The Months of Mexico

I tell my friends that the only thing I have had stolen by Mexicans was my unwavering fealty to Canada: I have even considered living full-time in Mexico.

We are approaching the border crossing about half a mile off. There are no distinctive markings to the terrain to define it. There is no checkpoint. No armoured guards. No turrets atop outpost observation towers. Just a road sign signifying the end of America — well, the end of an American highway and the beginning of Mexican pavement.

So why am I edgy? I flick off the radio. Clear my throat. Is that a tremble to my hand?

“You’re making me nervous,” Vera says. “Relax. We’ve done this a thousand times.” Perhaps my unease was caused by our decision to take the Nogales city route to enter Mexico. In the past, we had taken the highway from Nogales, USA, and traveled the autopista to the official check-in a few miles down the road. No hassle.

However, taking the route through town could present a challenge or two. And it did.

The signs pointing us to Hermosillo, the first large center in Sonora State, started to peter out. They seemed to shyly diminish in size until, submitting to modesty, they disappeared altogether. Could it simply be a mistake, a Mexican shrug of the shoulder. (Let them find their way!) Or could I be lost.

“You’re lost,” Vera said, her fingers fumbling with the well-creased map of Mexico.

“No,” I said. “We’re lost.” I added smugly, “You’re the navigator.”

The rest of the conversation smoked up the windshield and is unprintable, but, like an Obama speech, indelibly imprinted in the memory archives.

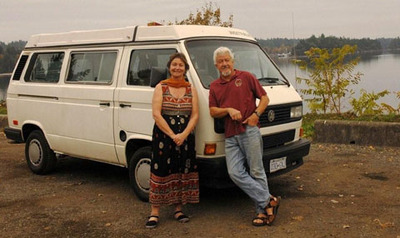

But we weren’t lost for long, for an angel arrived. It was not in the guise of the official highway angels who roam the autopistas and libres with their tool boxes and goodwill to assist broken-down travelers. This angel was just an unofficial good guy. In an unselfish act the type of which we have been beneficiaries in the past and undoubtedly will enjoy again during our travels in Mexico, an observant and generous motorist who obviously sensed our confusion pulled abreast and motioned to us. We followed and, por supuesto and voila! we soon spotted the elusive Hermosillo sign. Our insta-friend peeled off, and Frida — the Westfalia van that accompanies us everywhere during our months of Mexico and whose hero is the art maven Frida Kahlo – tooted an appreciative adios as we sped from the cobblestones to the pavement leading south.

Despite Vera’s exaggeration we have gone through the process of entering Mexico only a couple dozen times and although the customs process sometimes can be daunting, we’ve usually found that aside from some annoyances, mainly bureaucratic paper reshuffling, it’s not to be anticipated with too much dread.

My discomfort with border crossings also must be reluctance on my part to undergo questioning. Do you have this? Any of that? Where are you going? What is the purpose of your visit? Or it could hark back to our travels years before in Europe and Asia when crossing frontiers, such as into Afghanistan for example, was complicated by unnerving considerations such as cholera epidemics, graft, dysentery, physical threats and even crazy Russian truck drivers. (But that’s another story.) In truth, crossing into Mexico by road usually is quite pain free, except for that ceaseless photocopying.

One of my more memorable entries into Mexico was debarking from an Aeromexico flight from Vancouver, B.C., to Puerto Vallarta. This was in an era when the booze flowed freely (and was free en route), when hosts were still known as stewardesses and their smiles were genuine and when airlines departed and arrived when they said they would.

I don’t drink on flights, except perhaps for a glass of wine to disguise the pre-packaged essence of the execrable meals served aboard. When I arrive at a destination I would rather that my sensibilities be alive to the new experience.

This abstinence did not apply to everybody, obviously. It especially did not to a couple of young guys who were somewhat less constrained than the rest of us as they approached the stairs at the rear of the airliner where they unexpectedly and overwhelmingly were engaged by a blast of 32 degree Mexico air, which did not even remotely resemble the chill November winds of Canada.

I had preceded them and was on the tarmac when I heard a soft thud and a grunted exclamation. I turned and observed both of these young inebriates tumbling down the stairs, their hand luggage bouncing along beside flailing limbs and gyrating torsos.

Happily uninjured, they gathered up themselves and their belongings and, smiling stupidly, proceeded towards the main terminal where I was sure they would be encountering a red stop light at customs.

Those customs lights are a curiosity. After having answered a question or two from an official, the airline passenger stands somewhat bemused in front of a set of faux traffic signals, one red and one green. You’re at an ostensible, albeit transitional intersection: If the light flashes green, you’re “good to go,” (to recapture a current fatuous phrase designed further to emasculate the English language); if you get the red, you are directed to another official who, I suppose, could deny you entry into Mexico. In my experience, this official makes one or two cursory inquiries and then bids you farewell and a good stay. (Thankfully, there’s no disingenuous “have a nice day.” In Spanish, of course.)

