When European ships were wrecked at sea, a Christian burial was usually afforded those whose bodies washed up on the shoreline. That was not the case here. Somewhere on a desolate stretch of a Baja California beach lie the bones and cargo of a once majestic Spanish galleon. It was around 1576 when she vanished with all hands aboard. Such disappearances happened sporadically during the long, hard ocean crossings and were considered routine risks of the early Pacific voyages. The Spanish kept meticulous records of all those galleons that left Asia with their valuable cargoes and arrived safely at their port of destination in Mexico–and of all of those that didn’t.

For more than two hundred and fifty years, the crews that braved the waters of the expansive Pacific fulfilled the dream of Columbus by sailing west to reach China and Japan. As part of a steady and lucrative trans-oceanic commercial trade, they brought tons of silver coins and ingots from the port of Acapulco to Manila in the Philippines, a thriving commercial hub in Asia that formed an important trade link to China. For the so-called “Manila galleons,” as they were known, it was an exceptionally long, arduous voyage from Mexico to Manila; and it was an even more grueling return trip, laden with rich treasures from Asia, but fraught with life-threatening dangers.

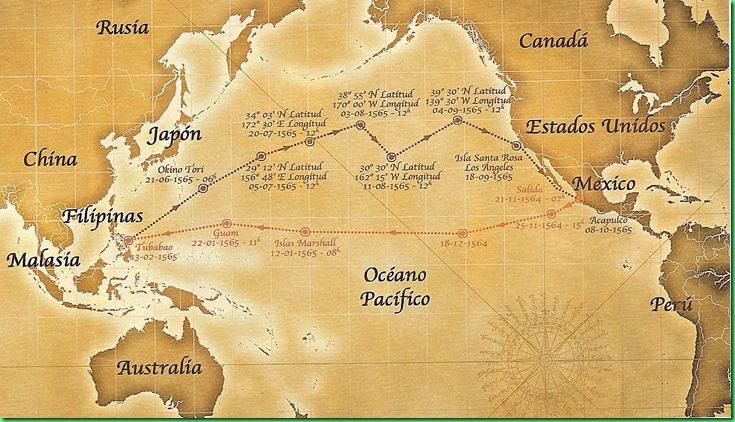

During the sixteenth century, the Pacific’s warm trade winds were not fully understood. On the southern route from East to West, it was a relatively fast two months voyage. On the other hand, the return trip from Manila was a different story; that is, until they found the ocean currents that would take them more rapidly eastward. It was an Augustinian friar, the explorer Andrés de Urdaneta, who theorized that the Pacific trade winds and ocean currents might circulate in a similar clockwise pattern to those in the Atlantic. (See The Pacific route to the Orient for more history of the trans-Pacific routes.)

On an expedition in 1565, Urdaneta proved his point. From that moment onward, Spain’s galleons on their return passage had to sail north from the Philippines to pick up Japan’s Kuroshio current, then steer northeast through rough seas in the direction of the Aleutian Islands.

There, they picked up the currents and winds that would drive them toward North America, before heading thousands of miles south down the coast of what today is California and Baja California, eventually arriving back at their destination in Acapulco. The ten-thousand-mile voyage was the longest trade route in the world at the time.

Among the eagerly awaited trade goods from the Orient were silk, spices, beeswax and Chinese porcelain. If they reached Acapulco safely, these goods were loaded onto pack mules and transported overland, either to Vera Cruz. for trans-shipment to Spain. or to churches and to wealthy Spanish families in Mexico City. Other parts of the cargo were trans-shipped by sea to Guatemala, Panama, Ecuador, and Peru.

In addition to the dangers of piracy and typhoons, the hard-working ship crews faced the real perils of starvation and dehydration. A best case scenario for the eastward crossing was about four months, but if the weather was against them it could take six months. Sailors often arrived in Acapulco emaciated, without enough strength to stand.

