Did You Know…?

I’ll break your jaw! (Chalco)

In the umbilicus (Xico)

Place of the squashed serpent (Coapatongo) [1]

Mexico’s place names or toponyms provide a rich and fun source for linguistic analysis. Indigenous peoples spoke languages that had no formal alphabet. They developed complex symbols (hieroglyphs) for place names that used combinations of up to three different kinds of elements: pictographs, ideographs and phonetic symbols. When the Spaniards arrived, they asked the locals what places were called, and then wrote the responses they received as best they could to match the sounds spoken by their unwilling Indian hosts. This introduced some inevitable distortions, partly because of variations in how the same place might be heard and written by different scribes.

Like anyone with poor hearing or a poor grasp of the local languages, the Spaniards tended to hear what they wanted to hear and write what they thought they had heard regardless of its actual meaning. For instance, while unlikely to be true, it is sometimes alleged that “Yucatán” actually derives from Maya Indians responding “I don’t know” when asked to name a nearby town.

Over time, many place names morphed in ways that make them barely recognizable today to any time traveler returning from the early colonial period. Numerous new place names were created and added to the gazetteer. Some existing toponyms were totally changed to reflect the importance of particular individuals, events or dates.

The place names with the most obvious meanings are those which are 100% Spanish in origin. A Spanish-English dictionary will quickly reveal the origins of the names of hundreds of places in Mexico. The following Spanish adjectives are commonly found in compound names:

- nuevo/nueva = new [Nuevo León]

- alto/alta = high or upper [Altavista = high view]

- bajo/baja = low or lower [Baja California]

- grande = large [Puerto Grande = large pass]

- chico/chica = small [Costa Chica]

The four cardinal directions also often form part of the place name:

- este = east [note, though, that oriente is used for east when describing a street, e.g. Hidalgo Oriente #123, not Hidalgo Este #123]

- oeste = west [poniente is used for streets]

- norte = north

- sur = south

As a geographer, I am naturally more interested in place names that reveal something of the geographic character of the place. The Spanish language has a plethora of words describing topographic features in the natural landscape. Spanish is similar to English in that landforms are named not only according to their shape or morphology, but also according to their relative location. In English, for instance, both a plain and a plateau are surfaces that are relatively flat; the former is lowland while the latter is upland. Spanish is even richer. In an article published in 1886, Hill describes how the published names on maps meaning “hill” or “hillock” include no fewer than 22 different words in Spanish, as opposed to only 16 words in English.

Common Spanish toponym elements related to relief and drainage include:

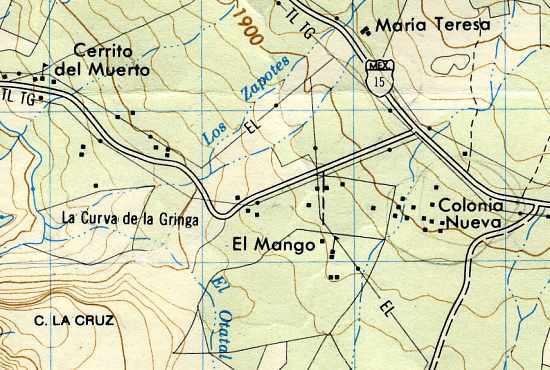

- cerro = hill

- sierra = elongated mountain range with sharp crest [cf cordillera = mountain range]

- peña = craggy hill [Peña de Bernal]

- loma = hill in middle of plain

- lomita = hillock (small hill)

- mesa = flat-topped (table) hill

- cumbre = summit or peak

- pico = sharp peak

- montaña = mountain

- valle = valley

- barranca = canyon

- gruta = cave

- cenote = limestone sinkhole

- agua = water

- arroyo = brook

- río = river

- lago = lake

- salto = waterfall

- cascada = waterfall

- ojo = spring

- caliente = hot [Aguascalientes = hot waters]

- presa = reservoir (and dam)

- ría = [cf río] ria (drowned river valley)

Coasts and coastal navigation were absolutely vital to the Spanish explorers and settlers, and so it is not surprising that they labeled coastal features with considerable attention to detail:

- mar = sea

- salinas = salt flats or salt works

- golfo = gulf [50+ km across]

- bahía = bay [smaller than gulf, generally less than 25 km across; bahías are largely absent on Mexico’s Gulf coast]

- ensenada = small bay or embayment

- puerto = port, and water approaches to a port [inland, puerto = pass or gateway]

- boca = mouth of a river

- playa = beach

- cabo = point or cape

- punta = point or headland

- isla = island

- ribera = bank or shore

As forests were cleared and inhabited settlements grew, more and more Spanish-language elements entered Mexico’s place name vocabulary:

- barrio = neighborhood

- colonia = quarter or district inside a town

- rancho = hamlet

- pueblo = village

- villa = town

- ciudad = city

- capilla = chapel

- puente = bridge

- balneario = bathing place or spa

- calle = street

- callejón = dead-end street

- hacienda = estate or large farm

- estado = state

- puente = bridge

Numerous other Spanish adjectives and words added richness to the diversity of names. Many place names incorporate elements depicting colors:

- blanco/a = white [Villa Blanca = white town]

- negro/a = black [Piedras Negras = black rocks]

- azul = blue [Agua Azul = blue water]

- verde = green [Cerro Verde = green hill]

Certain other terms marked locations thought to hold metallic riches and color-coded accordingly:

- plata = silver [Plateros = silversmiths]

- oro = gold [Santa María del Oro]

There are hundreds of other Spanish words used in place names, but here, we’ll limit ourselves to just three more:

- Heróica = Heroic [Heróica Zitacuaro]

- vista = view [Buenavista = good view, Vistahermosa = beautiful view, but note that some places thus named demonstrate a decided propensity for wishful thinking]

- escondido/escondida = hidden [Puerto Escondido = hidden port]

When creative juices dried up, early Spanish settler often resorted to copying names employed in Spain, even if they were not especially appropriate to the new location. For example, Guadalajara = dry stony river. The name is derived from the Arabic word “wadi”, and was used only because Guadalajara, Spain, happened to be the birthplace of Nuño Beltran de Guzmán, founder of Guadalajara, Mexico.

