations between workers and staff, were all soon forgotten.

During a period of two years, until 1939, the new organization, called La Cooperativa Minera, was productive, but when they had to pay the pending electricity bills, the miners were asked to deduct it from their income. Other problems then developed, due to corruption on the part of managers (who were elected by the workers and spent their time playing with dominoes and girls in a Guadalajara hotel) and laziness on the part of the workers. In the end, there was no money and when the miners realized that nobody was ever going to pay them, they carried away everything they could, leaving behind only the ruins you can appreciate today in El Amparo.

Was Amparo a paradise or a prison? We may never know the whole story, but let’s hope more documents like the memoirs of Salvador Landeros will eventually come to light. Meanwhile, today, it is said that several companies owned or financed by Carlos Slim, richest man in the world, have their eye on these long-abandoned mines. It seems the history of El Amparo is not quite over.

That’s the Great History of El Amparo! Once upon a time it was one of the beautiful buildings in Mexico but now overgrown with weeds. Keep sharing such historical content.

yes its beautiful i saw two pictures from there era now ruins the town over Etzatlan is wher i am from and the railroad tracks are still there