The church bells have been tolling most of the night, interrupted only intermittently by the blast of rockets soaring into the night sky. One resounding boom echoes throughout the city at midnight. This is when thousands of pilgrims will join the Processión del Señor de la Columna (Procession of Our Lord of the Column — so named for an image of Jesus, his bruised and battered body bent over a column, his bloodied cheek scarred from Judas’s kiss of betrayal). The much venerated image sets out from the Sanctuary church of Atotonilco on a 12-kilometer walk to the church of San Juan de Dios in San Miguel de Allende. This procession marks the beginning of the celebrations leading up to Santa Semana — Holy Week — in Mexico.

We’ve set our alarm for 4:30 to give us time to wake up a little before we meet others in the Jardin, or main square at 6:00 a.m.

The streets are dark and empty, yellow lamplight falling on the cobblestones; the crickets sing as they do — endlessly — from behind stone walls. We cut through the deserted main square and walk down to Insurgentes, the street the local newspaper has told us will lead to Avenida Indepencia where the procession of believers will arrive at dawn.

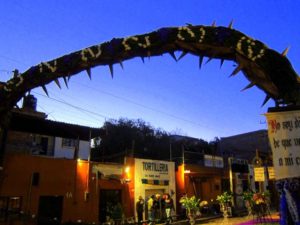

As we near Calle San Antonio Abad, we know we’ve arrived. It’s still dark, the cobblestone streets lit only by the lamplight along the adobe walls or lights from the odd tienda that is open, offering fruit juice, coffee or pozol, a drink made from corn. Garlands of flowers are strung across the streets and a huge crown of thorns bridges one of them. Men, women and children are scattering the procession pathway with fennel and chamomile, the fennel symbolizing the betrayal and abandonment of Jesus by his disciples and chamomile representing the humility of his mother, Mary. Other women are scattering confetti and flower petals over the fennel and chamomile.

Mornings are cold here in the mountains and most people are dressed in parkas, wrapped in rebozos and wearing woolen hats and scarves. Children are shrouded in fuzzy blankets, families sit against stone walls, draped on top of one another, asleep. Steam rises from cooking pots; small stands are set up where women are frying tortillas. Though there is an aura of celebration in the air, this world is mostly silent but for the occasional blast of fireworks that sens arcs of brilliant white light into the still-dark morning sky.

It’s early still so we decide to stroll beyond these streets and turn the corner from San Antonio Abad onto Avenida Indepencia, the street by which the procession will enter the city. It’s then we catch our first glimpse of the profound magnitude of this celebration.

As far as we can see, the streets are festooned with purple and white balloons, paper flags etched with the image of Jesus, purple and white crepe paper flowers on palm fronds, flowered archways spanning the entire street for what looks like miles. People line the sidewalks, lean against walls, clamber onto rooftops, sit in doorways; whole families wrapped in blankets watch from balconies. Religious-themed murals made of flower petals, coffee beans, chamomile, seeds and sawdust lay like carpets along the path the procession will take. Swaying palm leaves adorned with yellow, red and white paper flowers line the roadway.

And then the sun crests the mountains that ring the city, glances off the domes of Las Monjas and the Parroquia, falls across the brick walls, the people lining the streets, the painting of Jesus in his crown of thorns; it warms the face of the old woman in the street standing alone in her white shawl leaning on her cane. In the hills, the sun highlights the purple blush of jacarandas across the city, all in full bloom now.

And in the distance, we see the first signs of the procession; thousands of pilgrims slowly walk toward us down the flower-scattered pathway, led by a priest swinging his censer and children in white and red robes following solemnly behind. Young girls in white dresses with purple satin sashes and feathered white angel wings walk silently behind them, heads bowed.

Then we see the pilgrims, those who have walked all night in silence, women wrapped in shawls and scarves, men and boys carrying tin lanterns on poles, other men dressed up as the Roman soldiers who wrestled Jesus to the cross where He was to be crucified. And finally, the bloodied Nuesto Señor de la Columna leaning in agony over the column (said to have been crafted from corn stocks and orchid bulbs), followed by a purple star-cloaked Mary, then John, the disciple who was thought to be the closest to Jesus, all of them carried on biers by weary pilgrims. Some of the faces are creased and worn, some imbued with joy. Tears stream down the cheeks of many. In all of the faces, though, the story that is most profoundly written is the story of their powerful and unrelenting faith.

As the procession passes, the women and men and children who have been watching step into the path and join the procession. The stream of people has now become a river. And we do the only thing we can do: we join the procession too. As we turn onto San Antonio Abad toward the church of San Juan de Dios, the streets and hills and church domes of San Miguel are flooded with the first early morning sunlight. The sacred carpet murals are demolished now from the tramping of thousands of feet and air is sweet with the smell of crushed chamomile, fennel and flower petals.

We reach a turn in the road and the procession stops. Beginning softly at first, then rising, comes the sound of singing. It is a group of men, mostly older men, men in straw cowboy hats, men in baseball caps, men with jean jackets and backpacks. Men singing. And in the distance another group begins, old women in rebozos, young women carrying babies, women in aprons. Like the just-risen sun falling in gold bands across the green hills, the sound of singing is light and full of hope.

As we wend our way through the crowd and veer off toward one of the side streets in search of an early morning coffee, the procession reaches the plaza of the church of San Juan de Dios where a mass will be held. We know the procession has reached its final destination because all the bells in all the churches of San Miguel have begun to ring, a wild, unbridled cacophony of sound. A sound so sweet, so raucous and full of joy, it is as though the very hills themselves are singing.