Arts of Mexico

When Cortes and his small band of bounty hunters first set foot on the shores of pre-Hispanic America, little did they know what real treasures they would take back to the Old World. The precious metals and beautifully crafted artifacts were certainly without equal, but the real bounty was a gift that keeps on giving – food.

Today it is hard to imagine a world without the aromatic smell of a ripe pineapple or the texture of a juicy mango or rich, buttery avocado. And who can imagine a summer without some thirst quenching watermelon.

History tells us that Moctezuma’s table was truly a feast for a king. His meals were recorded to be varied and to have many courses. A typical menu could start with ceviche (a white fish marinated in lime with chili that is still eaten today) followed by roast turkey with sage, yams with honey, and baked squash. A fresh salad would be on the table along with a stack of warm tortillas, hand-made from maize ground on volcanic rock mortars. (These mortars are still available in the market place and used today.) His feasts always ended with a cup of hot chocolate possibly flavored with vanilla, a bit of tobacco and a hallucinogenic.

In fact, it seems Moctezuma drank cup after cup of hot chocolate all day long. The liquid was considered so special that it was served in golden goblets that were thrown away after each use.

From these early observations by Cortes and his men and the glyphs taken from various codices, it is evident that the pre-Hispanic people of Mexico loved their native foods, and that love affair continues to this day. Many paintings by Mexican artists reflect the profound connection the people have with their traditional food. In this respect, their work differs markedly from the paintings of the European schools.

Each image below is linked to an annotated enlargement.

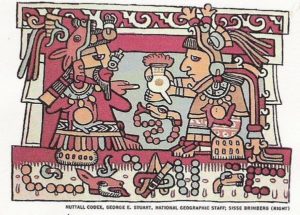

An early reference to food and the pleasure it brings can be found on a 12th century glyph from the Nuttall Codex. Here a Mixtec marriage is sealed with a mug of frothy hot chocolate. Mexicans still toast happiness with a cup of the now sweetened beverage.

Though Moctezuma ate a gourmet diet, he never touched pulque. This fermented, alcoholic drink was reserved for the elderly who earned the privilege after a lifetime of work. Pulque is still available at road stands and in pulquerias though it’s obvious that the age requirement is no longer an issue.

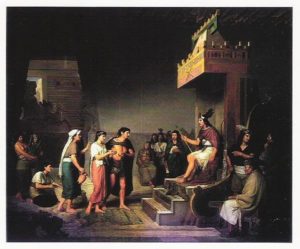

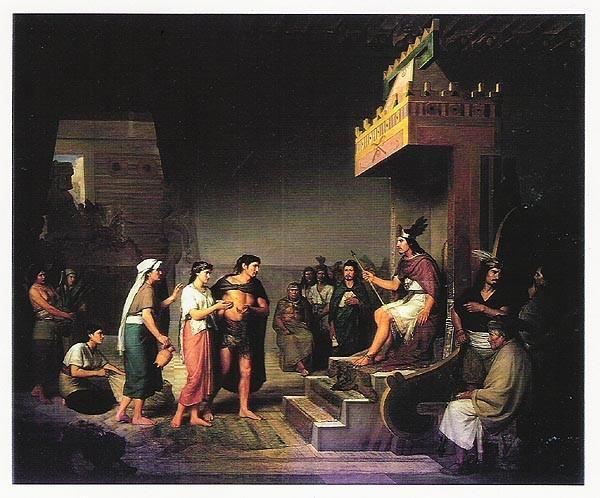

“The Discovery of Pulque” by Jose Obregon painted in 1869 is typical of the paintings of his time. The intent of his tribute to pulque was to rescue pre-Hispanic history from possible oblivion. It was a mission of many of the artists of his generation. In spite of their themes, many of the paintings from this period reflect European classical art and not the soon to emerge Mexican school. The King and his subjects as well as the architecture have a Greco-Roman aesthetic which has nothing to do with a pre-Hispanic reality.

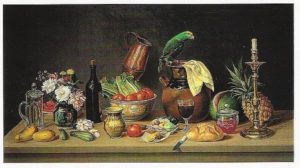

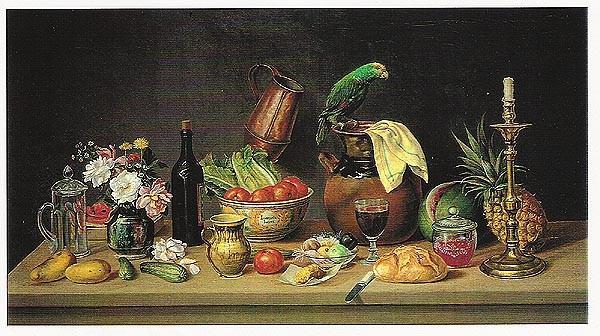

A really superb 19th century painter was Agustin Arrieta. His “Dining Room with Parrot, and Candlestick, Flowers, and Watermelons” is an excellent example of the provincial “bodegones” (still-life paintings) of his time. His work is easily identified as Mexican by its fruit and vegetables, pottery, and typical bread, still baked today and known as “bolillos”. All these items can be found in any “tianguis” (outdoor market) in Mexico. As for the parrot, it’s still a favored pet among Mexicans and émigrés residing in the country.

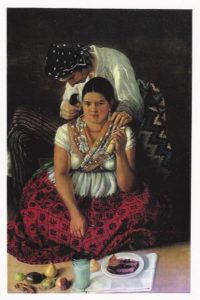

In “El Chinaco y la China”, Arrieta again makes food a prominent part of his work. Here we see a typical Mexican dish, enchiladas with a mole sauce. Along side the dish is a glass of pulque and some fruit, among them the cactus fruit known as pittaya, still sold on the streets of Mexico in season.