What they feared most of all, however, was death from scurvy, a debilitating disease not fully understood that resulted from a lack of fresh fruits and vegetables in the diet. Simply put, it was the dread of seafaring men the world over. Of all the grand Manila galleons that plied the trade winds from Mexico to the Philippines and back between 1565 and 1600, a few were never accounted for, having sailed into oblivion without a trace.

Fast forward about four hundred years to when a small group of American adventurers was walking on remote desert terrain along a seldom-visited part of Baja California’s coastline. In a place where there should only have been seashells and driftwood, they came across broken bits of porcelain and stoneware that couldn’t have floated to the coast and weren’t supposed to be there.

It didn’t take them long to realize that they had stumbled upon a shipwreck, but they knew nothing about her age or origins. It was exciting enough for them to begin making occasional visits to that godforsaken corner of the peninsula, far from any signs of civilization. For years this hearty little band of adventuring treasure-seekers camped on the strand at nights, and early next morning combed over the sands searching for anything they could find that would pique their interests. Although they had sworn each other to secrecy about the location, word got out. But that’s another story altogether.

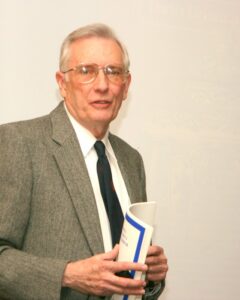

Enter Edward Von der Porten, a respected nautical archeologist and naval historian. He got word of the ship and, during two highly secretive meetings, was able to persuade the beachcombers that their efforts would be more rewarding if they joined experienced archaeologists to work on the site. The beachcombers had already been seeking ways of returning the porcelain and stoneware sherds to Mexican authorities and welcomed a means of adding them to Mexico’s cultural heritage. With his accumulated experience heading archaeological projects, and with the aid of colleagues familiar with the Mexican heritage program, Von der Porten was able to act as a liaison with Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) to turn the shoreline into a protected site that would enable him to direct scientific archeological evaluations and excavations.

During the first year at the wreck’s location, the team he assembled began piecing together the vessel’s identity. The ship was laden with Chinese porcelains, stoneware jars, and tons of Philippine beeswax in large blocks, a valuable commodity from which church candles and other goods were made. It quickly became apparent that this was indeed one of Spain’s Manila galleons.

Subsequent expeditions to the site turned up pieces of lead sheathing from the hull’s exterior, a Chinese Buddhist bronze lion, a Chinese bronze mirror, an astonishing variety of sixteenth century glazed porcelains, a set of compass gimbals, and a piece of Iberian pottery. By way of porcelain analysis, the archaeologists were able to narrow down the date of the wreck to about 1574 through 1579.

Archival research indicated that there were only a few “missing-without-trace” Manila galleons in the late sixteenth century. It was safe to say that this vessel was a sizeable, three-masted ship about one hundred feet long, which set sail from the Philippines one day in the late 1570s and was never seen or heard from again.

But there was something intriguing about this particular wreck on Mexico’s coastline, because she didn’t fit the typical shipwreck pattern that went down at sea. Why was it on land? Over time, Von der Porten’s small group of dedicated diggers and sifters began coaxing her to give up her centuries-old secrets. They realized that her contents were not in a single small area, but scattered along miles of the beach. The artifacts were clearly broken in one cataclysmic event, but what was that event? And how did the ship come so far, only to rest onto this lonely beach?

After several summers of sifting through the fine white Baja sand pondering this enigma, Von der Porten began to gradually unravel the mystery. While sitting at the shore under the unrelenting summer sun, next to one of the large thirty-pound blocks of Philippine beeswax, he noted worm holes up to three centimeters in diameter in the block. The worms had bored deep into the block. This particular type of worm—Teredo navalis, the dreaded shipworm—lived in salt water and bored into wood or any other soft substance that would shelter it. These worms could not survive on a parched desert landscape. And the worms could not have attacked the hull from the outside while she was afloat, because the hull’s exterior lead sheathing would have kept them out.