Our first entry into Mexico by sea presented a perplexing geographic conundrum for us. After our voyage down the coast from Canada in our 42-foot steel sloop we sailed from San Diego and entered Ensenada, Baja Norte, our first official port of entry. There would be more entry ports to come; for, when arriving, the captain must bring his ship’s papers to the port captain for clearance, even if he had just been cleared elsewhere. It is another of those bureaucratic annoyances, but, hey, it keeps people employed.

The person in charge of the Capitanía del Puerto in Ensenada was not where you would expect to find him, near the port. His office was somewhere in the town: all I had to do was find it based upon dubious directions offered by another sailboater.

After wandering around in an increasingly hazy daze for an hour or so, my bulging ego succumbed to my suppressed logic and I actually asked somebody. For a man, it seems to take at least an hour to break down the natural reticence to acknowledge he is at a loss whether to come or wither to go. The Mexican whom I accosted did not have a clue where the port captain’s office was situated, but he gave me directions anyway, offering up a torrent of words orchestrated by a flurry of waves and a frenzy of finger pointing.

Eventually I blundered upon it by accident and proceeded to enter into the unenlightening intercourse associated with bureaucratic rigidity and superfluity. I had not seen such a fury of filling out of forms and of photocopying since the ’80s.

But getting lost and asking for directions in Ensenada laid good groundwork for the pending frustrations in the other ports of entry. All of the customs offices in these other so-called ports were situated in secret places known only to a select few and never to a visiting ship’s captain, and they invariably were remote from the waterways which provided the very justification for their existence. The capitán del Puerto in Mazatlan was particularly elusive, and when eventually unearthed presented a paper shuffle delightfully circuitous and mysterious. These theatrics were further obfuscated by the interruption of the siesta, which split the ritual in two and put paid to the rest of my afternoon. Regresa más tarde, por favor. See ya later.

Así es la vida.

There is a lot of discussion, sometimes in whispered undertones and at other times with outright alarm, about the dangers of certain border crossings because of the apparently raging wars among drug gangs and, more often these days, with the willing participation of the Mexican military.

My email box overflows with forwarded news stories from alarmed relatives and friends in the States and Canada. Drug czar slain, the headline warns. Drug cartels behead rivals. Mex military raids drug bar. 6 slain in Sonora shoot-out.

It’s enough to make you stay home with bed covers drawn over your head. I tell my friends that the only thing I have had stolen by Mexicans was my unwavering fealty to Canada: I have even considered living fulltime in Mexico, instead of just several months of the year.

I caution well-meaning doomsayers who are convinced that Mexico is a Hades-in-waiting to give it a try. But, I say, stay away from doubtful bars and bistros; don’t get drunk and insult your hosts, especially ones you’ve just met over a supercharged margarita, limit your drugs to those that have been prescribed and don’t flash the cash. High end resorts are places where you can get into a lot of trouble; they’re a magnet for con artists in Mexico just as they are anywhere else in the world where innocents attend and moronic tourists flock.

Notwithstanding all this chatter, we did once – and never will again – enter Mexico at a doubtful border crossing – El Paso to Cuidad Juarez. All the goodwill that Mexicans elsewhere in their country extend to visitors – save for Mexico City where we might just as well wear targets on our T-shirts – is expunged by the glowering rudeness of Juarez motorists. I suspect that many of these drivers are on edge, inhabiting as they do one of the most crime-ridden, murderous cities in Mexico, where bodies compete with cacti for pre-eminence in the adjacent desert. In the other Mexico most drivers, except for the ones who were ordained to run you down, defer to others with a courtesy not readily extended to fellow motorists elsewhere in the world. This is an assertion which will be contested, I am sure, but I have found most drivers here unfailingly courteous – at least in the smaller towns and cities. And those whose courtesy abandoned them were skilful in avoiding accidents which would have been inevitable back home.

We managed to get lost a half dozen times in Juarez – which recalled our first confused passage through the warrens of Tijuana while heading to La Paz . These days – in late 2008, the doomsday year of the meltdown – Tijuana has suffered a downturn as wary visitors bearing yankee dollars rebuff the uncertain blandishments of merchants and pimps alike. This probably has eased traffic quite a bit and made it less likely for one to end up aimlessly roaming back streets and alleys while trying to find the way back to sanity and safety.

I steel myself as we approach the border stations. Most of all, I take Vera’s advice and try to avoid saying something stupid, which is a sure-fire way of extending a half hour passage into a half day ordeal.

Be courteous and respectful, I tell myself. You’re a guest, so behave.

Keep it simple…

…and have a nice day.