Thousands choose our mostly sunny country for retirement and live happily ever after. Some come only for emotional re-starts. Some hide here. Some swoop in and take what they want.

With a brutal drug war in full burn, with innocents being kidnapped and tortured, you wouldn’t expect a mere murder mystery with a bit of background treachery to last long in Mexico memory. But the intriguing story of Perry and Arthur March lingers. For several Lake Chapala residents, each anniversary triggers a quiver. Among tragic tales told in two languages, this one is as bad as it gets in the colorful history of Jalisco.

If you ask quietly, you can still find some who befriended Perry, the former Tennessee attorney. They had no clue that he had killed his first wife.

If you question the right sources, you can learn how others lost fortunes to his fraudulent schemes. One loser committed suicide. Another, desperate minus her resources, retreated north and humbly returned to work.

Leo Dietz was close to the fire. He had documents on his desk for an off-shore investment venture. Just sign here and here and receive double dividends. Of course it will be tax free.

A minute past the last moment, Leo decided it all sounded too good to be true. He wanted out. Perry was plenty miffed. Leo summoned heavy artillery, a university dean with powerful connections in Guadalajara. Perry backed away.

Leo never knew if he missed great riches or saved a bundle. Your guess is as good as mine.

Gayle Cancienne said she was bilked out of $200,000 and change. She was quoted as saying, “I hope Perry March burns in hell.”

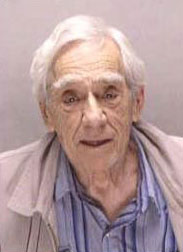

A few will admit they were totally shocked when Perry’s father, Arthur March, a longtime lakeside neighbor, breakfast at Salvador’s, regular at the American Legion, was found to be a dirty partner in crime. He eventually cut a deal and testified against his son. The Jewish community, rooted in loyalty, couldn’t believe its eyes and ears.

Arthur March died in prison. Perry March is still in and will stay awhile. A jury believed what Arthur said Perry said, that he struck and killed Janet March with a heavy wrench, in their Nashville home, during a divorce debate over his indiscretions. That was August 15, 1996.

While their two children slept soundly, Perry disposed of the body at a construction site. Cleanup involved discarding an oriental rug. His cover story was that they had argued and Janet had gone away for some time alone, a 12-day vacation to God knows where, and had left him a list of things to do around the house. Friends were puzzled. Janet’s parents were skeptical but waited for her return. The missing person report was generated two weeks later.

Lawrence and Carolyn Levine were deeply involved in their daughter’s marriage.

They had funded Perry’s law studies at Vanderbilt. He worked in the Levine law firm. They provided most of the money for the great stone house on four fine acres in an exclusive enclave. The showplace was deeded to Janet.

Investigators were suddenly everywhere, bumping into each other. They suspected Perry but had no proof. For weeks, he was cool, confident and not particularly concerned — until he heard that construction workers were having problems with an offensive odor. That was panic time.

Perry called Arthur in Ajijic. The father, a tough-talking 77-year-old curmudgeon, retired military pharmacist, rushed to the rescue. It was an ugly task but they retrieved remains and hauled their black plastic leaf bag, in Janet’s Volvo, in search of a better hiding place. Arthur chose a brush pile on a rural farm near Bowling Green, Kentucky. Perry couldn’t handle it. He took refuge in a motel room and watched TV.

In May 1999, Perry March, son and daughter moved to Mexico. Arthur knew everybody and all the ropes but Perry had his own tricks. He met another pretty mother, Carmen Rojas Solorio, at the Wednesday market in Ajijic. She and her husband sold the best muffins and cookies.

Soon and very soon, the Mexican man moved on and Perry March came closer, mixing and matching five kids.

In January 2000, a Tennessee court declared Janet March legally dead. Perry and Carmen were wed. When asked about her new man, Carmen said, “He’s a great husband. He’s sweet. He’s perfect for me.”

They added a child to the family. They opened a trendy restaurant. Perry rented second-floor space in a shopping center for his business affairs.

You might think a killer starting over would fly under the radar, maybe blend into the scenery. Not so Perry March. He was very involved during his six years at lakeside. Legal assistance. Investment consultant. He was into real estate development and property management. He could arrange insurance and security services. He chatted with clients and potential customers at the restaurant. He was smooth.