These worms must have attacked from within, which wasn’t possible at sea where the hull was pumped dry every four hours. The borings must have happened after the shipwreck when the crew stopped pumping and seawater seeped into the hull, with Teredo larvae swimming along in it. The beeswax was bored into from inside while she was flooded but still intact. A marine biologist determined that the worms would have needed to be submerged in the hull’s water for at least one year for them to have bored that far through the blocks of wax.

Von der Porten realized that the only way this could have happened was if the ship grounded gently onto the shore. Such a grounding could only have happened if the crew were dead, dying or unable to control her, allowing the prevailing wind to push her from her southerly course onto the gently shelving beach. If any of the crewmen were still alive that day when the ship grounded on the shore, they never lived to tell about it.

The remote, barren beach was unforgiving, and the desolate Baja desert gave no quarter. Any surviving souls would have perished slowly from scurvy, starvation or dehydration–their loved ones would never have learned their fate or known their last, lingering thoughts as they lay dying on a barren, uninhabited beach. Did their hands clutch the sun-baked sands as they struggled to stay alive? Or did they even lack the strength to leave the ship, and die in the confines of the mighty wooden galleon?

However long the ship lay offshore with her dead aboard, she was never spotted by other galleons sailing southward along Mexico’s extensive coast. As she lay crippled on her side for years on an uninhabited, inhospitable stretch of the Baja Peninsula, her only sounds were the cries from her creaking weather-worn timbers. With her masts still at full sail, the shore waves occasionally rocked her in the sands and took her sliding southward along the beach at full sail.

Then a storm hit the Teredo-riddled hull, smashed into her side, and drove the wreckage over the low beach front until it hit a dune line. Damaged hull fragments gave way and spread out for half a mile or more. The storm then backed around and drove the light porcelains and stoneware down the strand for miles. When the storm subsided, the receding waters left the wreckage strewn along the beach, where the Pacific winds soon covered it in the dunes. Over time, her wooden skeleton simply vanished into the fine white sand.

After pondering this scenario in his mind over and over again, Von der Porten surmised that there couldn’t be any other logical explanation to the mystery. This wreck indeed had been a ghost ship.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in ports around the world, stories abounded of “ghost ships” found floating at sea without a single man alive. Somewhere on a beach in Baja California, a real ghost ship has been discovered more than four hundred years later. Her name when she sailed on her final voyage is believed to be the San Juanillo, one of Spain’s great galleons that disappeared without a trace. Work continues at the wreck site that is part of Mexico’s cultural heritage and which will help us understand more about this important chapter of world trade during the Spanish-colonial era.

In a few years, a permanent museum exhibit in Ensenada will display the artifacts and make the story available for all to enjoy. For the determined archeologists who continue sifting in the heat through the fine, white sand, it is truly the stuff that dreams are made of.

This story of a lost Spanish galleon is dedicated to Edward Von der Porten, a man I was fortunate to meet during a gathering of scholars at the California Mission Studies Association (CMSA). As he narrated the circumstances of the discovery, I realized that it represented the opportunity of a lifetime to give voice to a long lost ship and its crew after more than four centuries of silence. Ed, who was an educator, nautical archaeologist and naval historian, passed away in 2018. His work with INAH was invaluable to preserve the memory of the souls who manned that lost ghostly galleon.

Interesting story. I have a slightly different point of view, just as a counter to the privileging of “majestic” galleons, which basically were engaged in the theft of resources from Mesoamerica. During this same time period, mostly in the sixteenth century, the population of the greater Valley of Mexico decreased by 90% thanks to the Spanish occupiers, while the mendicant orders did nothing. Some scholars are tempted to call that genocide and ethnocide. The article is fascinating, but I object to articles that deny this historical fact. It should at least have a disclaimer, otherwise, we are misrepresenting history.

