Arts of Mexico

An old man smiles, crooked teeth in a beautiful mouth, head cocked to the left, eyes squinting with delight. A young woman, softly rounded and warmed by sunlight, gazes hopefully into the future. A fisherman stares pensively into space. He waits, expectantly, but resigned.

The portraits are evocative, the technique flawless. I wander through the small gallery and am struck by the integrity of the work. Who is this artist whose brushwork seems to capture so effortlessly the people of this little mountain village?

A week later, I return, this time to talk to artist, Javier Zaragoza. I find the man to be as generous, warm, and intense as his artwork. I knew he had lived in the U.S. most of his adult life, but I’m curious about where he had learned his craft and why he returned to this tiny fishing village, the home of his birth, after so many years.

“I was six when I started to paint,” he recalls. “It all started at the public library here in Ajijic. There was this woman, Neill James. She was a great woman, very generous. She gave us kids everything – watercolors, paper, brushes, and even furniture to work on. I spent my weekends painting all day. As we got better, she brought better brushes and paper and invited us kids to keep working.”

Soon the library was covered with paintings, and James started to sell the children’s work. Christmas cards would go for a peso and a painting for as much as 50 pesos and the money went to the young artists. At that time, a worker had to put in eight hours of hard labor for 25 pesos.

When Javier was 13, James sent him on a five-year scholarship to the Instituto in San Miguel de Allende. “They had models and outdoor painting,” he says, “and I love that, but it was all in English, and I didn’t understand the teachers. It was frustrating.” Two years later, he returned home.

“How did your parents feel about the scholarship?” I ask.

“Well, they were very proud. My father was a fisherman and my mother, the wife of a fisherman. I remember that there was just enough to eat so whatever I could do or whatever people offered me made my father happy. He encouraged me to go to San Miguel de Allende.”

The experience in San Miguel didn’t dampen Zaragoza’s enthusiasm for art. When he returned to his village, he continued to paint.

“I was very inspired. I knew I was going to be a painter. I didn’t have much of an art education, but I had a pencil, brush, and paint, and the time to do anything I wanted. I could see my mistakes, but it didn’t discourage me. I was even commissioned to paint six murals for a church in Ixtlahuacan, a neighboring village. It was hard because I had no technical books, but I was so pleased. I felt like Michelangelo.”

At the age of 18, he decided to emigrate to the States. “I was ambitious,” he says. “I wanted to be a big painter, and I wanted to make money. Well, I had a big surprise. I didn’t speak English, and I could only get work as a laborer.”

Zaragoza went back to school. “I knew I needed English. Even when I tried to get work in a place related to painting, they’d ask me if I spoke English. And I knew I needed to study more art. I enrolled at the LA Technical College and then at the Pasadena Art Center. It took me seven or eight years to finish school.”

Those years of education paid off. He got a job with Gannet, one of the biggest billboard companies in the world, and felt like a success.

“I made good money, and I wanted money, so I was very happy. I still dreamed about painting fine art, but I talked to American painters who quit the company and went to work for themselves. They weren’t making the money I was making. I watched all this, and I didn’t have the courage to leave. I wanted to reach for a star, and then I thought the star is too far… too risky, and I was happy to have a paycheck.”

Zaragoza left Gannet after 24 years to do backdrops and movie sets for Warner Brothers, but the need for studio painters was on the wane. “It didn’t matter how good you were,” says Javier. “The computers could do all the tricks and short cuts.”

The artist found work in Oregon painting murals on steel billboards, but by then he was already thinking about returning to Ajijic. His children were grown and they encouraged him to follow his dream. In 1999, he returned with his wife, Gloria, who plays a very important part in his life. “This was a new beginning for me,” he says, “and it’s still like a dream. I have four children, and they were very happy about my coming to Mexico. They’re proud of what I’m doing and I’m proud, too. We all knew that it was time for me to jump to that star that I had dreamed about. And maybe I’m already on that star.

“I have so many privileges now. I can paint anything I want, not just faces, but expression and gesture. I have the time to paint what and how I feel, and there are so many things I want to try. I was very lucky. I benefited from the kindness and generosity of Neill James.”

I ask him if that’s why he has been so generous with his time for the children of the village.

“It was part of the dream I had when I thought about coming back,” he says. “Children need opportunity. We are about 35 artists in Ajijic who all benefited from Ms. James. She encouraged our talent by giving us that opportunity. I want to do the same for this generation of children.”

Today, he can say his students are his inspiration. “These kids in my classes, they call me maestro. Wow! Am I? That gets me inside and feels good.”

Javier Zaragoza lives his vision. His life, like his work, is full of passion and humanity. The faces that look out through his portraits reflect the immense love he has for his village and its people. And the people in turn love him. The good son has returned giving back to the community what was given to him.

As a gift to the village, he painted a 20 by 22 foot mural on the south side of City Hall in Ajijic, its title “Origens of Ajijic 1472.”

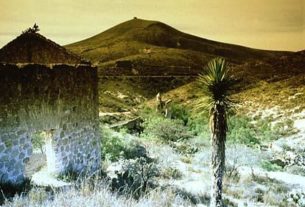

The mural pays homage to the people of his village, to his neighbors in the villages of El Chante and San Juan Cosala, to his ancestors, and to the lake, which was then and still is, central to the lives of the people in the area. The mural honors the sacred aspect of the lake where the indigenous people danced and gave offerings to give thanks to Michicihuath, goddess of the lake, for her abundance, and toTloloc, god of rain, for keeping the lake full. Local village people have served as models, the figures often being 8 feet high. The background is Ajijic’s mystic mountains over which reigns a huge image of the goddess.

“When you retire, you can do what you want,” he confides. You have fun when you commit to something and live up to your spiritual potential.”