PART ONE: ORIGINS

“The mountain, she is not innocent….” Senor Reyes’ voice trailed off as his words hung in the dry air of the climber’s hostel in Tlachichuca. John and I toned down our giddy anticipation and shifted uncomfortably in the sudden gravity of the moment. Reyes was perfect, exactly the type of mountain man you expected to find at the end of the road in charge of a climbing hostel. His intense brown eyes augered straight through us, sizing up the two raggedy specimens in front of him as a worthy match for nearby Citlaltepetl, Mexico’s highest volcano.

We slumped in our chairs, both dusty and strung-out from spending the day jumping buses on rural routes all across Mexico. I suppose we did not inspire a ton of confidence in him. We had just arrived in the little town at the base of Citlaltepetl, known locally as El Pico de Orizaba, and were settling up with Reyes for lodging and jeep transport the next day to the trailhead. Reyes gave us the rundown on his operation and then sent us back to the rack room. As we secured our stuff for the night I wondered if we had passed his test. Did we appear worthy? How exactly do you say ‘helicopter rescue’ in Spanish? Once again I wondered if this was still a good idea.

PART TWO: GETTING THERE

Opting out on the Mexico City smog, from Denver we flew into the Caribbean port town of Vera Cruz. This would allow us, we reasoned, to enjoy a happy margarita on the beach after the climb. The day after we arrived was spent piecing together bus schedules from the coast up into the Cordillera de Anahuac and the tiny town of Tlachichuca. There were no direct buses to Tlachichuca, so the day was spent dragging our expedition duffels from bus to bus, heaving them in and out of various taxis, and struggling though many desperate conversations with bus personnel about times, schedules and routes. I had forgotten that climbing the volcano was actually only PART of the adventure.

Venturing across Mexico by local buses isn’t the easiest or safest way to go, but it does expose you to the amazing people and reality of small town life in Latin America. Along the way, the geography changed from the humid coastal lowlands and Pacific oil palms to the dry and rugged cordillera. When we got to the Reyes compound in Tlachichuca, it was almost 9 pm and we were grimy from a day spent wading through Mexico’s rural bus system. We settled with Reyes at the office of the hostel, where he uttered his famous line, and were set up with a few nights lodging and transport up and back from the volcano.

Other people at the Reyes had just come back from the mountain and sat around on couches in front of a pot-bellied stove staring at the wall across the room. They were exhausted and sunburned, their faces all red and windblown. A few quick conversations revealed that only about half the group made the summit in spite of the good weather. These also revealed that three Russians had died on Orizaba just the week before in a fall on the glacier. There was the scared story of one climber who got to 17,000 feet and blacked out, having to be helped down the mountain to the base of the glacier roped to another climber.

The ones who made it were rather upbeat about the whole thing, but everyone was so tired that little of this enthusiasm shone through. After dinner one of Reyes’ staff mountain guides held a fascinating slide show on climbs in South America and Nepal. But by the end of it half the people were fast asleep on the couches. We walked around the place briefly after hearing the stories, letting everything sink in.

Reyes runs a slick service out of Tlachichuca. He has an old soap factory that he has converted into a climbers’ hostel. It occupies half of a ‘chuca’ city block and has an enclosed wall that gives it the feel of a “compound.” Various implements of machinery adorn the main building such as the huge oak mixing vats for the lard and lye, belt-driven mixer paddles and the vast old furnace. In the main building there is a gear room and a few couches around a pot belly stove.

Everywhere people have posted flags, business cards and stickers from mountaineering clubs all over the world. A rack room upstairs holds 20 bunk beds with woolen blankets. In the courtyard outside there is a covered garage which houses three Dodge Power Wagons, huge and beefy 4WD vehicles for taking climbers up the road to Piedra Grande, the base camp for the summit attempts. 1952 and 1962 models, they have been fully restored and are probably the most reliable transport to Piedra Grande. We fell asleep that first night in the rack room listening to the snores of the other climbers. Outside, a nearly humorous cacophony of dogs, roosters, burros and car horns continued all night.

PART THREE: PIEDRA GRANDE

After breakfast we joined a second group from Colorado and packed ourselves and the gear into the back of one of the Power Wagons. The truck had the feel of an army personnel carrier. Two benches ran the length of the bed and metal bars were welded inside the cab to allow for desperate grabs to support oneself. John wisely rode shotgun up front.

The trip took close to two hours to cover 12 miles. Seven of us sat in back, gripping the metal bars and dodging packs and water bottles dislodged as the truck pitched and lurched through washouts in the roadbed. Dust clouds billowed in the screen windows. Several of us banged our heads on the metal ceiling and others were bordering on nausea by the time we reached 12,000 feet and the village of Hidalgo. We stopped here to pick up two additional climbers who had taken an extra day to acclimatize.

