City parks were not an important part of my life when I was a child. I was raised in the country on a farm which, for all practical purposes, was a park. Growing older, though, I learned to appreciate the importance of city parks, especially in large urban areas. In fact, I wound up residing in an urban area myself. I discovered that on a hot day in the city, stepping into a forested park was a pleasant feeling. There was actually a noticeable drop in the temperature!

For a big city, a park provides a welcome change of pace, a respite from the concrete jungle while the trees provide much-needed oxygen. An urban park is a meeting place and social space for civic, cultural and economic activities. There is a real need for parks in urban areas.

Some city parks have become quite famous, such as Central Park in New York City or Hyde Park in London.

Mexico City boasts a first-rate urban park known as the Bosque de Chapultepec, or Forest of Chapultepec, a destination for both international tourism and local recreation. Chapultepec is a living historical monument to major developments in the history of Mexico. And it’s popular, receiving about 15 million visitors annually. Formerly on the outskirts, the park is now surrounded by Mexico City, which makes it even more valuable as an urban green space.

When my wife and I took our boys on their first visit to Mexico City, we had to include Chapultepec on our crowded itinerary. How could you visit Mexico City and not spend at least a day there?

When possible, I prefer to either walk or take the subway (Metro) in Mexico City. Conveniently, there are a couple of Metro stations located at entrances to Chapultepec Park. So that’s how our family arrived to the park.

The Bosque covers just over 686 hectares, which for those of us who think in traditional English measurements, is 1,695 acres. It is full of trees, including the Moctezuma ahuehuete and about 40 other species. Depending on the time of year, there may be from 40 to 60 bird species in the park, since many of them are migratory. Our boys had an encounter with a squirrel.

The Bosque de Chapultepec has trees, paths, statues, fountains, monuments, small lakes, an amusement park and a host of vendors selling their wares.

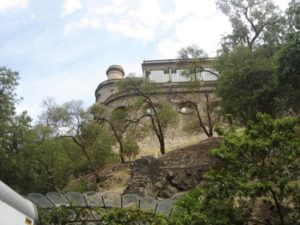

Towering 200 feet above the forest is the hill, made of volcanic rock, called “Chapultepec.” That means “Grasshopper Hill” in Nahuatl, the language spoken by the Aztecs and kindred peoples.

The section of Chapultepec most-visited by tourists is the eastern portion, including the hill, the zoo and museums. Other parts of the park are more popular with local residents seeking some relaxation. Another sector, not accessible to the public, includes Los Pinos, the Mexican presidential residence.

The Bosque de Chapultepec is full of history. Archaeological remains date back to the pre-Classic period, which in Mesoamerican history, means before 250 AD. Later remains of the Toltecs, the mysterious Teotihuacan culture, and the Tepanacas have been discovered.

The Aztecs arrived in the thirteenth century and settled in the region. After becoming powerful, they used Chapultepec as a retreat for their rulers, a place of religious rituals, a repository for their rulers’ ashes, and a water source for their growing capital city Tenochtitlan, the nucleus of what is now Mexico City.

In 1521, Grasshopper Hill was the site of a battle between the Aztecs and Spaniards, and after the Spanish Conquest (1519-1521), the commanding heights of Grasshopper Hill were utilized by the Spaniards. In the 1700s, a castle was constructed at its summit. This castle has been modified and used for various purposes throughout the years and is referred to as Chapultepec Castle.

After Mexican independence, Chapultepec Castle became a military academy. It was serving in this function in 1847, during the U.S.-Mexican war, when it was besieged by the U.S. Army. Some of the cadets and an officer refused to surrender and perished in the battle. These six are known in Mexican history as the Niños Héroes, or Boy Heroes.

Later in the 19th century, the castle was the residence of the Emperor Maximilian and the Empress Carlota (1864-1867) and later of Porfirio Diaz, who ruled in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Now the castle houses the Museo Nacional de Historia. The castle is worth a visit for the exhibits, the view, the garden, and the building itself.

Chapultepec Castle was featured in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 movie version of Romeo and Juliet, as the Capulet mansion. In 1992, it was the site of the Chapultepec Peace Accords, which ended the civil war in the Central American nation of El Salvador.

Grasshopper Hill is the heart of the park. Around its base is the forest, with various sorts of trees and monuments.

Unsurprisingly, there are several monuments to the Niños Heroes. At the foot of the hill is the Obelisco a los Niños Héroes, constructed in 1880 and 1881.

A newer and more visible monument is the massive Altar a la Patria, inaugurated in 1952, standing at the park’s principal entrance. It includes six enormous columns, each representing one of the Niños Héroes, with a statue in the middle, all carved out of Carrara marble brought from Italy.

In a quiet, less-visited location along the base of the hill is the Tribuna Monumental, a memorial to the Escuadron 201, a Mexican Air Force unit that fought alongside US forces in the World War II Pacific Theater. The monument has the names of the unit’s members and contains the mortal remains of two of its officers who died in the war.

The most visited-part of Chapultepec Park is the Alfonso L. Herrera Zoo, with 5.5 million visitors annually. It has the typical zoo animals and our family enjoyed it.

Every zoo has its specialties. I recall a previous visit to the Guadalajara zoo, with its impressive nocturnal animal building. In Chapultepec, some impressive animal attractions include the eagles, and the panda exhibits.

The zoo currently houses three female giant pandas. All three are descended from the pair of pandas given to Mexico by China in 1975, part of the Middle Kingdom’s “Panda Diplomacy.” Since then, eight panda cubs have been born in the zoo. In fact, Chapultepec Zoo is the first zoo outside of China, in modern times, in which a panda cub was born, and the first in which a panda cub was born and survived.

Also in Chapultepec Zoo, certain animal exhibits are sponsored by corporations, which are then allowed to place their company symbol on that particular exhibit. For example, the polar bear exhibit is sponsored by Coca-Cola, which makes sense considering the company’s use of the animal in advertising. Of course, the penguin (pingüino) exhibit was sponsored by the purveyors of Pingüino, the cream-filled cupcake produced by the Marinela division of Grupo Bimbo. I kid you not!

The Bosque of Chapultepec has a number of museums, but on our visit we only got around to two of them. We visited the aforementioned museum in the castle and the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, one of the world’s finest archaeological museums. The latter is Mexico’s most-visited museum, with over two million visitors a year.

The anthropology museum showcases artifacts of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures of Mexico. There are galleries for various cultures and cultural regions, for example, a Maya room, a Toltec room, and so forth. The biggest gallery is the Aztec room, which contains the famous Solar Stone and many other artifacts. The second floor exhibits are dedicated to the Mexican indigenous cultures of today.

One structure in the Bosque de Chapultepec you could easily pass by, but is worth a visit, is the Fuente de Netzahualcoyotl. Dedicated in 1956, the fountain commemorates Netzahualcoyotl, a 15th century ruler of the city of Texcoco (now part of Mexico City). The fountain portrays stages in the life of the ruler, who was also a poet, an engineer and a philosopher.

What can I say? There is plenty more to see in the Bosque de Chapultepec, a park beloved by tourists and locals alike. What’s the best way to appreciate it? Go there, climb Grasshopper Hill, descend and stroll through the park to see what catches your fancy.