Mescal, mescaline, mescal bean, mescal button; what are they? They are all intoxicants, which was what the word mescal meant in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Today mescal generally refers to a type of aguardiente – water with a bite, firewater, a liquor distilled from the agave, a relative of the century plant or maguey commonly used to make pulque, the drink of the gods of ancient Mexico. Mescal is a European contribution to the traditions of Mexico; before the conquest distillation was unknown in the New World.

Like its more sophisticated cousin tequila, mescal is distilled from a mash made of the crushed roasted hearts of the agave. The similarity, though, ends there. Tequila comes only from a limited region and must be made from the blue agave. Mescal is much more a “country” liquor, like the marcs, grappes and schlibowitzes of Europe. It is made from a variety of different agaves, using diverse regional methods.

Making mescal is a time honored traditional process. First of all, the spiked leaves of the agave are removed just before the plant is about to flower, when the sugar content is highest. The heart of the plant is pried from the ground, for only the hearts of the agaves are harvested. Then the piñas or pineapples – the hearts of the agave look rather like giant pineapples once their spiked leaves are removed – are brought in to the palenque (mescal production area) on the backs of burros or in sturdy but dilapidated pickups.

The piñas are then roasted in a pit oven – a large pit lined with rocks where a bonfire has been set – until the rocks are white-hot. Some people insist that the piñas must be broken up at this point, others prefer to roast them whole, nevertheless they are usually roasted at least overnight and preferably a full day in the pit until it cools off. The hearts of the agaves are then pulled out of the pit and crushed, mixed with water and left to ferment. Full fermentation of this mash may take three to five days. The mash is then distilled and the resulting liquid is known as mescal.

Mescal aged in barrels is called añejo. The longer mescal is aged in barrels the more mellow it becomes, like a fine cognac. Well-aged mescal can be quite expensive and a far cry from the rough country alcohol generally taken for mescal. Mescal also may be simply slaked in barrels for a day or so to mellow it. This type of mescal is called reposado. Mescal still warm just out of the still or alembique is incredibly potent and quality depends on many factors.

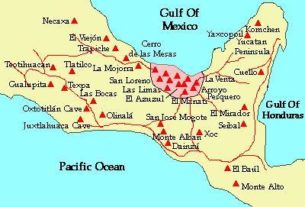

Some companies in Oaxaca and elsewhere may blend several different kinds of mescal for a particular flavor, but most mescals are from a single still at a single palenque, so they are more like single malt scotch in this sense. The best mescal by far still comes from small producers and individual stills. Men with their burros who harvest wild agaves just as they are about to flower, roast them, make them into mash and distil the mash, make the best mescal. Oaxaca is perhaps best known for its mescal, but mescal is made all over arid Mexico wherever agaves are found. Some of the finest single maker mescals come from Southern Puebla around Tepeji de Rodriguez, from Chilpancingo, Guererro, from Queretaro and Tamulipas.

The first time I tasted Mescal was in a mescal cocktail made by Doña Mecadia at the Posada la Sopresa in Mitla. We were there for a linguistic field school working on the devilishly tricky Mitla Zapotec language. After one particularly long session Doña Mecadia asked everyone if they would like a copita, a little cocktail. We went back to the kitchen with her and she measured out one glass of mescal reposado de naranja (mescal orange liquour), four glasses of mescal and the juice of two fresh key limes per person, then she added a tablespoon and a half of sugar per person and stirred the mixture up with a few large chunks of ice. She rubbed key limes around the edge of each glass and rolled them in coarse salt. Then she gave the mixture a quick stir and carefully poured it into each glass making certain that no ice slipped through. Alas, neither Doiña Mecadia nor the Posada La Sopresa remain in Mitla, but her mescal cocktail was by far the best I have ever had.

Doña Mecadia’s mescal cocktail was ambrosia and the real secret was her home made orange liqueur which I saw her making a couple of days later. She was picking a few of the oranges from the trees in the patio of the Sopresa. They were the old fashioned type of oranges, bitter oranges, or Seville type oranges, more suited for marmalade than for eating. She brought the oranges into the kitchen and washed them off, then cut them into quarters and put them into a large pan, skin and all, with one cup of sugar for two oranges and a cup of water. She brought the syrup to a boil and let it cool, then added a fifth of mescal for every two oranges. She said that the next day she would strain and bottle it because if she left it any longer it would become bitter. Doña Mecadia’s mescal cocktail can be made at home with any good orange liqueur but if you have access to Seville oranges or bitter oranges by all means make up a batch of Mescal reposado de naranja.

Mescal is basically a very versatile liquor in the kitchen it can be easily used in many preparations where a strong alcohol is called for. In most cases, flaming a dish just serves to burn off excess oils, thus the liquor has little effect on the final flavor of the dish. Mescal has a far lower sugar content than most liquors used in cooking such as cognac, brandy, rum or whiskey and can be used to advantage where you don’t like a sugary taste in a final dish. It is also great when paired with tart key limes or límones in sautéed chicken or fish dishes.

Mescal Chicken

In Tepeji de Rodriguez we were once served an exceptional chicken dish. When I asked how the chicken was made so tender our hosts replied ‘well, it’s the mescal.’ In Tepeji, where there is little refrigeration, the mescal serves not only to preserve the chicken but also to tenderize it. The first step in any recipe in Tepeji involving chicken is to catch the bird and pluck it. All chickens are ‘free range’ birds in Tepeji and some get enough exercise to be considered Olympic athletes, thanks to the local dogs, so they need some tenderizing.

