The Months of Mexico

Roads in Mexico should display this warning: Use at your own risk.

Roads in Mexico should display this warning: Use at your own risk.

This country has one of the most extensive highway systems anywhere, providing convenient and indispensable connections among villages, towns and cities. In a nation where a minority of people owns automobiles, almost everybody depends on buses to get around. These vary between long distance luxury coaches offering air conditioning, clean washrooms and television, to hay-wired, rattle trap conveyances which shatter eardrums and spew purple-tinged fumes as they rumble at break-neck speed from town to town to disgorge long-suffering commuters travelling to and from market or work.

Those Mexicans who can afford to own a car — and there are increasing numbers of them in a nation where, along the back roads, it is common still to see donkeys and asses at harvest (much like the ones in Washington, London or Ottawa gleaning the treasuries).

Mexicans drive everything from expensive gas guzzlers to compact hybrids. Outside of the major centres it is commonplace to see pickup trucks in use, some of them in the high end class.

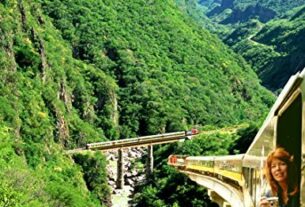

This spider web of byways ranges from mountain tracks linking tiny settlements to high speed multi-lane highways directly connecting the major cities and bypassing the innumerable villages and towns which dot the countryside.

Free roads or toll roads?

In most cases, these autopistas are twinned with libres — free roads — oftentimes running parallel to the expressways. These free roads usually were the original routes, pre-dating the modern freeways, and today are welcomed options for those who cannot or will not pay the tolls by which the construction of the fancy thoroughfares is financed.

In the cities several lanes of traffic funnel commuters in seeming chaos, and peripheral roads provide welcome bypasses to steer the long distance traveller away from the free-for-all city streets.

The autopistas are mainly trouble-free, but boring.

The free roads offer alluring prospects of change from the customary. They bustle with activity: lumbering farm trucks overburdened with sugar cane, melons, coconuts, sacks of oranges, cucumbers or limes, market pigs on their combined first and final voyage, leaving in their wake an air stream of nose-crinkling stench; superannuated pickups with a clinging cluster of human campesino cargo being delivered to another back-breaking harvest venue; speeding cars with white-eyed drivers hunched over their steering wheels intent on overtaking everything within range in their constantly-frustrated determination to gain some advantage in time. The motorist must be alert to unattended cattle wandering the centre line, sprawling dogs on the pavement edge and plate-sized tarantulas scuttling across the road.

Unlike on the autopistas, there is time for the free rider to take in the scenery: rolling terrain enlivened by semi-tropical forests clinging to the million green-clad mountains of Mexico, which always show an unannounced burst of red, yellow or blue where a tree or shrub comes into sudden bloom amidst the camouflage khaki of a winter hillside. These routes are sprinkled with monochromatic villages where usually a splashed-on swatch of ochre, yellow or red brightens a dusty dwelling. On the helter-skelter main roads in these villages and towns we pass by tiendas offering everything from toothpaste to tomatoes or a farmacia where you can purchase drugs that don’t require taking out a bank loan, although it might be useful to check their expiry dates. Next to a smoking, tantalizing chicken barbecue, beef taco cooks orchestrating the chuta-chuta dance of a meat cleaver on a chopping block mix their promises with the other cries of commerce. Amid the hubbub, modestly-attired women have arranged on rickety tables rainbow displays of vegetables and fruit, and offers of coconut milk and fresh-squeezed juice. In season, certainly in the tequila state of Jalisco, the incautious may select from a roadside array of gallons of the national drink, cheap to buy and guaranteed eventually to kill or maim.

Interesting as they are for the adventuresome, these free roads are filled with danger.

Overtaking and passing

There is a dominant strain of Mexican motorist whose actions are embodied in an impulse to take over the road: this is the over taker. Sometimes when he is over extended he gets to meet his Maker and, if he misses out on that he’ll surely greet the undertaker.

There appears to be a visceral force which galvanizes this rash gambler: upon seeing a car far off into the curve-blighted highway, the machismo gene must kick in and a huge invisible weight inexplicably is poured into his right foot, powering the car ahead at great speed. The objective is to overtake his quarry, and coincidentally to stay ahead of another driver who characteristically has taken an opportunistic position just behind his rear bumper and who has his own, not-dissimilar, mission: to overtake the over taker. As the over taker bears down on his quarry he is transmogrified into the tailgater. His thoughts have coalesced into an obsession: pass the gringo. This will be done, damn the curves or the solid white (Don’t pass!) lines.

On many occasions, I have been that dot in the distance, happily meandering among the potholes, when all of a sudden I am overwhelmed with a foreboding that I have been turned into a target. I have a reserved admiration for people who are driven to win, and in accordance with this sentiment I seek to accommodate all those who have such Type A personalities, which includes many Mexican male drivers and some of the females as well. Observing in my rearview mirror the missile bearing down on me, I consider: Do I accelerate to keep distance between me and my stalker? Or do I slow down and play dead? To avoid actually dying, I desperately seek options, but there are few or, usually, none. A turn-out or lay-by would be good; but not only is there no such safe haven, there isn’t even a shoulder to rely on.

