Good Reading

A Mexico book by Bruce Stores

iUniverse, 2009

iUniverse, 2009

Available from amazon.com (In Hardcover and Paperback)

For years, I have been curious about “the isthmus,” or more formally “The Isthmus of Tehuantepec,” perhaps in part because Frida Kahlo loved so much the traditional clothing of this rarely visited section of southern Mexico, or perhaps because I love the Zapotec rugs that come out of those indigenous communities. Indeed, the Zapotec language is the common tongue. The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is “without a doubt strategically significant as it provides a narrow land bridge between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. But it is nowhere near Mexico’s major cities or the beaten tourist track.”

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is that narrowest part of Mexico, where the distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean is shortest, 125 miles. The isthmus actually runs north and south, with the states of Tabasco and Chiapas east, and the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca west.

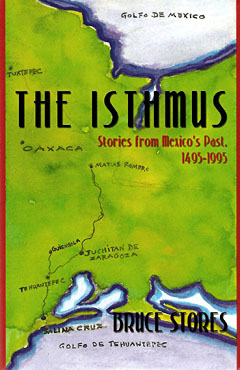

Bruce Stores has given us a very interesting book about this region, The Isthmus, Stories from Mexico’s Past, 1495-1995.

I picked up the book, looked at the attractive cover, and thought, wow, 350 pages of history about the isthmus is more than I want to read.

In fact Stores makes it simple. He gives us eleven chapters (followed by an epilogue), each of which is about one segment of Isthmus history that either had particular significance or is of contemporary significance to us. Here they are:

- Chapter One The Final Years of Binni gula’sa’ 1495-1519

- Chapter Two The Conquest 1519-1564

- Chapter Three Haremos Tehuantepec: The 1660 Rebellion 1660-1661

- Chapter Four Gregorio Meléndez 1810-1853

- Chapter Five The French Intervention 1861-1867

- Chapter Six Che Gómez 1905-1964

- Chapter Seven Baptism by Fire: Juchitán Students in Mexico City 1967-1968

- Chapter Eight Stirrings of Political Change 1968-1974

- Chapter Nine PRI Strikes Back 1977-1978

- Chapter Ten COCEI Rebounds 1978-1981

- Chapter Eleven The Free City of Juchitán 1981-1983

Stores then presents the historical material through a series of stories. It is a work, the author acknowledges, of “historical fiction.” For me, because I love stories, the history then became fascinating.

To further smooth the way, Stores focuses on the most indigenous town, Juchitán, rather than on its rival, Tehuantepec, which is depicted as a largely Spanish city, exercising (for centuries) power over Juchitán. The struggle for power is at the heart of the book: “A reoccurring theme in this 500-year history of Isthmus natives has been their continuous struggle for local control of their land and its resources.”

Along the way we also pick up interesting historical curiosities: “The commonly used term in Mexico, ‘Zapoteco’ is a Spanish adaptation of the Aztec wording, Zapotécatl, which means in the Aztec tongue, ‘another type of Indian.'”

The first chapter, “The Final Years of the Binni gula’sa’ 1495-1519,” begins by introducing us to a beautiful young woman, “Chitugui’ (yellow bird)… grinding maize on a metate,” but soon we discover that the Binni gula’sa’, like so many indigenous communities, is about to be attacked by the much more powerful Aztecs (who live far to the north) to provide living bodies to sacrifice to their war god, Huitzilopochtli. When the people of the isthmus resist, the Aztec ruler first sends warriors disguised as merchants to determine their military strength and later a complete army to attack the Binni gula’sa’. In the course of the story, a talented young warrior — now a general because of his services to King Cosijoeza — falls in love with Chitugui.

By Chapter Seven — “Baptism by Fire Juchitán Students in Mexico City 1968” — we are well into modern times. Here we meet two students from the isthmus, Alberto and Emilio, who are in Mexico City to study at the University, but who find themselves pulled into the political movements that preceded the 1968 Olympic Games, which culminated in President Díaz Ordaz ordering police and military forces to fire on the thousands of students gathered at the central plaza:

“Coming to the aid of the police were military forces. They were equipped with armored cars and tanks. The forces surrounded the square and sent live rounds of machine gun fire directly into the crowd, hitting not only the protestors, but also others who were present for reasons unrelated to the demonstration. Demonstrators and passersby alike — including children — were hit by bullets. Mounds of bodies soon lay on the ground. The killing continued through the night, with soldiers operating house-to-house sweeps in the apartment buildings adjacent to the square. Witnesses to the event would later claim that bodies were removed by garbage trucks.”

