Mexico in 1910 was a country in despair. Foreign domination had been replaced by the tyranny of President Porfirio Diaz. Two-thirds of the people lived in abject poverty and slavery was growing at a faster rate than in the days of the Conquistadores. On Independence Day in 1910, President Diaz kept the Indians off the street so as not to mar the joyous festivities.

In the midst of this misery a small but significant intellectual community emerged. Three of its members – Antonios Curo, Alfonso Reyes, and Jose Vasconcelos – established an institute called The Athenaeum. These men were cultured and highly educated. On the one-hundredth birthday of Mexico’s independence, they issued a manifesto. “The community that terrorizes over man forgets that men are ‘persons’, not biological units.”

Those words, along with the populist engravings of Jose Guadalupe Posada and the political zeal of the artist, Dr. Atl, influenced an entire generation of painters who were to change the face of Mexican art forever. Three artists would be at the forefront of this change – David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and Jose Clemente Orozco. However, in 1910 the political revolution had just begun, and the country wasn’t as yet ready for a cultural revolution.

That year, Diego Rivera was spending his third year in Europe on an art scholarship from the government. He had entered the San Carlos Academy at 10 years old, and now at the ripe age of 23 years, he was in Paris soaking up the work of Derain, Klee, Bracque, Cezanne, and Picasso. He made a trip to Italy and got his first insight into fresco painting, as experience which was to serve him well as a muralist several years later. He returned to Mexico in 1921.

In 1910, David Alfaro Siqueiros, the youngest of the three, was only 12 years old. The next year he also entered the San Carlos Academy. Three years later, he left his art studies to fight in the revolution. In 1919, he, too, was sent to Europe on a scholarship to study art. In Paris, he met Diego Rivera, who urged the young painter to get in touch with his country’s rich cultural past. Siqueiros returned to Mexico in 1922.

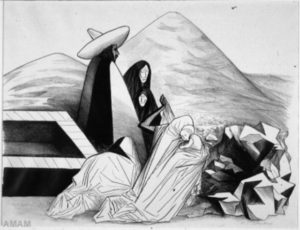

Jose Clemente Orozco had also studied at the San Carlos Academy. While there, he drew unflattering portraits of the teaching staff and was told he couldn’t draw. He wasn’t sent abroad to study. In 1910, he found work as a political cartoonist and draftsman. When Dr. Atl left the Academy to head a battalion, Orozco went with him. Because of a missing left hand, he wasn’t asked to fight in the front lines. Instead, he drew for the “Vanguardia,” a regimental sheet printed by Dr. Atl. The experience marked him for life. He was the only one of the big three who didn’t glorify the revolution.

In 1920, General Obregon, the incoming president, asked Jose Vasconcelos how to unite a mostly illiterate country. Vasconcelos suggested mural art to reach the masses – a technique used by their Mayan and Aztec ancestors before the conquest. As Secretary of Education, he commissioned Mexico’s best artists to paint murals throughout the country. But it was the big three – Siqueiros, Rivera, and Orozco – who will be forever associated with this discipline.

Though different in style and temperament, all three believed, as did many other artists of their time, that art is for the education and betterment of the people, not an abstract concept or vehicle for exploring whims. This perception of art was the raison d’etre for the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, an organization to which they all belonged.

To a great extent, the work of the Muralists was a collective product – a group expression created through years of close relationship. If one got an idea they could all use, no one was especially concerned. When Rivera introduced the technique of fresco painting, it was adopted by all. When another painter formulated the dense, fresh texture that was so different from the Italian murals, that, too, was incorporated.

There is a story that Siqueiros left a mural to tend to other business. A colleague put a head on one of his figures while he was gone. Siqueiros exclaimed that it was wonderful, and that he either did it in his sleep or it was a miracle. He joked that he’d leave again to see what happened. Orozco overheard the conversation, and made sure that it was repeated. Siqueiros was more pleased than ever.

In spite of the close collaboration, the work of each man was very distinctive. The government set no limitations, so each painter was free to work in his own style with his own techniques and views. Without looking at the signature (which wasn’t always there), it is easy to know which muralist painted what.

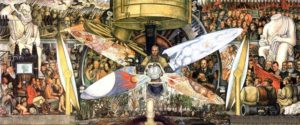

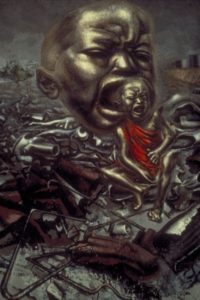

Siqueiros was the most innovative of the three. Although he started working in traditional fresco technique (watercolor washed onto damp plaster), he soon abandoned it to experiment with pyroxlene, a commercial enamel, and Duco, a transparent automobile paint. His work is recognized by his rapid, bold line and exaggerated perspective. His ability to integrate traditional Mexican art with innovative techniques was masterful. The result is original, powerful, and dramatic.

He was driven by the desire to initiate a new type of mural painting that relied on modern technology. Paint was sprayed, poured, dripped, and splattered giving way to an endless variety of accidental effects. He was among the first to experiment with acrylics, resins, and asbestos, and was quick to understand the possibilities of airbrush to apply paint.

