Mexican History

Stories about the creation of the universe are found in many places in the world throughout history. We have our own creation stories: Creationism, Intelligent Design, and Darwinian Evolution. Whichever one and for whatever reason you choose, all are attempts to explain who we are, why we are here, and is there any real purpose in all of this. We do not have the time or the space in this article to go into the controversy over science and religion or the [alleged] contradiction between the two for — whatever the “evidence” or “truth” of the matter may be — these “creation stories” are simply mental constructions we carry around in our heads, none of which would even exist were it not for human minds to contemplate them. It is with this in mind that we should approach a Huichol story of the creation of the sun, which I obtained from a Huichol friend of mine.

A function of mythology (a term I use advisedly) is to explain and account for natural phenomena, such as mountains, valleys, natural formations, and human beings. Aetiological myths attempt to explain the “causes” of things — they are a poetical outward means of expression that provides ready-made answers to difficult questions about human existence, thus allowing people the relative freedom to get on with their daily business.

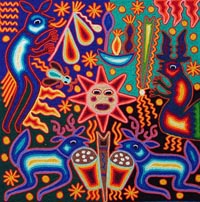

Creation myths exhibit both universal elements and particular features. Culture heroes or saviours of the human race are common, for example Quetzalcoatl as the Toltec culture hero of the classical Aztecs or Manas of the Turkic heroic epic cycle known by his name, Manas. Examples of particular cultural features are the Quiche Maya concept of “white” signifying “book” (ie. the Popol Vuh) or the peyote pilgrimage of the Huichol Indians. Problems of interpretation of these myths and the practices behind them involve both surface meaning and hidden or deep structure. A superficial comparison, say, of the Huichol Trinity, the Deer, the Peyote, and the Maize, with the Christian Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, may appear to show that the Huichols borrowed the idea from Christian missionaries, which is not the case. Therefore, we must look beneath the surface in order to uncover the inner or hidden linguistic or cultural meaning of the myth in its own context.

A Huichol friend of mine, Juan Bautista Carillo, came up with the idea of a trilingual edition (Huichol, Spanish, English) of traditional Huichol narratives from his home base of San Andres Cohamiata in the Huichol sierra. For various reasons, the project never came to fruition. However, I did manage to salvage one such account of the creation of the sun as narrated by Eusebio Lopez Carillo, recorded by Joaquin Bautista Carillo (my friend), and translated into Spanish by Julio Carillo, all of San Andres Cohamiata. The original version entitled Historia El Tau-Sol (Huichol and Spanish for “sun”, which I translated using both the Huichol and the Spanish versions, came to about 3368 words, obviously too long for this article. Therefore I shall give a condensed version of the main outline followed by an attempt to explain its meaning and significance.

This is not an account of the creation of human beings but of their main means of sustenance, namely fire and the sun. Accordingly this particular Huichol narrative begins with the creation of the first hearth fire.

When the people discovered that fire alone was not enough to light up the world, they began to sacrifice children to bring the light. It did not work. Then the owl messenger, who represented the hearth fire, told Paritsika, a famous hunter, that burning children would never bring light to the world.

Paritsika then announced to the people that a magical boy had been chosen for the task. The magical boy, who had a premonition that he was the Chosen One, assured his mother that he would not suffer the same fate as the other children who had been sacrificed. The boy set out on his mission. He played a hoop and arrow game in which he would strike his hoop with an arrow causing it to roll along the ground, thus raising much smoke and dust, the origin of human diseases and epidemics. To counteract this evil, Great Grandfather White Tail Deer, instructed the people to place five prayer arrows in each hole where the earth had caved in. This enabled the people to control diseases to some extent.

The people searched for a name for the boy, such as “He of the Feathered Sombrero,” of “He of the Crown of Arrows,” but none seemed quite right.

In desperation, the people went up into a high mountain, where a quail and a turkey appeared — in those days animals were really people. The turkey person raised his head and said “aru, aru, aru,” but nothing happened. The second time he said “tau-tau-tau” and more light appeared.

The sun then came out and was called Tawexikia and Tayeu (Father Sun, our Elder Brother). But the sun was too close to the earth and so the snake people grew wings so that they might fly up into the sky and eat up the sun.

In defense, the sun established red, blue and grey stars in the sky and the snake people failed.

Finally, messengers were sent to ask Great Grandfather Nakawe to raise the sun up higher so that it would not harm the people. They gave Nakawe a bottle of wine and he got drunk. Although in a drunken stupor, he still managed to lead them on a pilgrimage during which he had several mishaps but continued singing all the way — the very songs the Huichols sing to this day.

Finally, Nakawe pointed his mumuxi (staff) in all the cardinal directions and the centre exhorting them to assist in raising up and supporting the sun. Five times he raised up the sun and then asked the people where they wanted it. At the fifth raising, he left the sun where it is today.

“Stay at this height forever,” Nakawe told the sun. He fastened the sun in place with pine tree trunks. That is why the Huichols, in commemoration of the tree of our Father Sun, still use pine trees to support the roof of the calihuey, the god house in the ceremonial centres.

At last the magical boy received his name: Wexikia, “The Sphere of Great Rays,” the sun as it is called today. From that time on the people began to live happily in the light of the sun.

This aetiological or “mythical” account of the creation of the sun explains and justifies many Huichol beliefs and practices to the present day. It explains how the sun happens to be where it is today. Various natural objects in the Huichol sierra are explained by the appearance of the magical boy with his hoop and arrow game. Today, a human Paritsika safeguards the ceremonial centre. The calihuey is supported by pine trees just as Nakawe used them to prop up the sun. Reminiscent of the Five Suns of the Aztec calendar, the number five runs throughout the Huichol narrative. The uncontrollable actions of the magical boy with his hoop and arrow game account for the diseases that plague the human race. The jícaras or ceremonial gourd bowls used to catch the blood of the sacrificed deer or bull in the peyote fiesta celebrate the coming out of the sun. It all makes perfectly good sense, if you are in the right state of mind. Some years ago, when I was in the calihuey in Las Guayabas, I noticed a bunch of zacate or weeds hanging from the roof. When I asked my friend Nacho, the presiding marakame or shaman-priest, what it represented, he told me it had been there since the beginning of time. Under the circumstances I believed him.

There are many different forms of mythology. As the old myths lose their force as explanations of natural phenomena, we tend to reinterpret them in our own words and in different contexts. If the past is any guide — and if we survive our own stupidity and intolerance — future generations may well look upon our “modern” science as old-fashioned mythology. Some cosmologists tell us that the universe will end in so many billions of years, others that the universe is expanding at an ever-increasing rate. Shamans, like my friend Nacho (now deceased), believe that they can leave the body at will, travel to the spiritual realms, and bring back messages to the people. Ill-informed people discount and even ridicule such “paranormal” claims.

Nevertheless, the Huichol story of the creation of the sun explains a natural phenomenon to the satisfaction of the Huichols. In fact the Huichol “myth” serves the same purpose as the most advanced “scientific” explanations of the universe, which are often quite bizarre, even unintelligible, to the average person.

But whether the explanation be “mythical” or “scientific” it serves the same purpose: to satisfy the human thirst for knowledge.