Throughout The Isthmus, stories incorporate historical fact with tales. We learn not only part of the history of the isthmus but of the whole nation as well. We discover aspects of historical personalities that have been forgotten. These days, the thing to do is to hate President Porfirio Díaz and to blame him for all things that went wrong for Mexico… the man who caused the Mexico Revolution that began in 1910. But in Chapter Five, “The French Intervention 1861-1867,” we meet a young Porfirio Díaz, who in fact was a hero in the war against the French and in that difficult time a man much admired by the citizens of Juchitán and Tehuantepec: One Juchitán soldier tells us,

“There on the outskirts of Puebla, General Díaz would sometimes lecture the young soldiers under his command with the aim of inspiring them to greater achievement. ‘Mexico is our country and what a great future we will have! We are proud to be Mexican and to live and die for our Patria,’ he would say to the enlisted men. At other times the young general would talk at length about his past. He told them how he grew up under difficult conditions in a mestizo (mixed Indian/Spanish) family. He was born to a lower middle class family in Oaxaca city in 1830. His father died of cholera when Porfirio was only three years old. He was forced to learn different trades as he was growing up. ‘This was how my family survived,’ Díaz told his men. He first learned to make and repair shoes.”

Just as President Díaz is vilified by so many in modern times, Juárez is almost universally loved as Mexico’s favorite President (who ironically was able to remain in power through the military victories of Díaz). But when the Indians of The Isthmus tried to recover their traditional salt mines for their own use (seized by outsiders) and to use their traditional land (seized by outsiders beginning with Cortez himself), and to elect their own public officials, Juárez, then Governor of Oaxaca (and himself a pure Zapotec Indian), ordered a force of 400 men along with some light artillery “to restore law and order in that rebellious town and to imprison its leaders.” When Juárez’ soldiers finished torching the town, one-third of Juchitán lay in ruin.

What are some weaknesses in Stores’ book? The Mexican revolution that began in 1910 — one of the most significant events in Mexican history — is largely ignored, yet in the long final Chapter Eleven, “The Free City of Juchitán 1981-1983,” much of the focus is upon the young Alejandro, a political activist, discovering he is gay, falling in love with Sergio, another political activist, and then revealing to his father and friends that he is gay. We then are given very conventional insights about gays. To me it was out of place in a book that up to the final chapter is about the political history of the isthmus, and to some degree of all of Mexico: indigenous people resisting far more powerful indigenous people, then the even more powerful Spanish, French (defeated by the indigenous people on The Isthmus in a battle known as “Cinco de Septiembre 1866”), and then other more powerful Mexicans, in order to control their own destiny, their own territory, their own town. Although it might have developed as a short story separate (or even novel), in this book it is a distraction and a disappointment to find this focus in the last chapter. A sympathetic listener tells the young man these platitudes, “‘Alejandro, please listen to me. Being gay isn’t the stigma it once was. People everywhere are taking a fresh look at it. The medical professions, educators, governments, even theologians are beginning to see sexual orientation in a different way. We’re in the 1980s now. Besides, you’re not a bad person just because you might be gay. That’s the truth Alejandro. Believe me. That’s the honest truth.'”

The Isthmus begins with the indigenous community of Juchitán preparing its defense against the imminent Aztec attack, with dialogue like:

“Ah, look,” one of them said. “Look up there. The king’s going to speak to us.”

Then, Cosijoeza addressed the gathering.

“Sons of the god, Gubidixa, the sun god of the Binni gula’sa’, hear my words. Consider them carefully!

“It will be here on this mountain that we will re-build our fortress. …Here on this spot the mighty Mexica army must be defeated. Take my word for this: victory will belong to the Binni gula’sa!”

How strange for The Isthmus to end with a chapter containing dialogue like this:

“Dad, can we talk for a minute?”

“Sure Alejandro. What’s on your mind?”

“This is something a little delicate Dad.”

“That’s okay, Son. I’m always open to talking with you about anything.”

For the most part I enjoyed Bruce Stores’ book The Isthmus, Stories from Mexico’s Past, 1495-1995. You will learn a lot about a little-known region, and a lot about the history of Mexico.