His war experiences during the revolution convinced him of the need for politically committed art, and he based his subject matter on socialist ideals and modernist forms. Because of his love for all that was modern, he began to incorporate machinery, speed, science, and technology into his art. He was able to do this and still convey a message of social issues to the common people. He aspired to make art that appealed to the ordinary person, and he was very successful.

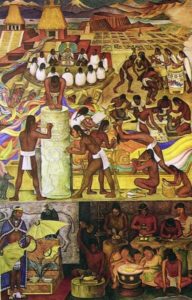

Rivera worked in a more traditional mode, and his work has the rhythm of architectural composition. He took everything he learned from European modernism, melded it with the art of ancient Mexico, and came up with a new form that would allow him to express his social and political ideas on a broad scale.

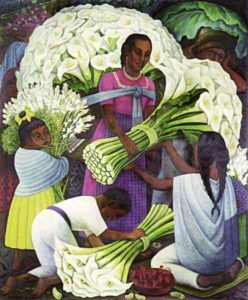

He was initially taken by the bright colors and light of Mexico, and he captured them in the vibrancy of his market scenes. Later, his bright colors gave way to earthy browns, oranges and shades of green and red, giving the murals the look of age reminiscent of the early indigenous murals. The new colors gave a sense of permanence and truth to his work.

Rivera’s subjects reflected his appreciation for Mexico’s history and its indigenous cultures. He gave the people a vision – a way of seeing themselves as great and noble. His role in Mexico’s rediscovery of its past and the roots of its culture cannot be overestimated. He made the Mexican people the heroes of his work. Many people today see Mexico through his eyes, and his art has affected the way we think about this country.

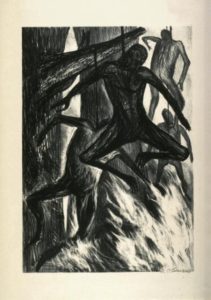

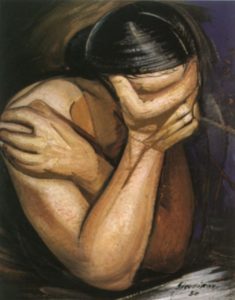

In contrast to Rivera’s murals glorifying Mexico’s heritage, and Siqueiros’s belief in a science fiction future, the work of Orozco was somber and full of dire prophecy. He was not impressed with man’s past performance and had fear of a growing dependency on technology in the future.

However, like the other two, he believed in the power of the mural as the highest form of art whose role it was to reach the people – to communicate and educate. Once he committed himself to mural painting, he never went back to the easel.

His emphasis was on human suffering, and in some pieces, the cruelty of the Mexican revolution. Unlike Rivera and Siqueiros, Orozco saw the revolution with the eye of an artist rather than that of an ideologue. He showed the horrors of war – executions by firing squads, pillaging, rape. Also, unlike Rivera and Siqueiros, the real subject for him was not the history of Mexico, but what lay underneath.

For his honesty, he was accused of showing Mexico in a disgusting and savage light. Many of his murals were defaced and the government wanted to whitewash his work. Art critics called him “sick.”

In the late 1920s, he painted a fresco mural at Pomona College in Claremont, California. Today it’s considered on a par with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel in Rome. In my opinion, Orozco was the best of the three great muralists, and one of the best painters of all time.

There is no question that “Los Tres Grandes” had a strong influence on how we perceive art in the twentieth century. Not only did they create amazing murals, they influenced the techniques and styles of subsequent artists and forced many to re-examine the role of art in society. The power of their work has yet to be fully evaluated and appreciated.

The Big Three – Books

- Mexican Muralists: Orozco,Rivera, Siqueiros by Desmond Rochfort 1994

- Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States by Shifra M. Goldman 1994

- The Mexican Muralists in the United States by Laurance P. Hurlburt 1989

- Contemporary Mexican Painting in a Time of Change by Shifra M. Goldman 1981

- Mural Paintings of the Mexican Revolution by Carlos Pellicer 1985

- The Mexican Muralists in the United States by Laurance P. Hurlburt 1981

- The Mexican Mural Renaissance, 1920 – 1925 Yale University Press 1963

- I Paint What I See by E.B. White

- The Mexican Muralists by Alma M. Reed 1960

It’s no good taste in a man like me,

Said John D’s grandson, Nelson.

To question an artist’s integrity

Or mention a practical thing like a fee,

But I know what I like to a large degree,

Tho art I hate to hamper,

For twenty-one thousand conservative bucks

You painted a radical. I say, shucks,

I never could rent the offices–

The capitalist offices.

For this, as you know, is a public hall

And people want doves, or a tree in fall,

And tho your art I dislike to hamper,

I owe a little to God and Gramper,

And after all,

It’s my wall…..

We’ll see if it is, said Rivera.

Arts in Mexico Series Index

Published or Updated on: May 5, 2007 by Rita Pomade © 2008