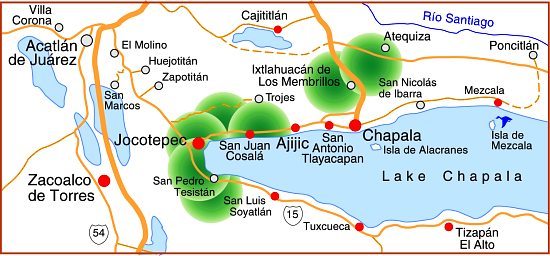

Numerous Mexican place names [Matamoros, Morelos, Hidalgo, Ocampo] emulate the names of famous individuals. A large percentage of place names incorporate saints’ names. San José is the most popular, followed by San Juan, Santa María, San Pedro, San Miguel and San Antonio. Saints’ names are often combined with additional elements such as famous people [San Miguel de Allende] or indigenous words [San Antonio Tlayacapan].

Still other place names commemorate an important date or event. Barra de Navidad [= Christmas Sandbar] on the Pacific coast was first explored on December 25, 1540. Elsewhere many settlements are named 20 de noviembre [November 20, Revolution Day] or 5 de mayo [May 5, the date of the Battle of Puebla].

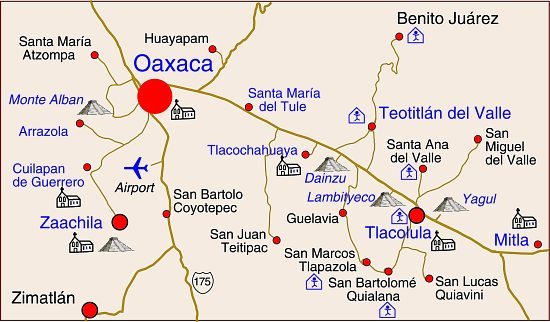

Among major cities whose names have a clear etymology are:

But even more fascinating, to me at least, than Mexico’s Spanish-derived place names are its indigenous toponyms. Perhaps the single commonest indigenous suffix used as a place name element is -tepec [Chapultepec = hill of chapulines (grasshoppers); Jocotepec = hill of guavas]. Other suffixes derived from Indian (mostly Nahuatl) words include:

- -apan = in/near water or river [Tequisquiapan]

- -atl = water

- -calco = in the house of [Nopalcalco = in the house of nopals (prickly pears]]

- -can = place [Coyoacan = place of coyotes]

- -cingo, -tzingo = (small) place of settlement [Chilpancingo = place of small wasps or small place of wasps, the Nahuatl word order allows either interpretation]

- -huacan, -oacan = place where they have [Michoacan = place where they have fish]

- -pan = in/on

- -ro = place [Copándaro – place of many avocadoes]

- -tepetl = mountain [Popocatepetl = smoking mountain]

- -titlan = near [Oztotitlan]

- -tla = abundance [Mapaxtla = abundance of mapaches]

- -tlan = in or near [Ocotlan = near the pines; Acatlan = near the cane]

My favorite place names are those that are entirely unexpected. One of the sharpest curves on the Mexico City to Cuernavaca highway is called La Curva de la Pera [= the curve of the pear]. While the derivation of this name may seem fairly self-evident, why would anyone call a 90-degree bend near Zitácuaro, Michoacán, La Curva de la Gringa? (see picture)

Inevitably there are also some anomalies. My favorites in this category include the railway stations of Honey in the state of Puebla (named for a famous railroad engineer) and Wadley in the state of San Luis Potosí. The latter is particularly strange since the letter w does not belong to the Spanish alphabet. I’ve never been able to identify the origin of the name Wadley with any degree of certainty, but for one possible explanation, see Mexico has many “Est”raordinary railway places.

[1] cited in Griffin, 1953.Sources:

- Driver, Stephen L. Spanish as a Language for Geographical Expression. CLAG (Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers) yearbook 1990, pp 3-14. [https://sites.maxwell.syr.edu/clag/yearbook1990/driever.htm]

- Griffin, Paul F. Geographical Elements in the Toponomy of Mexico. The Scientific Monthly, vol 76, #1 (January 1953), pp 20-23.

- Hill, R.T. 1896. Descriptive topographic terms of Spanish America. The National Geographic Magazine 7(9):291-302.

- MacAodha, B.S. Some major elements in Spanish placenames. Geography. 1979. Vol 64, pp 17-20.

- Macazaga Ordoño, César. Nombres geográficos de México. 1979. Mexico City: Editorial Innovación S.A.

- Manrique Castañeda, Leonardo (coord). Atlas Cultural de México: Lingüística. Mexico: SEP/INAH/Planeta. 1988.

Wow, this is super informative and a wonderful way into learning and remembering Spanish! Thanks so much for sharing your knowledge!

You are most welcome! Thanks for taking the time to comment. You might enjoy “Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico,” a book I co-wrote with Dr Richard Rhoda. Have a great summer!