- 1 Stewing chicken cut into eight serving pieces

- 4 oz. mescal

- 1 clove of garlic, crushed

- Salt and pepper

- Bay leaf

- A few sprigs each of thyme, oregano and parsley

- One small onion stuck with two cloves

- Water

- 1 lb. Mexican green tomatoes (tomatillos) coarsely chopped

- 1 lb. nopal cactus paddles roasted on the grill or sautéed and chopped

- 1 medium onion chopped

- 4 serrano chiles chopped

- 2 oz mescal

- Salt to taste

Salt and pepper the chicken pieces and place them in a glass dish with the crushed clove of garlic and the 4 ounces mescal.

Allow the chicken to marinate four hours or overnight in the refrigerator.

Place the chicken in a large pot, cover the chicken and its marinade with water, add the onion stuck with cloves. Tie the herbs into a bundle and add them. Bring the chicken to a boil and skim. Simmer for 20 minutes to one hour depending on the age of the bird.

In a large skillet, sauté in a scant tablespoon of vegetable oil, the onion, chiles and Mexican green tomatoes five minutes over a high flame. Add the chopped roasted nopal cactus and the rest of the mescal. Light the mescal and continue to sauté until the flames subside. Skim the fat from the chicken cooking liquid and add 3/4 cup of it to the mixture. Allow the liquid to reduce until it reaches the stage of a thin relish. Adjust the salt and add the chicken, turning each piece in the rather sparse sauce, and serve with rice.

Mescal Beef Medallions

Another specialty we were served in Mitla by Doña Mecadia was a mescal beefsteak. Traditional Mexican bisteces are thin cuts of very tough beef pounded paper thin to tenderize them, an operation that is absolutely necessary when beef comes from the scrawny cattle of the Sierra Mixe, which are definitely not corn fed. The flavor of such beef is quite strong and the pounded bisteces exude a considerable amount of juice that cooks down to a thick glaze, which is perfectly complemented by a strong liquor like mescal. Without the tasty but strong and stringy beef of Mitla there is a way to make superb medallions of beef fillet with a mescal sauce

This is not a country dish but a rather popular Mexico City product of the New Mexican cuisine. I have had several versions of this but prefer this simple way of preparing medallions of fillet mignon with no stock and no meat glaze.

- Eight four oz medallions of fillet

- 1 clove garlic, crushed

- 2 Tbs. Olive oil (not extra virgin, as it will burn)

- 1 Medium onion, chopped

- 2 Jalapeño chilies, seeded and chopped

- 1 1/2 C. tomatoes, peeled, seeded and chopped

- 1/4 tsp. thyme leaves and flowers

- 1/2 C mescal

- A few sprigs of Cilantro for garnishing

Rub the medallions with the crushed garlic and sauté in the oil at high heat searing each side then turning the heat down to medium until they reach the desired degree of doneness. Remove the medallions and keep them warm covered with aluminum foil. Meanwhile add the onion and chili to the pan the steaks were sautéed in. Cook for about a minute at high heat or until the onion is translucent. Add the mescal and allow it to flame, then add the tomatoes and thyme. Cook for five minutes at high heat to reduce the liquid. Season with salt and pepper. Pour the sauce over the medallions, garnish and serve.

Chacahua Shrimp

On the Costa Chica in Guerrero and Oaxaca, where shrimp are netted fresh in the dark lagoons, mescal is also used in a quick sauté that is a local specialty with shrimp fresh out of the water. The shrimp are left whole with head on and guests are allowed to peel their own shrimp from the huge steaming pile brought to the table. For more finicky guests the shrimp can be deveined and butterflied, but without the heads, the juice at the bottom of the pan which guests love to sop up with fresh tortillas is but a ghost of what it might be with fresh head-on shrimp. The trick to this dish is properly flavoring the oil.

- 6 cloves garlic finely chopped

- 4 whole dried red serrano chiles

- 2 lbs. head-on shrimp or 1 ½ lb. U15 shrimp shelled and butterflied

- 1/4 cup cooking oil (do not use olive oil, a light oil is best)

- 4 Oz. Mescal

- Juice of one límon

- 2 TBS chopped cilantro

- Salt and pepper to taste

Sauté the garlic in the oil over medium heat until it is uniformly golden brown. Add the chiles and allow them to take on a bit of color. This takes just a few seconds. Pour the oil with the chilies and garlic through a sieve. Reserve the chiles and garlic and return the oil to a large sauté pan. Add the shrimp and sauté until they are pink. Flame them with the mescal and return the garlic and chilies to the pan. Add the juice of the límon, the cilantro, salt and pepper, and serve.

Mescal Sauce for Seafood, Chicken or Pork

One final dipping sauce that is based on a British whiskey sauce will show the versatility of mescal in the kitchen. This sauce takes only a few minutes to make and is great with cold seafood, chicken or grilled pork.

- 1 Cup good mayonnaise

- 1 TBS Dijon mustard

- 1 TBS Cholula type Mexican bottled hot sauce

- Juice of one límon

- 2 oz Mescal

- 1 TBS chopped Cilantro (optional)

Beat mustard and hot sauce into the mayonnaise and squeeze the juice of the limon in. Very slowly stir in the mescal and add the Cilantro. Check the seasonings – some extra salt may be needed. Let the sauce stand fifteen minutes before serving.