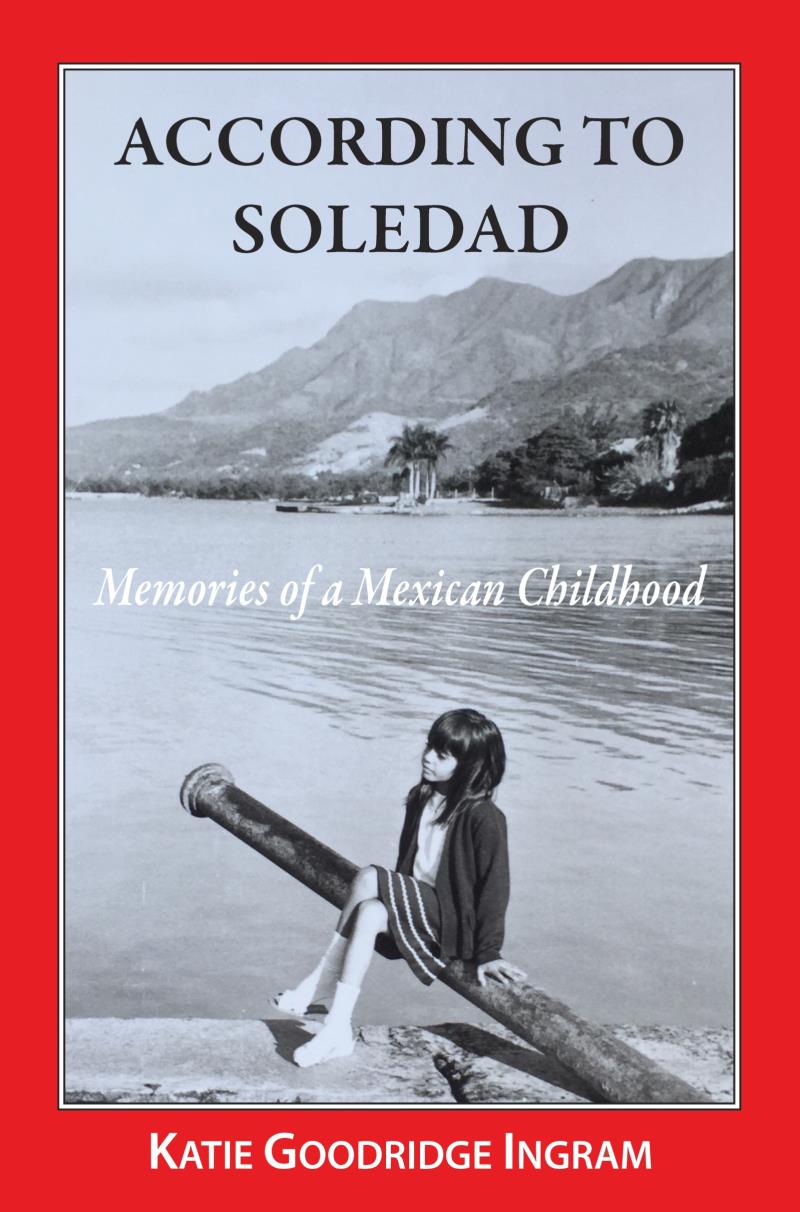

According to Soledad: memories of a Mexican childhood

Katie Goodridge Ingram. Sombrero Books, 2020.

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback

Katie Goodridge Ingram’s memoir According to Soledad is a rich and sometimes dark journey into her childhood years growing up in Mexico City and Ajijic, a small fishing village in the state of Jalisco. Her earliest years are spent in an affluent sector of Mexico City with her American parents who are constantly struggling to make ends meet. Very early she’s aware of being the product of two cultures, a perception she handles with true grit and acute perception. Her resilience is admirable. Her vulnerability is heartbreaking.

Ingram chooses the name Soledad for her heroine. She explains before one enters the first pages of the memoir that Soledad means solitude or grieving in Spanish. At first, I found it curious that she preferred not to use her given name even though this is her life story. But while pondering it, I realized from my own writing about my early years that a pseudonym helps to make distance giving a modicum of objectivity. At the same time the name gives us a hint about this child growing up in a culturally rich but emotional unstable home. Ingram is a poet with a masterful understanding of the power of the word, and this is certainly intentional foreshadowing.

According to Soledad gives us a riveting picture of what it was like to grow up in Ingram’s chaotic family. At the same time, it opens us to a full and immediate picture of Mexico during those years. Her use of language is superb. Her descriptions take you right there. There is great mystery and depth to Mexico, much of it illusive. One feels it more than extols it. With great poetic skill Ms Ingram surrounds the magic of what the culture exudes without pinning it down to pedestrian words that would stifle its liminal quality. This took great skill and an innate feel and love for the landscape and people.