Hello Mr. Robert, thank you for your comments, which I respect. I’m pleased that you found the article about the discovery of a lost Spanish galleon, and Mr. Von der Porten’s role in its archeology, to be of interest. I penned this story for MexConnect’s general reading audience to inform them of a little-known event in Mexico’s 17th century nautical history within the Spanish Empire. It certainly was not meant to, as you state, deny historical fact. Having said that, I think it appropriate to explain to the general audience that your mention of “the mendicant orders” refers primarily to the Catholic Church’s Franciscan, Dominican, Augustine and Carmelite monastic religious orders, who were active in Spain’s colonization of the so-called “New World.” My question to you: if you were to write a disclaimer for an article about this nautical event, what would that disclaimer look like? Thank you in advance. Kind regards, Joseph Serbaroli

Joseph Serbaroli, no offence but you story about the Baja Manila Galleon is way off base. First of all, you rely upon statements made by Von der Porton who was not an archaeologist let alone a University graduate certified marine archaeologist. He had no experience diving and salvaging a historic shipwreck. He and his group went to the secret location on the beach were there for one reason and that was to find treasure and that’s why they didn’t share their location with the public. They had the greed Factor. I spoke to him 20 years ago on the phone and he was not friendly and treated me like I was some sort of a spy which is not the case. I am a published author of a book detailing shipwrecks and my adventures researching them, searching for them and salvaging them.

The mere idea of the ship being broken in so many pieces in scatter along many miles of coastline is ridiculous. There’s a thing called a scatter trail. I won’t explain more about that. I know who some of the people are who were on that beach who are politicians from San Diego who took one of the unbroken bowls of ming dynasty and when I have written them several times and even tried to call them, they refuse to respond. The bowl would be worth perhaps $500,000 based on an auction that took place of a similar bowl that sold for 35 million dollars! I know where the wreck is and it’s canons and anchors. People I know in that area also know the location on the beach and offshore. You should have really interviewed me for your story but I’m not sure I would have given you the facts. Your story is also misleading when you show photographs of Spanish silver cobbs (pieces of eight) when infact the ship carried primarily hundreds of thousands of Chinese porcelain, objects of gold in many boxes, Jade and ivory figurines, custom jewellery studded with gems & boxes of diamonds and rubies. Plus personal belongings of the many hundreds of passengers. It was only galleons leaving Acapulco Mexico and heading back to Manila that carried up to 5 million gold and silver coins and hundreds of bars of gold and silver from the mines of Peru and Mexico. My company and I are the ones who found the beeswax wreck at Nehalem Oregon offshore in 1988 and we had a salvage licence issued by the state. I have the exact location of 5 Manila galleons in the Philippines; one of which was found in 1987 and partially salvaged by my late friend Sir Robert Marx. He sold to Ming dynasty tea cups circa early 1600s for $250,000 each in Florida. If you want more facts I might be willing to speak to you. I am also a rather famous singer who sings mostly Frank Sinatra songs and who was indeed my personal friend beginning in 1985 in Palm Springs California. I’m also winner of X Factor music TV show show 4 years ago. I also own an island in the Caribbean and I’m dealing with the Discovery channel concerning a reality television series about our exciting shipwreck work and adventures.

San Diego

She is

?? [editor]

I’ll offer a few comments on William’s note, but to really understand the story, get a copy of “Ghost Galleon: The Discovery and Archaeology of the San Juanillo on the Shores of Baja California,” Texas A&M University Press.

My father, Edward Von der Porten, was recognized throughout the professional nautical archeology world. Right, he had no nautical archaeology degree — such didn’t exist when he went to college. His BA and MA were in history. He did work on several shipwrecks and worked with the early professional nautical archaeologists.

The “greed factor” is really laughable! The nearly 20 expeditions were funded by the participants. Often, they had to contribute to bring the official Mexican archaeologists to the site. Nobody got anything but experiences, photographs and memories. All the materials went to INAH in Mexico City. In fact, this work led to the return of materials which had been in the US (without authorization) to INAH.