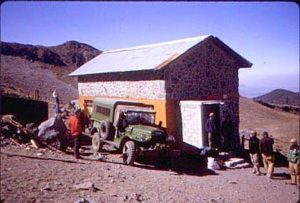

After a brief rest in a pine forest, we piled back in and continued up until breaking treeline at 13,000 feet. Thirty minutes later the road curved around an escarpment and we bumped our way up the rest of the dusty track to the huts at Piedra Grande, one of two main base camps on Orizaba.

The Octavio Alvarez hut sticks out among the profusion of large rocks scattered over a sloping plain, a stone structure with a corrugated metal roof. Three tiers of bunks, each about 15′ by 12′, are set inside. Two long tables serve as cooking platforms in front of windows that face up the valley towards Orizaba. The second hut only sleeps five and is set 100 yards uphill from the main one.

Garbage is strewn all around the huts and you must watch where you are stepping at all times. A rough outhouse sits 30 yards away from the main hut, but the privacy has been compromised by the fact that the door has been blown off. Most opt for a long ditch a few yards uphill from the outhouse, an angular gash in the dry soil filled with fluttering toilet paper and camp garbage.

Inside the big hut dust and dirt accumulate on everything. After sweeping off the cooking table with a filthy broom, clouds of dust filled the place and hung in the air until we forgot they were there. We were told to sleep with our heads out towards the door (and the activity) so the mice wouldn’t bother us as much. Mice? We grabbed the top deck in the big hut just as another group of tired and grimy climbers was moving out and eagerly chucking their packs into the Power Wagon to get out of Piedra Grande. We set ourselves up, chit-chatted with the other guys in our crew, and took a quick acclimatization hike up the valley in the general direction of the glacier.

Hiking in this altitude is ridiculous. Even with light packs we were wheezing as we trudged up the dusty trail that wound through the scree field up to the glacier. Learning the way up was good practice for us though, because when we were on the actual climb it will be at night and we would have to negotiate our way up this part with headlamps. Some terrain memory would definitely come in handy. Back at the hut we boiled some pasta for dinner and sliced off a 1/2 stick of butter into the mixture to lather it up a bit. We drank tea constantly, adding two heaping teaspoons of sugar to each cup to help our bodies absorption of the water.

In the course of doing our research on high altitude travel we came across several alarming facts. Evidently above 17,500 feet it is fairly common for the capillaries in the eye to burst. You know it is happening to you when you notice your vision getting all clouded up. There is no way to prevent it. Drinking water is one of the most important things about keeping yourself healthy at high altitudes. The dryness of the air and the increased breathing rates suck moisture right out of you. To prepare for this, we had sworn oaths to ‘pound’ water whenever possible and take a high altitude drug called Diamox. Being a diuretic, this means frequent bathroom trips. It also stifles the appetite and makes the fingers and face tingle as added-bonus side effects. These are the bizarre challenges of the climbing world.

The wind howled all night banging the metal roof against its wooden supports. The stars however were absolutely brilliant on my many piss breaks throughout the evening. The next thing I knew someone’s alarm went off at midnight and bodies and gear began moving around loudly in the hut.

PART FOUR: CITLALTEPETL

I lay in my bag and weighed, as every climber inevitably does, the attractiveness of staying put and leaving the climb for another day. I pondered my options: 1) stay safe and warm. 2) begin an 20 hour day dragging myself towards some objective thousands of feet above me in the frozen darkness. For the moment the confines of the sleeping bag were winning out. But then I remembered what another day at Piedra Grande would be like, and I suddenly found the motivation I needed.

Within a few minutes tea water was boiling. Others were getting suited up and the comforting hum of butane and whisper lite burners fought back that of the gusting wind outside. We repacked our packs for the fourth time, trying to determine the optimal mix of clothing and gear to fit the imminent tasks.

When the oatmeal was finished we threw everything into hanging bags and stuffed the cooled-off stove into my sleeping bag to keep it from curious eyes. We had all of our stuff on by 1:45 and exited the hut into a dark landscape dwarfed by a sky positively saturated with brilliant starlight.

We hiked at a brisk pace up into the scree slope, noting the bobbing headlamps of a group a half hour in front of us. The night held a stiff breeze. The first part of this hike we had done already so we knew what we were in for: steep, highly eroded slopes, dust clouds, few switchbacks and large loose rocks. In the dark it passed slowly and we marked our progress against the clumps of headlamps coming up below us from the huts.

By 3 am we had reached the tongue of the glacier and roped up. The next two hours we traversed back and forth across the gradually steepening ice, keeping a prominent rock outcropping to our left until coming out at a relatively flat section at the base of the glacier.

We regrouped and downed a liter of water, noting the ice chunks already floating in our nalgene bottles. John fumbled with putting new batteries in his headlamp, which had burned out on the first ice section coming up. Two other climbers were resting at this spot as well.

