A Mexico cookbook by David Sterling

© 2014 by the University of Texas Press, used with permission)

The Canadian author and Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro said that “The constant happiness is curiosity.” If this is the case, then chef and cookbook writer David Sterling must have taken great joy in putting this book together, for it reflects tireless research that was surely driven by an intense desire to learn as much as possible about the cuisine and the culinary traditions of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

One of the University of Texas Press’ William and Bettye Nowlin Series in Art, Culture, and History of the Western Hemisphere, which includes Diana Kennedy’s Oaxaca al Gusto, Sterling’s 2014 book may well be considered the definitive work on the foodways of the Yucatan.

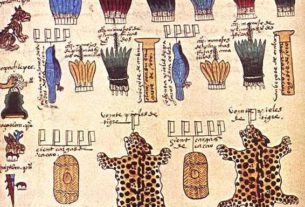

The reader is given some helpful contextual information on the history, geography and cultural background of the region, followed by a fascinating and beautifully photographed section on Yucatecan ingredients. (Seventeen different photographers contributed to this book, and individual photos are credited with the photographer’s initials.)

Fruits, vegetables, beans, grains, seeds, chiles, spices and herbs are all covered in this part, which includes some typical Mexican ingredients, as well as those particular to the Yucatan. The botanical, English, and Mayan names are provided, which is extremely helpful, since nomenclature is one of the sticking points in looking for regional ingredients.

Vivid descriptions and photos present insights into the food that comes from the monte, or forested outback, inhabited by the wild turkey, tapir, deer, peccary, and other indigenous species. Recipes for roasted quail and rabbit ragout are particularly appealing to modern sensibilities.

A look at the food and lifestyles of the present day Maya is shown in sections on the milpa, or family field, and the solar, or home garden and yard. While the triumvirate of corn, beans and squash — sometimes called the Three Sisters — has traditionally been planted in milpas by indigenous farmers in many regions of Mexico, the Yucatecan versions of corn-based dishes are significantly different from their counterparts in other regions of the country.

In these sections, Sterling introduces us to locals he has befriended and who have taught him more than recipes. Engaging photographs of the people and their homes draw the reader into an intimate look at the household and the way its food is derived, from planting to table. Although corn is grown in the milpa, its labor intensive preparation is carried out in the solar.

Soaking and cleaning the corn, then grinding and forming it into masa for tortillas and other foods, has traditionally been the work of indigenous Mexican women, and the recipes given in here are characteristic of the Yucatan, using typical ingredients such as chaya, the leaf of a small bush and a regional staple, and squash seeds, used as filling in different types of tamales.

The author also takes us along the peninsula’s coast, dotted with fishing villages whose harvest from the sea adds to the agricultural harvest to enrich the Yucatecan diet. Besides the great variety of fish and shellfish, there are coconut palm groves along the coast, and in one recipe the two are combined to make Langosta con Leche de Coco, a recipe for lobster tails poached in sweet coconut milk. A recipe for Camarones al Mojo de Ajo — shrimp in garlic citrus sauce — differs from other regional recipes for this dish in that it adheres strictly to its Cuban origins, using the typical Yucatecan ingredient of Seville, or bitter, oranges, where most recipes use lime.

Besides the Cuban influence, there is a French aspect to the Yucatan’s cuisine, most obviously reflected in the bakeries, where loaves of pan francés, with crisp crust and a soft center, are frequently made with a strip of banana leaf inserted into the characteristic center slit of the loaf. Recipes for this and other baked goods are given in La Panadería, a part of the book’s section called The People’s Food, which — in addition to the bakery — includes La Chicharronía. Here lard is rendered and pork belly and organ meat are fried and scooped up in tortillas to make impromptu, but highly appreciated, tacos.

Also in this section are La Comida Callejera — a tempting look at the food and drink sold at food stalls in the market and stands on the street — and La Cocina Económica, food of the small, family owned restaurants selling comida, the big, afternoon meal consumed throughout Mexico. These meals are not only economical, but fairly quick and easy. The most easily prepared recipes, for simple but tasty dishes such as meatballs, chicken and cutlets, are found here.

La Cantina, that iconic Mexican institution, has seemingly undergone the same changes it has in the rest of the country, with many of them evolving from male-only dominions to family friendly drinks-and-appetizers places, sometimes with a full menu. This last part of The People’s Food gives recipes for Yucatecan margaritas, made with mezcal, as well as some regional cocktails and light, appetizer type dishes, some of which, such as the chicken livers in tomato sauce, could be served as main dishes.

Sterling takes us to the urban centers of Campeche, Merida and Valladolid, hubs of commercial and cultural activity. Here the Maya and the Europeans, including Spanish, French and Lebanese among others, have exchanged knowledge, goods and recipes. Descriptions of these cities are filled with information on the histories that have formed their unique characters. Recipes associated with each city are given, from Campeche’s famous shrimp and oyster cocktail, now served all over Mexico, to the distinctly Lebanese kibi, or meat and bulgur patties, of Merida and the old Spanish recipes of Valladolid.

The next part of the tour goes through some of the beautifully photographed pueblos, or small towns, scattered throughout the peninsula. Subjects as varied as beekeeping and pit cooking of pibil dishes are discussed here, and recipes are given for both every day and festival dishes of the different pueblos.

The unique smoked taste of Yucatecan food, and ways to achieve it in home kitchens, is explored. The recipes for recados, or seasoning blends, essential to several of the recipes given throughout the book, are given, along with salsa and masa recipes. There is a list of resources for obtaining most of the harder to find ingredients.

This is not a book for the novice cook, although many of the recipes are not difficult, especially those in the Cocina Económica section. However, I would recommend it to anyone, whether a cook or not, who is interested in the history, geography, culture, foodways and people of this fascinating region of Mexico. Enormous in scope, the book has something for everyone, and armchair travelers will delight in the journey.

Being a food writer, I was naturally most interested in the recipes and their histories and sources, and found many that translate well into the non-Yucatecan kitchen. Two that do this especially easily are Chayas Fritas, where spinach makes a very good substitute for chaya, and Sorbete de Coco, which can be made with canned coconut milk. Both recipes are provided courtesy of the University of Texas Press. The book is available from Amazon and the University of Texas Press.

- David Sterling’s sautéed chaya with smoked bacon: Chayas fritas / Tsajbil chaay

- Yucatecan scrambled eggs with eautéed ehaya: Huevos revueltos con chaya / Chay-he’

- David Sterling’s Mexican coconut sorbet: sorbete de coco