Mexican History

I met several people at the Fiesta de las Plantas Medicinales held at Atotonilco El Alto in 1990, among them Jesus Higuera (Katuza), who had held the impromptu peyote ceremony when the Huichols refused to participate for fear of the federales.

It was there I also met Armando Casillas Romo, who was promoting a book he had written on traditional Huichol Medicine (Medicina Tradicional Huichola, Guadalajara, 1990). From Armando I learned about the Huichol concept of disease and its treatment.

Contrary to my earlier impressions, some Huichols were also curanderos who used herbal remedies in treating a variety of illnesses. I also learned more about the “Unknown Mexico” that the Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz had written about more than a century ago, including some of the hidden intrigues and undercurrents in Huichol society.

At that time Armando was working with the Ministry of Health and had spent about three years on and off among the Huichol recording their medicinal practices. He reported that while few women speak Spanish, many of the men do but that they did not welcome strangers in the Huichol sierra. The best way to approach the Huichols was with gifts of old clothes, vitamins, medicines — anything they might be able to use. In that way, one showed good will and was not simply a tourist with a camera. Even so the Huichol would accept a stranger for a week or so but if one stayed longer they would want to know why.

This is especially true of traditional native societies. For example, Huichols, in particular traditional shamans, seldom venture out of their central communities and ranchos in the sierras, and when they do they are somewhat suspect by the people back home, especially if they stay away too long.

Armando informed me that the shaman who failed to show up for the workshop on Traditional Huichol Medicine at Atotonilco was not in favour with some of the more traditional Huichol shamans, and that they would consider Katuza’s impromptu peyote ceremony for members of the workshop quite disrespectful. It was then I really began to learn the do’s and don’ts of living in Mexico.

Armando also confirmed my conclusion that most of the religious, social service, and government groups working in the Huichol sierrra were generally regarded with some suspicion by the Huichol as having vested interests. It was strongly felt that government officials took a paternalistic attitude in telling the people what they, the officials, were going to do rather than asking the people what they wanted.

I can confirm this from my own experience. Many years ago in Canada I applied for a job as an Indian agent in the Yukon Territories. The interviewer asked me how I would handle a problem that came up with an Indian band. I replied that I would ask the people what they wanted or needed. The interviewer promptly closed his notebook and said: “We had someone like you once in the Indian affairs Department and we are still trying to get the stench out of our nostrils.” His exact words. Needless to say I did not get the job.

Katuza and I became fast friends after our first meeting at Atotonilco and we still spend many hours discussing native religion and folklore at his temazcal (traditional sweat bath) in Ajijic. It was there that I first met Ignacio Montoya (Nacho), a Huichol shaman from Las Guayabas deep in the Huichol sierra.

Huichol shaman, Buddhist monk and a temascalero

On May 8, 1991, I had gone to visit Katuza and found several people also visiting, among them the owner of the “Esoteric” book store in Guadalajara and an English Buddhist monk, Losang, who had been assisting Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, a Tibetan Buddhist meditation master. I had been attending their weekly meditation sessions and was quite familiar with Losang and his particular philosophy of Lamrim Buddhism. The lectures were held in an improvised Buddhist temple right behind the Catholic church in San Antonio Tlayacapan, Lake Chapala, a rather inauspicious place for a Buddhist temple as it turned out later.

We had a meal of herbs gathered in the mountains around Ajijic cooked in hot chili. Not bad. Afterwards the conversation turned to religion and spiritualism.

Losang had studied Tibetan and Sanskrit sutras in India. The sessions in Ajijic were patterned after the Buddhist monastery system in which the master delivers his speech and the disciple directs the ensuing debate, strictly on line with the topic.

As we were talking, Nacho, a Huichol mara’kame from Las Guayabas, dropped in unexpectedly, obviously for a meal. He spoke Spanish but conveyed more by his sardonic laughter, almost as if he were laughing at us vecinos (neighbours) trying to influence the Huichols or get in good with them.