In the memoir Soledad’s father deals in rare books. Soledad calls him a Book Man. He travels North and South America in search of old books for his clients. Unexpected finds are kept for himself until he finds the perfect buyer. His love for books is more than a passion. It’s an obsession though the family never comes to label it as such. He is gone a great deal of the time in his desire to unearth the rarest of books. His taste for women is less specialized, and he finds them wherever he goes.

Soledad adores her father, fights her brother Primo for his affection though the brother is obviously the father’s favorite. She waits for him to come home to tell his stories. He’s a story teller and dreams of writing them down one day. Soledad loves his stories. She does her father’s bidding, types his letters, tries to be letter perfect for him, and faithfully writes him when he’s gone. What he gives her is a love of words and an understanding of their inherent value. She grows up to use them in a way that would have made her father proud as is evidenced by her mastery in writing this memoir. If you love words, you will love this book—not wordy, just word perfect.

Her mother is beautiful and creative, and it’s from her mother that Soledad’s inherited her grit. The mother, a seemingly solid fixture in the father’s business, has set aside her calling as a dress designer to work tirelessly in her husband’s rare book business. She spends long hours touching up the colors on recently printed pre-Columbian manuscripts to enhance their value. At the same time, she manages to hold her own in a macho society where she often has to fend for herself, earns money when the family falls short, and still manages to be hostess to the cultural elite of Mexico City. She is jack of all trades and the glue that holds the family together.

For Soledad, her parents are both familiar and foreign. She feels her “whiteness” but her soul is tied to the culture she’s been born into. Pilar, her nurse, is the touchstone to her Mexican identity and in many respects is the family caretaker. She is the constant in an unstable family, and a solace to Soledad through many of her childhood mishaps. She is also a symbol of Mexico’s heart, the Mexico Soledad’s early years are nurtured on.

Whatever is lacking in financial solvency is made up in the family’s rich cultural life. Mexico City in those years thrives on its art and literature and is a Mecca for creative individuals from around the world. Soledad’s family is part of that cultural life. Fascinating people pass through their home, many of whom I’d heard about, some whom I’d known. It brought back a longing nostalgia for me though I’d met many of these people much later in life as I hadn’t grown up in Mexico and only arrived in the sixties.

Soledad’s mother has an affair, tragic and emotionally brutal in its aftermath—and brilliantly handled under the “pen” of Ingram. The family tries to heal, but the father cannot break his weakness for stray women, a pattern of behavior that started long before the mother’s affair. The family separates, and the mother leaves with her three children, the youngest still a baby.

And so life begins again in Ajijic, another place I know well, but again at a much later time. I wish I had been there in Ingram’s time. The physical description she gives of the mountains and lake are never changing, and takes me back to my years there. It reminds me why I loved living in the village. But the life she knew of fishermen mending their boats along the shore and the giant pools in the mango grove where women washed their clothes was long gone by the time I arrived.

Life in the village starts out hard. The mother, self-reliant and determined, makes it work. She eventually remarries, learns to weave her designs into cloth, and starts a thriving business. She creates beautiful clothing that even attracts the wife of the governor of Jalisco. Soledad and her two brothers grow and thrive, each in their own way. Her father dies a horrible, inexpressible death that makes the newspapers in Mexico City.

Some of Ingram’s stories are told in powerful and gritty language. Others are breathtakingly poetic. In her writing, you are present to every moment in the consummate way she uses language. I found myself in turn carried by the beauty of her language and the power of her intent. The country has a magic that she seamlessly captures, and a rawness that she never shies away from. In short, I was always where she wanted me to be.

She writes of an early infatuation with an older boy whom she’s just met secretly:

“I wanted to speak green. I wanted to say what floated away inside of me. I wanted to say the story books of damsels and princes. I wanted to say magic. I wanted to say words for all the colors that came through the sunset tules onto him all in white, words for the last light of the day and the beginning of gray, which took the words away.”

In another place she writes:

“We watched Lara throw up, and then, when she was standing in the mud crying, with blood on her legs, the baby fell out. I saw her pick it up. It was tiny and made the smallest baby noises I had ever heard. The doña ran out of a shed and cut the purple rope that hung from the baby. Everyone knew the girl had to do something, these things are secret. We watched the old woman slide the baby through the mesquite beams of the fence in front of the large black sow so no one would know, so no would find out or tell Lara’s mother. But we saw, and we could not close our eyes.”

According to Soledad is well-paced and beautifully written. Had I never lived in Mexico, I’d have enjoyed the read. Having lived there, it was a coming home to so many place I had known. At all times, the essence of the country is captured, and the child’s perception of her life there is viscerally and vividly portrayed. My only criticism is in not knowing the years in which the memoir takes place. The book is rich in historical perception of a time that has passed, and it would have added to the contextualizing of the story. But my observation does not take away from the beauty of her prose and the power of her story.

I highly recommend Ingram’s memoir. It is time well-spent if only for the sheer beauty of her use of language.