Good Reading

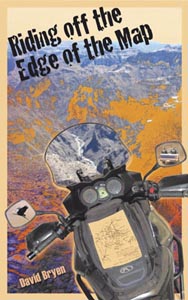

Riding off the Edge of the Map – A Mexico book by David Bryen

Dancing Heron Press, 2013

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback

Do you remember that best seller several decades ago, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, in which author Robert Pirsig details (but gets lost in digressions) a motorcycle trip from Wisconsin to California? David Bryen’s new book, Riding off the Edge of the Map, is a much better book, detailing (and reflecting upon) a far more fascinating motorcycle trip — through Mexico’s Copper Canyon.

Do you remember that best seller several decades ago, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, in which author Robert Pirsig details (but gets lost in digressions) a motorcycle trip from Wisconsin to California? David Bryen’s new book, Riding off the Edge of the Map, is a much better book, detailing (and reflecting upon) a far more fascinating motorcycle trip — through Mexico’s Copper Canyon.

As David and Gloria, his lovely wife and companion for 38 years, were moving into their newly built home in Ajijic, from a few doors down David heard the old familiar roar of a motorcycle; and following that noise like a bug toward a street light at night, he met Jake, with whom he “dropped into an immediate brotherhood” because of their shared passion for motorcycles.

A few weeks later, David and Gloria were barely settled in when Jake invited David to join him and a Canadian buddy, Tom, for a motorcycle adventure, “into Mexico’s wildest country, trying to get to the legendary vistas of Copper Canyon (Barrancas del Cobre) on ‘roads’ traveled only by indigenous Tarahumara and local Mexicans….” Jake was 52, and Tom and David were 62.

Neither the men nor their bikes were in perfect condition. Before the trip began,, Tom informed them: “Two years ago I flipped my car, landed on its top and broke my neck. Three years ago I had a hip replacement, so whatever we do, I won’t ride on the dirt.” Jake admitted, “Every year I plan a big trip on the motorcycle. Last year I had to cancel my trip because I burned myself very badly when a paint can exploded in a burn pile…. I couldn’t go the year before because I had a stroke and didn’t recover in time.” Tom’s running lights did not work, “his antilock brakes were malfunctioning,” and his rear tire had little tread. David, a motorcycle safety instructor, worried that “macho impatience trumped safety.” Shortly into the trip, David’s own headlights “had begun to randomly turn off.” Jake and David were expert riders, Tom was not.

Copper Canyon is actually a series of canyons. “The Barrancas are extremely rugged and cover some 25,000 square miles, more than four times the area and 1,700 feet deeper than Arizona’s Grand Canyon.” Magnificent yes, but the author, “Assailed by its grandeur… was also blinded by its treachery.”

A few days into the trip, David found himself “underneath my smashed bike waiting for my two riding partners… [with] broken ribs, a two day ride from medical services, on nearly inaccessible roads, in territory crawling with violent drug traffickers, and in a country whose language I’d only begun to learn. We’d been lost for two days, had no way of knowing how to get where we wanted to go, kept thinking that the roads had to get better, and were too frightened to go back over the rocks, rivers, canyons, mud, and mountains we had crossed coming in.”

For David, the trip was both an intense outer journey and an intense inner journey. For either, intense focus is necessary. “The attention demanded every moment while riding is one of the reasons that I love to ride. I can’t be anywhere else.” Likewise in those moments, he can’t be anyone else.

David had spent decades as a professional therapist, a careful observer of human relationships, including his own, and he had worked hard to develop the ability to identify and reflect upon some of the hidden issues we struggle with as human beings. Looking at the conflicts between the three travelling companions, one of whom was himself, he remained aware of how difficult relationships between men can be. For example, “Giving and accepting advice is tricky for men. It seems the Alpha Dog competition never really leaves us, and asking for help violates a primal fear of inadequacy. Fears of holding each other back, being left behind, and not being able to run with the big dogs, are other male diseases.”

What began as a pleasure trip metamorphosed into something else: “The highway had deteriorated from asphalt to terror.”

Incidentally, under each chapter title is an appropriate and provocative quotation. Here is one by Joseph Campbell: “What is required of us is that we live the difficult and learn to deal with it. In the difficult are the friendly forces, the hands that work on us.” In the paragraphs that follow, David reflects that “Riding and successful therapy parallel each other at this point. When clients become aware and break the automatic and unconscious reliving of the past drama and bring their attention to the here and the now, they’re free to make choices.

Readers will also be moved by the Mexican family that rescued David and in their old Ford truck carried both him and his bike to Morelos: “Though relieved that the pickup was filled with a family, not drug runners, my hope faded as I watched nine people pour out of the cab…. [but he] relaxed a bit at the warmth in their generous smiles.”

On the road to Morelos, the driver stopped at a favorite vista. Standing at the edge of the road, near the edge of a cliff, he spread his arms toward a particularly beautiful valley. “He reached into the cab, turned off his music to experience the silence…. We all basked in the splendor of this valley filled with V-shaped canyons and ridges that seemed symmetrically staked all the way to the sky…. It was as rugged and green as any rainforest.”

At that moment David realized that he and they belonged to “the same misty-eyed tribe” and that “Their wonder in the face of nature’s beauty was identical to mine and they swelled in pride that this dirty, mud-caked white guy swooned at the beauty below.”

In later reflections the author concludes that “The drive to find oneself in such mystical experiences of beauty is at the core of every human being.” “And even though it may lead to his destruction, “Every time the Sirens call, it seems worthwhile… at least for a moment.”

A remarkable book, for both men and women.