It was a strange scenario — a Buddhist monk, a Huichol shaman, and a temascalero (professional builder and operator of the temazcal). As for me, I sat on the side lines taking mental notes.

The discussion about Buddhism, yoga, and the peyote religion was enlivened by the story of the foreigner from Spain who came to Ajijic wanting to become a mara’kame. He actually went on one of the peyote hunts to Wirakuta but was made the butt of Huichol jokes for his over-enthusiasm. A failed actor and a sometime painter, he went through all the histrionics of becoming a mara’kame. He began to believe he had been transformed into a genuine sorcerer. He never quite made it as a shaman but, it was said, his experience with peyote made him a better painter. At that time a sample of his work hung in the Chapala cathedral. Unfortunately he forgot to renew his immigration papers — for eight years — and was deported back to Spain. He left Mexico wearing the full ceremonial dress of a Huichol shaman and went home to his wife and child in Spain. He never returned.

Katuza showed Losang posters for the planned 1992 Native Congress in Mexico City celebrating not the alleged “discovery” of America by Columbus in 1492 but rather the 500th year of Indian survival in the face of the European and British genocide against all the native peoples of the Americas. Losang was polite and appreciative of the hospitality but I sensed that, while they all seemed to agree that there were similarities between native American religion and Buddhist philosophy, the Buddhist priest tended to regard the former as rather more superstition than religion, a rather biased opinion, I thought, considering the lectures I had just heard from the meditation master on the “Hungry Spirit Realms” of Tibetan Lamrim Buddhism. Nacho looked on impassively during the conversation. He replied only when spoken to and then only in short, clipped Spanish phrases. When asked about tourists in Huichol country, Nacho replied that many visitors came to San Andres during Semana Santa (Holy Week, Easter) and the Huichols put on a performance for them which they regarded as a joke on the tourists. The real ceremonies are not staged for the benefit of tourists with cameras.

After the meeting at Katuza’s house, Nacho and I became friends. I went to visit him shortly afterwards.

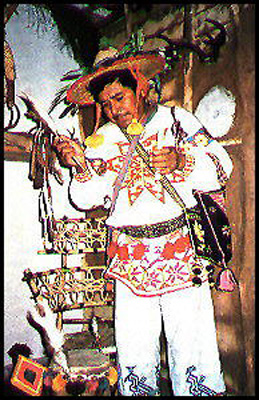

The house in which he was living in at the time had a peculiar rectangular shaped front, boards over the windows, and a battered wooden door, an abandoned wreck. Two young Huichols let me in and motioned toward a long narrow rock-strewn lot surrounded by a high wall. At the far end under a shade tree, resplendent in his brilliantly embroidered outfit, feathered sombrero by his side, sat Nacho. There were two women close by, one nursing a baby, the other engaged in that never-ending task of Huichol women, embroidering. The distance between me and Nacho seemed to increase as I walked toward him.

After the earlier conversation about sorcery and witchcraft at Katuza’s house, I half expected to be zapped with some kind of magical thunderbolt for invading the inner sanctum of a Huichol shaman. And indeed, he did look like a monarch seated on a rocky throne in the midst of desolation.

Nothing happened. Nacho was friendly enough, although I had been warned that as a gringo I would be sized up to see what “gifts” he could coax out of me. I ignored the advice and suggested we might exchange language lessons — Huichol for English and English for Huichol. He seemed quite interested in the text books I had brought with me, although not before asking me for my watch, pillows and blankets, and a ride in my car to Guadalajara. We agreed, however, that, while material things were important, “gifts” of the mind and spirit were more important.

We parted as friends and he welcomed me back again (without the gifts).

That was my introduction into the magical world of the Huichol.