On the road, the most intimidating of these drivers is the long distance bus driver who, I am sure, classifies himself somewhat of a pilot, lower in actual altitude but elevated in attitude. However once it gets its steam up, the bus veritably flies along, until it encounters me — a sensible, often fast, but not an obsessed motorist. If the terrain complies with an offer of a longish stretch without another set of competing over takers and tailgaters hurtling our way in the other direction, I ease out of this dilemma by slowing down sufficiently for the exchange to take place, first place for second. (I’m satisfied with silver.)

There is a protocol to be observed as well in the overtaking ritual, one that I first learned on the Baja California highway. This is the left turn signal courtesy: when the slow vehicle ahead of you — behind which you’ve languished for half an hour — flicks on his left turn signal, it usually doesn’t mean he is about to turn left (although that may be what he means). He is indicating to you that the road ahead is clear, as far as he can determine, an evaluation that should be placed in context: the road ahead’s clear in his mind, but maybe not so if you’re someone else behind the wheel. His idea of clear doesn’t necessarily mean that the road could not suddenly be rendered unclear, as when a couple of competing drivers come careering around a faraway curve towards you. In tennis, being caught in no man’s land means you’re likely going to lose a point. But in Mexico driving, it’s probable that you’re about to lose your life, unless you do something quick. The ditch is out of the question; in fact it’s out of sight, long gone in a cactus clad ravine. You’re glued to the waist of a semi trailer truck hauling two block-long containers, so it’s too late to drop back. You know very well that the two projectiles aimed at you aren’t even going to think about blinking. That presents the irretrievable option of accelerating like a Cape Canaveral launch, becoming for all purposes, another competitor in Mexican road roulette, and — at the last moment before eternity engulfs you — swerving in front of that nice guy in the truck who with a flick of his wrist hinted, Okay, it’s safe now.

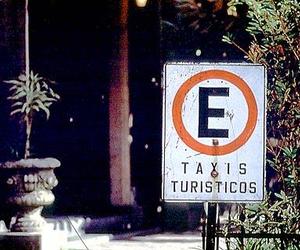

Mexico highway signage

Sometimes there are notices warning of inanimate dangers such as the invariably poorly-designed curves, sharp-edged shoulders that drop off into nothingness or shoulders that don’t exist at all, perilous intersections, and traffic lanes that turn from two into one or from one into none, snail-paced farm implements and, inevitably, roads under repair.

There never are signs warning of potholes, even though certain stretches of some roads, such as the busy Highway 200 between Puerto Vallarta and Bahia de Navidad in particular, always harbour potholes, most of which are obscured by murky shadows cast by forest canopies.

Although there are helpful notices cautioning motorists not to drive while tired or after (while?) drinking and to wear seatbelts and to not overtake on the shoulders (where they exist), they are a mere sprinkling compared to the rainstorm of other signs.

Highway signs are big business in Mexico. Many an uncle, cousin, brother or drinking companion of a local governor must have made his fortune in the manufacture or installation of these devices to provide motorists with information that, while often helpful and sometimes necessary, often is redundant or completely useless. Meant to guide and instruct, they often serve mainly to befuddle and amuse.

For example, an appeal to refrain from piling rocks on the road means nothing to the uninitiated who are driven to bemusedly flick through their dictionaries for a translation of the enigmatic admonition. How are they to know that it has been the historical practice of motorists who have broken down to set up a small mound of rocks in the road some distance behind their disabled vehicles as a signal to approaching motorists? Too frequently the pyramidal message was not dismantled upon resolution of the mechanical problem, and subsequent motorists would have to weave around the structure, until, I suppose, a luckless motorist passing in the dark would unwillingly rearrange it, perhaps with enough damage to his own vehicle to repeat the farce.

Probably the sign most prominent on Mexican roads is the advisement of a dangerous curve ahead. These signs sprout like expats at a free tequila tasting. There must not be any notice in Mexico as prolific as: curva peligrosa. This in part is occasioned by the innumerable curves in this nation of mountainous terrain, but a role in this burlesque is the sheer volume of these signs. Testimony to this is the number of them erected on the roads, up to a dozen or more for some curves. The first starts a hundred meters before the curve commences, followed by a cascade of warning signs that are often such a distraction that the curve is made even more dangerous.

Sometimes this torrent of admonition proves to have been a the-sky-is-falling torment: the curve is not at all as advertised; it is a fraud, a mere whimper of pending catastrophe.

In bewildering contrast another, definitely dangerous, deviation from the direct might be bereft of warnings, not even offering a suggestion that you’d better slow down or you’re toast.

I wonder who promotes this hysteria, who is the engineering genius who designates the number of signs, their strategic placement and determination of the degree of danger. I suspect that a highways crew gets a pick-up load of signs in the morning and is instructed to unload them by siesta hour, whatever it takes.

