Driving up the long rise into Mineral de Pozos, framed by the gray-brown humpbacked mountains once laced with veins of silver and gold, the visitor first sees the stone walls of the cemetery, the panteón, before he enters the town.

It seems like a fitting introduction to a city that nearly died itself, sinking from a population of about 75,000 in 1900 to only 200 residents fifty years later. It was not the plague that caused this decline, although it must have felt like it as house after house fell silent, as real estate became nearly worthless, as schools closed and civic life dried up. For a variety of reasons — the revolution of 1910, the flooding of the mines, the exhaustion of productive ore — the glory days were over.

In keeping with the Mexican view that death is only a part of life (the longer part), the above-ground tombs of the cemetery enclosure are as bright and as individual as the characters who occupy their narrow plots. Several have domed tops. Many are covered with decorative ceramic tile, like a kitchen counter or an upscale parlor floor. Others display elaborate cornices and stone balusters surrounding them.

The housing designs of the dead bow to no codes here. One feature many have are the tubes opening in the top to let in offerings of food, beer, or tequila on the Day of the Dead, where families gather next to the tombs and celebrate through the night. The fiestas of eternity can be just as raucous as any during the earlier parts of life, with music blaring and fireworks erupting. One advantage is that the partiers don’t have to get up and go to work the morning after.

One sadder feature of the panteón, because death is not recognized among the sadder features of existence, is that — like Pozos — it’s a ghost town in itself. It is less than half filled, and has gradually run low on customers. Standing behind the last row of tombs, I covered my eyes to study the weedy terrain leading all the way to the back wall. The plot had been laid out soon after 1900, when the future had a different look.

Driving into town, the first building that came into view looked fresh and recent in construction, although traditional in design, with a façade of irregular stone like that of the cemetery. Surrounding it were the ruins and broken walls of many others. Like an x-ray, these walls offer lessons in traditional construction techniques. Beneath the stucco, long fallen away, layers of mud brick, dissolving year-by-year back into the soil, alternate with narrow courses of stone.

The old roof beams are long gone, salvaged for firewood as the town shrank. Some months, Pozos can take on a notable chill at night, standing as it does at 7500 feet. In the complete absence of any new construction, at mid-century no further structural need could be found for the beams that remained on abandoned properties, but the fireplace beckoned in a compelling way.

This visit began to feel like an assignment to investigate the wreckage of a war-torn city in Germany in 1946, where the rubble in many quarters hadn’t yet been cleared. The same condition set the tone the farther I went, but then small stores (tiendas) began to appear, then a tiny restaurant. These were buildings covered to the weather.

In another block I stopped at a small plaza, the Jardin Principal. It had living trees, and at its edges women poked at improvised grills with roasting ears of corn still in their husks. Flat griddles held sizzling gorditas. Children chased each other, laughing.

At the far end of this hopeful square stands a classic limestone building that houses a hopping bar enclosed by walls papered with sepia images of old Pozos, the once prosperous Pozos, before its near death and incipient resurrection. But do not look yet for its remains up at the panteón.

Pozos climbs both slopes of a narrow valley. The term level is more easily found in the dictionary than along its cobblestone streets. The small Jardin Principal edges the main drag but drops away on both ends, so that a flight of stairs is need to descend from the opposite side. White walls capped with a red masonry crown frame the scene. An ornate wrought-iron bandstand in the center — still proud but rusting here and there, a survivor of the good days — suggests there are once again events to celebrate, gatherings that require a closer look to understand.

Isn’t that the case with most of Mexico? While this country is as seductive as a sailor’s dream, it never yields itself easily, especially to expats more used to Wichita or Washington. When I travel here, I leave my gringo eyes at home.

Descending from the plaza’s corner, I discovered an art gallery called Galería #6. As a painter, this always catches my eye, and I hurried toward the open door.

Inside, a series of white-painted rooms edging a garden were hung with photography and installation art. I was alone for a while until I was joined by one of the owners, a man named Nick Hamblen. He was willing to talk about what brought him to Pozos and how it felt to be a businessman in a recovering ghost town.

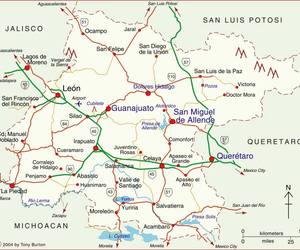

After leaving Dallas, Hamblen has lived in Pozos for three years, although he and his partner had started the business before that. It includes a bed and breakfast that caters mostly to a Mexican clientele, people looking for a brief escape from Mexico City or nearby Querétaro, although the gallery is aimed more at American and Canadian visitors. It features painting about 70% of the time, with the balance of the shows going to photography. The business has three full-time employees.

“How about land titles?” I asked, after he said they owned the building they were in. I was imagining city lots abandoned for generations. Uncollected property taxes could be another issue, although the deteriorating city had long ago come under the rule of the municipio of San Luis de la Paz, ten minutes away.

“Fortunately, there are established means to deal with that,” he said. The title on the gallery and land we were standing on had been clear, not the usual case.