I’d welcome “William” to provide links to the sale of any similar materials in the hundreds of thousands of dollars! Christie’s Auction House told the original beachcombers that their finds were worthless — and intact bowls (which they did not have) were worth $200.

“Many hundreds of passengers”? The total compliment — crew & passengers — probably numbered 70 to 100. This was no Carnival Cruise ship!

Read the book. Contact the folks at INAH. This is a story of history and archaeology, not treasure hunting.

Dear Michael – I am the author of the shipwreck publication “the ceramic load of the Witte Leeuw’ published in Amsterdam 1982. I had been in contact with Edward for many years and I received a pdf of the book from his grandson but I have lost the mail address because the provider stopped. could you send it to me please?I also wish to send a copy of my dissertation in which I refer to the images.

greetings, Christine Ketel (van der Pijl-Ketel)

I always found Edward Von der Porten to be a considerate and humble man. In my many encounters with Ed across several years, I witnessed zero instances of boast or bombast. He was always kind, gracious, and welcoming to my wife, daughters, and me. He lived in a modest house and drove an old Chrysler mini-van. Ed has enjoyed the international respect of numerous mariners, historians, authors, film-makers, museum curators, archaeologists, and marine archaeologists. His book Ghost Galleon has been met with much deserved favor. It is curious to find one who lived in such unassuming circumstances to be charged with “greed Factor”–especially by William who must tout his fame and exult his Caribbean island ownership. Perhaps William understands greed better than did Ed.

Very well said, I hope we continue this conversation . Thank you all for this very interesting article.

I also knew Edward who invited me to join him on one of the early Baja explorations of the ship. His description of what we would be doing was reminiscent of Shackleton’s ad for crew: hard work, butal conditions and no pay. Still, I regret that I did not take him up on his offer. It is true that he was secretive about the location. Understandable given that there are people who would try to loot such a find. But the assertion that this was because he was seeking treasure is defamatory. As his son has pointed out, the recovered items from the ship have been turned over to the INAH.

I lost track of Edward over the years and was sorry to hear that he died. But I am heartened to see, and I am sure Edward would be gratified, that his son continues the work of the Drake’s Navigator’s Guild. He was a passionate and serious historian who made numerous important contributions to our understanding of nautical history.

Hello,

Interesting article. I have a question: I read an article about this wreck in SF a while ago. Mr. Von Der Porten called the wreck the San Felipe. Now it’s the San Juanillo. Any idea why?

Here’s a link to the article.: https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/ship-s-story-revealed-in-435-year-old-wreckage-2334012.php

Thank you

Hello James, thanks for the question. There’s a good reason why Ed von der Porten originally surmised the name of the wreck that beached on Mexico’s Baja coastline. Having spent many years researching the wreck, and based on the types of porcelain shards and other excavated relics, he narrowed down the timeframe when the wreck could have happened. In that timeframe of several years there were, recorded in the Spanish archives, about 4 Manila galleons that vanished without a trace on the eastward voyage AFTER they left Manila. Originally Ed surmised that it was the San Felipe, but he was always quite candid & honest in stating that it was not 100% certain, as it could have been one of the other 3 galleons that vanished without trace. A few years later, evidence was found that confirmed the San Felipe disappeared elsewhere (I believe it was closer to the Philippines). Before Ed finished writing his book about the wreck, he discovered that the wreck was actually the San Juanillo, and he shared that information with me. He passed away on April 9, 2018 and his son Michael was able to get the manuscript published in 2019. It is available today on Amazon under the title: Ghost Galleon: The Discovery and Archaeology of the San Juanillo on the Shores of Baja California (Ed Rachal Foundation Nautical Archaeology Series). As with all of Ed’s books, it is a scholarly & fascinating piece of work, and a story that is well worth the read.