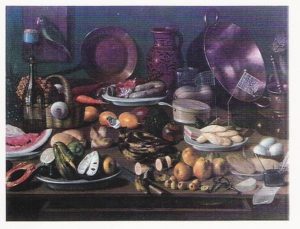

During the 19th century a large number of excellent still-life paintings were done by anonymous artists. In their canvases the foods and utensils of the Mexican kitchen were well represented. This work called “Still Life” is typical of the “bodegones” done at the time. It has the Spanish Baroque influence common during this period. The painting, which probably comes from Puebla, may have been the forerunner of the work of Agustin Arrieta, the previous painter mentioned, who became a master of the genre.

Fruit, sweets, cold meats, cheeses, and breads are scattered among copper, glass, and ceramic tableware, along with the ubiquitous parrot that Arrieta also uses. All of these products from the copperware to the small half round of white cheese to the square layered sweet on the dish with the cookies can be found in any Mexican market place today.

No inventory on painting and Mexican food would be complete without a bow to the great Hermenegildo Bustos. Bustos, a native of Guanajuato, was a self-taught painter with his own concept of painting. He called himself an amateur, but he was more than a mere amateur. In fact, his talent and sensibility make him one of the outstanding painters of nineteenth century Mexican art. His paintings are regarded as an expression of popular art, but they reached a level comparable to the level at the Academy.

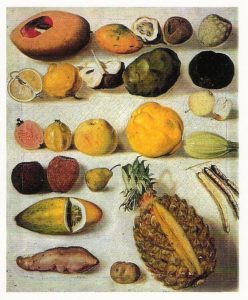

He did two still-life paintings which were never titled, one of which is this still life with pineapple. Fruit and vegetables fill the upper part of his painting while on the right is a pineapple placed on the diagonal. Much of the fruit and many of the vegetables are indigenous to Mexico and were not known to Europe before the coming of Cortes. Among them are the mamey, potato, yam, squash, pittaya, quince, zapote and pineapple. Mamey and zapote are still not well-known, which is a shame, as they’re both nutritious and delicious.

“The Farewell” painted by Felipe S. Guttierrez also dates from the 1800s. During this period, the growing mestizo population started to become interested in their indigenous origins. The attorney, Felipe Sanchez Solis, commissioned this painting, and the Indian taking leave is Sanchez Solis himself. The work is outstanding for the accurate, naturalistic representation of the humble interior of a peasant’s house.

In the family room we see two important foods in the Mexican diet – maize and squash – both native to the country. In the background a man holds a basket filled with fresh produce. He’s probably just returned from the “tianguis” with the vegetables for the big afternoon meal.

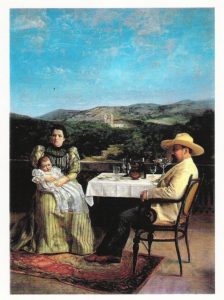

Antonio Becerra Diaz shows us another strata of society in his late nineteenth century work entitled “Los Hacendados de Bocas”. The table indicates that they have enjoyed a delicious meal. Grapes, watermelon, and other tasty fruit are presented in a silver pedestal bowl, probably European in origin, and the family is criollo (pure Spanish). Here, wine is drunk instead of pulque. Yet, a traditionally shaped copper pitcher sits on the table. This painting reflects the well-defined social structure of the era and mirrors the values of the Porfirio Diaz regime before the revolution.

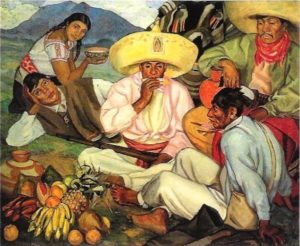

Fernando Leal’s painting, “Zapatistas at Rest” foreshadows the coming of the new Mexican School of Modern Art. The work was done in 1921 and shows Zapata eating with his men and the “soldaderas”, the women who followed and attended their needs. The group is situated between a bunch of fruit in the foreground and a majestic blue mountain in the background. Leal understood that food and landscape are powerful symbols that represent Mexico and its people.

His painting is French Post-Impressionist in style, but the subject matter and the emphasis is wholly Mexican. His revolutionary theme caused a hostile reaction among his fellow students at the Open- Air School where he taught and worked, but Vasconcelos saw the unfinished work and commissioned him to paint the first mural for the people. He was the first to paint a revolutionary theme from which so many others followed suit. In this pivotal painting in the history of Mexican art, food figures prominently.

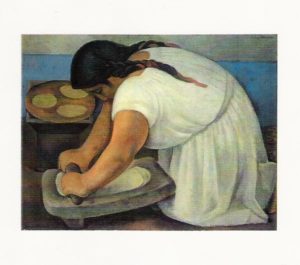

Painters still use food to depict the “Mexican ness” of their culture. Both Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros have depicted the eternal Mexican woman grinding corn – Rivera in “Woman Grinding Maize” and Siqueiros in “Woman with a Stone Mortar”. Rufino Tamayo often used indigenous fruit in his work as had Frida Kahlo and Maria Izquierdo,

Some of my favorite Mexican paintings where food figures prominently were done by Antonio M. Ruiz who painted “The Orator in 1939 and “The New Rich” in 1941. Ruiz was a post-revolutionary painter who understood well the profound connection Mexicans have to the life source that springs from their soil.