Over the years I tried to help the Huichols sell their art to tourists, with some limited success. I became involved in a project intended to eliminate the middleman and give the Huichols a fairer price on their arts and crafts. But there were too many obstacles, not least from unscrupulous entrepreneurs with vested financial interests. Besides, the Huichol live in a different time and space from the rest of us. Still, we can learn more from them than they can learn from us about living in harmony with nature, although of course encroaching “civilization” is gradually changing their lives as well.

As I mentioned, 1992 was the year of the celebration of the survival of native peoples after 500 years of conquest and oppression. I did my little bit by researching the historical background of certain Aztec rituals and traditions to be used in the celebrations. Sometimes native peoples lose so much of their beliefs and traditions in the face of the missionaries and government officials who try to change them that they need someone like me to remind them of their past.

Huichol healing ceremony

In this same year I was invited to a curing ceremony at Canacinta, not far from Ajijic. The ceremony was held at Nacho’s new lodgings, a gate house at the entrance to a small rancho, where he was “house-sitting.”

After the usual mishaps, flat tire, trouble with the tape recorder, and stops to buy food and drinks, we finally arrived to find two Huichols waiting for us. The older man was the senior mara’kame, the younger man his assistant. After the initial greetings, we sat around for what seemed hours, the supposed “schedule” for the ceremony apparently forgotten. I had to remind myself that we were on Indian time, although Nacho had a wrist watch to mark out time periods of the ceremony for the head shaman.

To prepare for the ceremony, Nacho laid out a kind of altar in front of the chief mara’kame. Then he carefully sharpened some prayer arrows, which he stuck in the ground by the altar. Beside them were offerings of his takuatzin (case for carrying sacred arrows), a decorated beaded bowl filled with peyote buttons, a homemade guitar and violin, a candle, some feathers, and matches for lighting the candles.

The mara’kame began the ceremony by first laying down his muwieries (special prayer arrows) and his fur-covered staff of office alongside the other offerings. Then he picked up the prayer arrows and held them close to the side of his face, as if his source of inspiration came from them. He began to chant in a low almost inaudible voice, as if he were communing with himself. To my surprise the others continued laughing and talking as if nothing were happening. Gradually his voice became louder and everyone seemed to pick up and take notice.

I did not understand the Huichol words, of course, but I detected a pattern in his singing. Many Huichols actually have very fine voices and are quite musical. At times the chanter’s voice rose to a high falsetto then sank down to a louder refrain punctuated by a strong stress or grunt, at which point the singer stopped and took a bite of peyote while the young assistant took over momentarily with the same sing-song chant accentuated with very soft high falsetto notes.

Nacho’s wife, Lupe, was the patient. She sat on a mat in front of the mara’kame, who wafted his muwieries over her entire body. Then she held up her hands, palms up, and the shaman spit lightly on them. He listened to her heart as he continued to brush the feathers over her. Then he sucked at both sides of her head, stood upright, stared over the wall toward Lake Chapala, and then spit into his hand. He mumbled a few words as he picked out a lump, which he inspected closely before carefully depositing it in the fire, thus destroying the source of the problem or disease.

Afterwards the assistant explained to us that in his mind’s eye, the shaman was going through the pages of the book of life of the patient to find the source of the problem. He also told us that shamans sing in different ways depending where they come from but they receive their main inspiration from dreams, if not all the words and content.

The idea of a book is not is not uncommon even for non-literate traditional singers or story tellers. The Tibetan bard Dickchen Shenpa used to stare at a blank piece of paper while reciting the vast Gesar of Ling epic cycle, a performance which lasted for weeks.

Our shaman, too, continued for hours without any hesitation or loss of words. When we left the shaman continued chanting. Katuza remained behind and reported that he continued chanting the whole night through in an invocation to the spirits of Lake Chapala.

The pre-Hispanic gods are still alive and well in certain parts of old Mexico.

Part 3 of a seven part series

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people I: a disappearing way of life?

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people II: fiesta of medicinal plants

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people III: the shaman

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people IV: ritual dance

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people V: journey to the sierra

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people VI: Peyote Fiesta

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people VII: return from the Huichol sierra