Nobody had a plan for proceeding up the glacier, so we fell into an impromptu meeting to discuss the matter. We’d seen the crater rim the day before from this spot, so it was fairly obvious where we were going. Basically it was straight up the hill, which at that time was visible only as the vast black area blotting out the amazingly bright field of stars above us. I attempted to communicate.

“Well, you pretty much just, like, go right up there.” With furrowed brows and nodding headlamps the group considered this. One of our friends pointed his ice axe up the hill.

“So just between those two rocks and then on up?”

“Uh, yep.”

“I see. Interesting.” It is tough to be eloquent standing on a glacier at 3 am in a freezing wind at 16,000 feet. Also, my mouth was partially frozen from drinking down large quantities of ice water. I shrugged. Everyone nodded in agreement without really deciding anything. We resecured the packs and tentatively began the slow hike up the ice. Were there better ways to get up this glacier? It was anyone’s guess.

John and I passed the other two within 20 minutes and I found myself leading the glacier without any real clue about a proper route up this thing. To the East we could see the lights of Vera Cruz and other smaller towns on the Caribbean coast. Above, the stars were so clear that they began obscuring the familiar constellations. Orion barely stood out against a field of innumerable twinkling diamonds.

We kept zig-zagging higher and higher into the darkness. For several hours our entire world consisted of nothing but the ice lit by the circle of our headlamps. I kept waiting for it to level off but the slope seemed to enjoy not leveling off and eventually I stopped hoping for it. At 17,500 feet it actually steepened and the sun finally came out at 7:30.

We were a few hundred yards below the Aguja del Hielo (ice needle marking the lower lip of the crater) and I started thinking for the first time we were actually going to make it. I hadn’t heard a word from John in over an hour, our communication limited to gentle pulls on the rope and hand signals. He seemed to be alright so I kept up the pace.

At the ice needle quite suddenly you find yourself at the rim of the crater, which drops about 400 feet and is close to a quarter mile across. The terrain change is startling. Where it was finally safe to stop for pictures we took a quick rest. Orizaba threw an incredible shadow to the West, laying down its dark pyramidal shape across 40 miles of the dry plateau.

I tracked my eyes from that spectacle and around the crater rim and noted a small rise with a bunch of metal crosses sticking out of the snow: The summit! It looked close. We kept going and soon popped over a rise and found a flat section where we took some more water and caught our breath before continuing. There is one 30′ section of the trail where the tread is only 18 inches wide. On one side it drops off into the crater. On the other side, the glacier ice drops off at a steep angle.

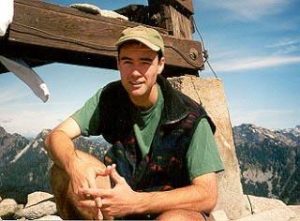

The next thing I realized I was stumbling the last few feet to those crosses and smacking the main one with my ice axe as I walked up to it. There was a lot of exhaustion and deadness in my reaction but there was also that undeniable adrenaline surge as you crest that last bit of earth standing between you and the sky. John clinked his axe on the cross as well and we congratulated each other.

We took our pictures and basked in the view, which included the two big volcanoes to the West and the Gulf of Mexico to the East. Two other groups soon gained the crosses. We took some final shots and began the descent after spending 15 minutes at 18,700 feet. The descent was a long and agonizing process peppered with rest breaks, picture taking and John and I trading insults about each others’ alpine mountaineering abilities.

We arrived at the hut at 1:30 pm and the Power Wagon was already there. We hurriedly packed up, gave all our extra food to the new set of climbers and piled once again into the back of the jeep for the dusty trip down the hill to Tlachichuca.

PART FIVE: EPILOGUE.

John and I huddled at a little plastic table drinking our beers as the wind and rain ruffled the awning overhead. I watched water torrents rush down the side of the street carrying small palm fronds and leaves away in the current. Whitecaps in the Gulf were just visible from the street corner restaurant through the sheets of rain. The wet coastal air was so thick it nearly gave us a buzz to take a deep breath. It was a slow Saturday night in Vera Cruz, a night that was not going to include our margaritas, lawn chairs or powdery sand between our toes like we had envisioned a week before. This was not a problem. After all, there were no burst capillaries, frostbitten feet or lost gear.

We drank cheap beers in a tired silence, considering contentedly the dangerous potential of this new hobby to lay waste to our next few years’ vacation days.

great adventure and summary. my friends and I, too, had experienced the thrill of the Mtns. and volcanoes in Mexico, and enjoyed the hospitality and transport of Senir Reyes…only four years before your ascent ( to the day). great memory relived thank you for your accurate descriptors and vivid recall. the night skies were incredible and I remember seeing Cassiopeia in her wonder….and the stone yert truly only housed 12, but it was the early start and glacier fields that hit home best. well written great retelling

Thanks for taking the time to comment; delighted that the article triggered some happy memories. Onward and upward . . . Editor