“Even when title claims might be based on anecdotal evidence?”

He agreed. The city hall had burned in the 1920s, destroying all the official property records. Residential plots were already being abandoned for lack of buyers by that time.

“What is it about this place?” I asked him. It may have taken him by surprise. “As I look around here, the force, the weight, even, of all these ruins, all this disastrous past is simply inescapable. I see the new growth developing all around, but the matrix of the city that supports it is decay. What am I not seeing here that makes Pozos a good fit for someone like you?”

Nick Hamblen has the look of a guy who is comfortable in his own skin, although it may have taken him a while to get there. Isn’t that the case with most of us? Yet many people never arrive on that path, although I’ve often speculated that Mexico may be one of the best places to undertake the journey.

“It’s the rhythm here,” he said, with a gentle but knowing smile. He went on to explain the process of unwinding day by day over three years, and still having some distance to go. He was clearly enjoying the process, and had no problem with the fact that the end was not in view. As for the absence of many expats to provide company and support, Nick is clear that he never wanted to recreate his Dallas life here.

One of my destinations in Pozos was an eight-room hotel called Posada de las Minas. It’s on Calle Manuel Doblado, a long uphill block from the plaza, and it edges a street that ultimately leads up to the old mines beyond the edge of town. I had heard of it in San Miguel, where I live.

It had been characterized as the archetypal restoration of an old and spacious nineteenth century mansion, literally the townhouse of a family who owned extensive agricultural property. They didn’t come from mining money, and as the town declined, they had walked away like most others, retreating to their haciendas and their pampered horses.

The current owners had knowingly bought a colossal ruin that possessed three firm arches standing at the back of the foyer, dominating the rubble-filled courtyard below and still making a statement, but the rest was, well, look at the before and after pictures here that they graciously furnished.

I can understand their interest, having restored two Victorian houses myself in Saint Paul, but they both still had floors and roofs. Even windows and doors. Plumbing and wiring. You see how it goes.

Julie and David Winslow were prepared for my arrival. The principal question in my mind was how they came to decide to make a major commitment of time and money to open a small boutique hotel in a town like Pozos. And it clearly wasn’t only money, it was taste. The after photo gives the general impression exquisitely; Julie’s flair for decor is evident. The sense of detail is obvious in every room, every corner.

“So,” I said to them, after we sat down in a long room facing the street. As we’d gone in, David had remarked that this room was once, in later years, a shop. Selling what? Groceries? Now it offers his own stunning photos of a town and countryside that would bring any photographer to his knees. “So,” I repeated. “How did this happen in a town without many expats as a support group?”

There are probably between twenty-five and thirty,” David said.

The Winslows already owned a condo in San Miguel in the ’90s. When a friend’s ashes were scattered over the ruined mines in Pozos, an idea that must have had a thoughtful symmetry, they decided to check it out. It charmed them both.

On one of the first two properties they bought they built a house. Naturally, the same title issues confronted them. New owners often encounter people showing up after the construction has begun claiming that the land is theirs. David feels that the use of a notario will usually clear any obstacles of this kind. This title includes powers beyond those granted to a notary in the U.S.

The mines themselves, where the surrounding hillsides are often separate from the processing haciendas, are often still a battleground of unresolved title issues.

Utilities are another concern. Water has been an ongoing problem, and even though the Guanajuato state government built a dam some years ago, no pipeline was ever completed to bring the water into Pozos. While there is a recently constructed electric plant not far away, service interruptions are not unusual, especially — for some reason — on Friday evenings or after rain showers. The hotel’s water pressure depends on a tank mounted on the roof, but without power, the pump is unable to maintain enough volume. With its own gas tank, the kitchen is able to continue cooking under these conditions, and it can become a little like camping out in great comfort. Think of candlelight in an exquisite mansion.

The Winslows maintain an attitude of ironic resignation through these problems. Their hotel is gorgeous, an obvious destination for visitors from all over Mexico, and it amply reflects their care for detail and their skill in management. The food in the restaurant is excellent and the service attentive. The hotel offers a full service spa and fitness center with a pool.

There is interesting shopping in Pozos in the areas of décor, clothing, jewelry, and crafts. Nick Hamblen’s Galería #6 offers art as good as anything in San Miguel. Kicking back in the hotel courtyard, listening to the caged birds settling in, you can feel your pulse and blood pressure returning tick by tick to a more civilized and untroubled level.

And then there are the mines themselves, the failed linchpin of this city caught in a snapshot of seemingly unstoppable rebirth. I couldn’t help but feel the sense of building momentum, slow but undeniable, as I drove up the hill past the roofless skeleton of a state-of-the-art school of the late nineteenth century. Even in this ruined condition, its optimism is still evident. The last hundred years had only been an intermission, not an endpoint.

The grand ruined structures of the mines and their processing haciendas above are as silent as the cemetery was coming in. This was big business in its day. No mud brick construction was used here; the best stone and finest concrete were the standard when building for the ages.

Even now, when all the roofs are gone, the walls still reach to the sky, to the future.