A new exhibit running through January at the Museo de las Culturas Populares in Coyoacan, Mexico City, celebrates the “wow” factor of the wrestling phenomenon known the world over as lucha libre (free fighting) — that is as famous a Mexican cultural export nowadays as Frida Kahlo, Day of the Dead, and tequila.

It’s also big in Japan.

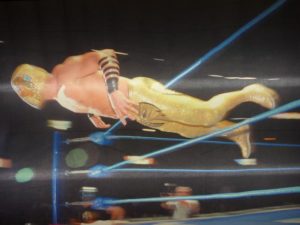

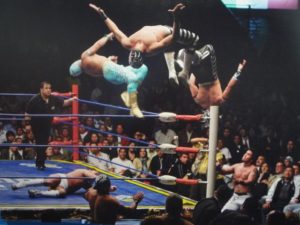

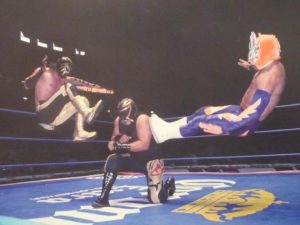

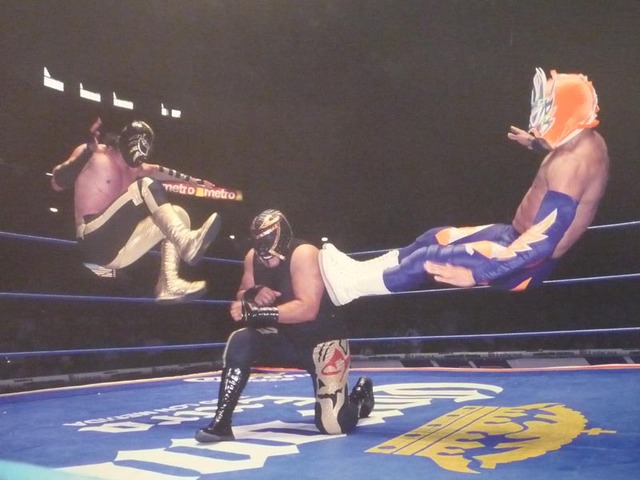

The sport, or perhaps more accurately “entertainment,” is characterized by its larger-than-life competitors, spectacular leaps into the air and various bone-crunching maneuvers, tag-team matches and, of course, masks. Lucha libre is perhaps best symbolized by the use of masks that have also become a favorite of artists and culture vultures everywhere. Lately they made a controversial stir in international headlines, as lucha masks were adopted as stage wear by the infamous Russian feminist punk band Pussy Riot. Noted for their bizarre depictions of animals, gods and ancient heroes, luchadores (wrestlers) guard their identities behind these disguises with a time-honored, paranoid relish, wearing the masks whenever appearing in public.

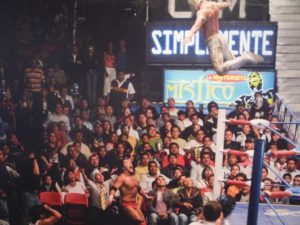

The exhibit, called Reflejos y Destellos Lucha Libre Arte y Espectáculo, is primarily associated with photography, and features large format images of such contemporary lucha heroes as Sangre Azteca, Angel de Oro, Místico, La Sombra, Rey Cometa, Super Crazy, and Rey Bucanero by photographers including Edgar Medel, Gonzala López Peralta, Marisa Castillo Lara, and Diego Gallegos. There are also pen and ink works on paper by Miguel Valverde Castillo, some paintings, and a video installation presenting interviews with wrestlers, crowd scenes, and the entrepreneurial spirit of street vendors outside the traditional lucha venue in Mexico City: Arena Mexico on Lavista Street in Colonia Doctores. Forerunners El Santo and Blue Demon are also honored along with Gory Guerrero, Huracán Ramírez, and Mil Máscaras, these legends of the ring helped cement lucha libre’s mystique by appearing in luridly bizarre wrestling movies in the 1960s.

On a historical level, lucha libre began as a 20th century phenomenon played in the provinces until the founding of the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (Mexican Wrestling Enterprise) in 1933 instituted a national code. The enterprising fellow behind this organization, Salvador Lutteroth, popularized the sport even more when television came along in the 1950s. El Santo, he of the silver mask, became the face of lucha libre, enjoying folk hero status and a career lasting 50 years. El Santo appeared in both comic books and movies in which he was just as likely to face off against Guanajuato mummies and vampires in shadowed cemeteries and haunted mansions as with mere mortal opponents under the bright stage lights of the lucha libre wrestling ring (“stage” being the operative word).

El Santo’s son has since taken over the profitable reins of his father’s legend; meanwhile many more performers have stepped into the ring to forge their own fierce followings. Now the super-inflated egos, the moves, the athleticism, the sex symbol status, and the competitiveness of personal battles and tag team matches have elevated the sport into the stratosphere of big bucks and hyper celebrity. Now there are female luchadores and there are gay luchadores. There are American luchadores and Japanese luchadores. But at its core it is Mexican. Lucha libre may now be said to denote much of the diversity now epitomizing modern Mexican society. This, in turn, symbolizes the manifesto of the museum in which the exhibit is currently on display.

The Museo de las Culturas Populares (Museum of Popular Culture) continues to be a crowd pleaser both for Coyoacán locals and visitors of all stripes and nationalities, consistently catering, as it does, to those aspects of Mexican culture enjoyed most by the “masses” — and highlighting the nation’s diversity in the process.

Many expositions of so-called fine or modern art at high-end galleries can oftentimes seem as alienating and lonesome as scenes in an Edward Hopper painting, and if a pin dropped you could certainly hear it land. Yet the Museum of Popular Culture is always pumping — in a respectable fashion, of course.

When something is put on, the people come because they want to see it. Here, all forms of art may be said to be equal, and none is more equal than others. The key word is popular, and if for some that translates as low, so be it.

The museum was opened in 1982, the result of the labors of anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla. It is conceivable that in some years to come, “street” or “graffiti art” may well be viewed in an anthropological context. For now, however (and at least for the last 25 years), this sort of art has grown in popularity apace with the burgeoning urban classes of the world — for better or worse. And while some would say worse, street art and the artists producing this work have gained more acceptance among galleries and even government bodies. To wit (and reflecting both types of concerns), a large wall to the rear of the museum has been handed over to local graffiti artists Saner and Sego, who have teamed up to create an ambitious, decidedly phantasmagoric work called “Dream Weavers.” It is hoped that this outstanding piece of wall art will remain a part of the museum’s visual dynamic for a long time to come.

Other prominent areas in the museum include the Chapel — a 19th century building that houses revolving exhibits, the central courtyard, Quinta Margarita, along with the Annex Moctezuma that separates the older building from the modern Sala Guillermo Bonfil Batalla out back (where the lucha exhibit is being staged), and a further series of Patios (Jacaranda, Central, and Moctezuma) — which are used for dances, book presentations and fairs and markets to compliment seasonal exhibitions (such as Semana Santa and Day of the Dead).

Come visit a Coyoacan institution, and roll with the masses.

The Museo de las Culturas Populares is located on Hidalgo 289, Coyoacán. Hours: Tuesday to Thursday 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Friday to Sunday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Tickets: 11 pesos; free admission under 12, over 60, pensioners, people with disabilities, students and teachers (with ID). Sundays, free admission.