Several enterprises created dark shadows. There were a few open disputes. There were rumors of fraud, theft and other misdeeds. Most criticism was anonymous but there was a compact disc floating around that outlined alleged scams and estimated losses — a few million.

Perry March denied all and flourished. Arthur March said amen and stop by the house for a drink. Alleged victims were surprisingly quiet. The Mexican protest process is complex. Maybe there was fear of retaliation. Maybe silence was rooted in embarrassment. Maybe some “investments” were self-incriminating.

Back in Tennessee, the Levines were not so quiet. They kept their daughter’s case legally alive. They pursued custody of the grandchildren. They encouraged detectives to continue the search.

Janet was forever missing and tips and tidbits finally added up. In December 2004, the Davidson County district attorney persuaded a grand jury to indict Perry March on a second-degree murder charge. The indictment was sealed while Tennessee officials talked with Jalisco officials about deportation. Look around, guys, and see if Perry might have violated some immigration clause.

Sure enough, he had.

Alejandro Ochoa, gardener for the March family, was a wide-eyed witness when eight men in suits arrived at Media Luna Bistro & Café at 7:45 a.m. on August 3, 2005. They came in three SUVs and a maroon Mercury Grand Marquis. They interrupted Oaxaca coffee and pastry, took a very surprised Perry March into custody and hauled him away. Ochoa said it went down peacefully enough, no bullets, no blood.

More Mexican authorities were waiting at the Guadalajara airport. Documents, in triplicate, were signed and properly stamped. March was handed over to the FBI, destination Nashville. Perry was held without bail.

It just so happened that in the adjoining cell was Russell Nathaniel Farris, a klutzy career criminal awaiting trial on three counts of attempted murder.

After careful evaluation, March decided he was probably not guilty but just smart enough to be the perfect hit man when he got out of jail. Get rid of Janet’s pesky parents and Perry’s chances of beating the murder rap would improve.

The proposal to kill Lawrence and Carolyn Levine weighed heavy on Farris. He called his mother. She found Mr. Levine’s phone number in the book and warned him. He told police. Farris was signed up and wired as a secret agent. Hours of conversation with March were taped.

Arthur March rejoined the crime circle when Perry suggested Farris call him. Arthur provided details on how to do it. They discussed a silencer and thin surgical gloves and a happy landing after the hit. It was all on tape.

Farris was going to find sanctuary in Mexico. Perry had outlined a new business idea, express kidnapping, easy money. Perry said he had experience. Arthur was very reassuring. He was recorded as saying “Once you get to Mexico, you’ve got no problem.”

As Arthur told it, Lake Chapala was pure paradise: “The sky is blue, the beer is cold and the women are hot. What more do you need?”

Farris phoned Arthur March on October 27, 2005 to report that he would land in Guadalajara the next day, that his mission was accomplished, the Levines were erased.

Arthur watched for headline confirmation on CNN but went to the airport to meet his man — who was, of course, still in Nashville. Mexican police handcuffed the old warrior and presented him to FBI special agent Kenneth Sena.

The shocking developments did not noticeably shake Perry March. Deny, deny, deny. Arthur couldn’t take the heat. He spilled the entire story. Alas, when agents took him to Bowling Green to identify the disposal site, he couldn’t find it. The scene had changed but his details were so vivid, authorities had no doubts.

Neither did the jury. Perry was convicted on all charges, including stealing $23,000 from his father-in-law’s firm.

On August 17, 2006, a hard-nosed judge added up March’s sins and overwhelmed him with 56 years. Backlash struck Arthur. The judge rejected his plea deal of 18 months and imposed 60. It didn’t really matter. He died three months later at a federal medical center in Texas.

I do believe the March children are growing toward maturity in the tender, loving care of the grandparents.

There are those at lakeside, the burned and closet boosters, who still shake their heads at the mention of Perry and Arthur March. To some, they were a wicked combo, the worst ever. To others, they were old friends.

Leo Dietz, still intrigued by the March saga, thinks Perry is too slick for the feds to forever maintain a grip.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if he makes it back. Every time I sit down for lunch at Salvador’s, I look around to see if he has returned.”