Another head scratcher is observed upon entering Oaxaca state, along the beaches. A sign would be observed and as you swoosh by, sending it wobbling on its base, you would catch out of the corner of your speeding eye an identical sign tucked in behind the first. A double take is in order, but by now you’re already too far down the road and too concerned about lurking speed bumps to do more than wonder. However, before long confirmation arrives: another double signage, a don’t-pile-rocks-on-the-road appeal, followed within inches by a sister exhortation. Somebody should send a letter to Mexico City asking the government not to authorize piles of identical signs alongside roads. There are scores of these dobles, repeating themselves all the way to and part way into Chiapas state. I suspect that some important person’s uncle made himself a tidy fortune doubling up on these; and, of course, an idiot nephew who was instructed to install them was equally enriched by taking the easy way. Oh, there’s one of them tarantula crossing signs. Let’s put another one right behind it. Just in case the first one gets eaten, I suppose.

© Bill Begalke, 2000

Over the years, I have driven the Baja a few times, Highway 200 on a number of occasions and numerous other roads big and small in the interior — from Nogales and the terrifying Cuidad Juarez in the north, to the Guatamala border in the south and right through to the Gulf of Mexico and back.

I’ve seen ’em all: smart signs, stupid signs, funny, puzzling; big signs, small signs, no signs. But the one that overtakes them all for histrionics and flat-out silliness is the one that jumped up and down, flapped its arms feverishly and cried out: Curva muy muy muy peligrosa — very, very, very dangerous curve ahead. It was dangerous all right, but no more so than hundreds of other hairpins I’ve negotiated in Mexico. And it had none of the aforementioned forerunners providing plenty of notice; it just stood there alone at the maw of its dangerous self, waiting for an accident to happen.

Topes — speed bumps on Mexican roads

The infamous Mexican tope is a murderous roadway device meant to slow vehicular traffic. But by its arbitrary design, it serves as well to infuriate and confound motorists, above all those of us who have not grown up among them.

There are two versions of Mexican speed bumps: the conventional and the reverse. The common tope crosses the width of a roadway from curb to curb or ditch to ditch. It can be of any height, depending I’m guessing, on the mood of the highways crew. Some are low-slung and wide, enabling the slowing car, truck, bus — or farm tractor — to glide over it with ease; others jut up like a surprise tsunami wave with great height but short width. These effectively slow speeding vehicles, but are likely to disable a vehicle under the control of an unwary or reckless driver, either by shattering the shock linkage or, even more efficiently, by crippling the steering mechanism.

© Bill Begalke, 2000

It is not uncommon to note great gouges in a tope where vehicles have bottomed-out on one of these stolid highwaymen, the driver not having correctly gauged its irregularities. Cleverly placed in the shadow of large trees, they are often difficult to see in time to slow down: which came first, the tree or the tope? Probably the tree.

Another devious method of disguise is the principle of neglect: whereas some are painted a bright colour, many others are simply left au naturel, ensuring that they blend in well with the pavement to deceive even the most alert motorist.

Traffic signs often warn of a lurking tope. In fact, building on the honoured tradition of multiple curva peligrosa signs as well as those self-reproducing dobles, some alerts are lavish in number and admonition: tope en 500 metros, says the first sign, tope en 300 meters, says the second, tope en 100 meters, tope en 50 meters. The apogee of this hysteria is attained with a sign right where the speed bump is located: it shouts tope! accompanied by an arrow belatedly directing the eye downward, at the axle-thumper presumably. Other times there is only a single warning, just the sign with the word tope and its buddy, the arrow, or simply an image of a car rising on a ramp. Other times, invariably in towns and villages, there’s just the abrupt tope, bone-jarring and terrible. They may be painted brightly, or not at all. There may be one in the approach to a town or half a dozen; they may be close together or far apart. They may make sense or nonsense. But they are real, and must be obeyed.

The other kind of tope is unofficial, but I have dubbed it the inverse, or reverse, tope. These crop up in neighbourhoods when, for instance, the citizens get fed up with the antics of a testosterone-laden teenager who announces his maleness by tearing up and down the streets, usually at 3 a.m. (Just like 16-year-olds back home.) The reverse tope is simply where a couple of volunteers dig a trench in the road, side to side, to curb the ardour of the nascent psychopath. Like its forerunner, the reverse tope is liable to be any depth or width; it depends on the whim of the spade wielders, or perhaps how deeply they had descended towards the bottom of a tequila bottle. Whatever the case, its intent is to ambush the unwary. (It does nothing to dampen the enthusiasm of the teenager: he just moves on to another tope-less, street.)

In the space generously allocated, I’ve been able only to touch the surface of this topic. All of this may seem negative and — as a result — unhelpful, but anybody who has survived the roads of Mexico has some inkling of the pitfalls (and pleasures) of driving in Mexico. Just like the Mexicans, the highways have their own personality.

Many people I have talked to in Mexico say “no way to the byways;” however to savor the true Mexico, you can’t do better than to get off the beaten track.

Just don’t drive at night.