Located 60 km southeast of Mexico City about an hour and a half drive up a winding, but well-paved, highway from the international airport in the State of Puebla, Mexico is a town that more than time has forgotten. As someone who has spent the past twenty years in the travel business, I was surprised to be ignorant of the existence of the city of Puebla, considered one of the five most important colonial cities in Mexico. When my husband accepted the invitation to participate in the Congreso Internacional de Ingenieria Mecanica from the student chapter of the Society of Automotive Engineers at the University of The Americas there, the first step was to check on-line for background.

One link told me that Puebla was established by the Spanish in 1531 on the main route between Veracruz and Mexico City. I learned that its historic downtown, designed by a Spanish city planner, is still filled with elegant 17th and 18th century colonial art and architecture. Puebla was also the site of the pivotal battle in the Mexican Revolution.

When a photograph in the International Herald Tribune showed half a village tumbled down a slope in a mudslide in “Puebla, Mexico” we were more than a little concerned. The student who had extended the invitation e-mailed us back that everything was fine at the University — Puebla is the name of the province as well as the town; but he did say there had been “some damage” in the earthquake. We would learn that earthquakes and eruptions of the volcanoes that surround Puebla are routine.

On first sight, I was fascinated by our smoky companions Popocatepetl, the most impressive and visible from Mexico City whose name means “Smoking Mountain” in Aztec, and to the south, southwest and southeast, three more cones: one called the Sleeping Virgin due to its profile and the other, supposedly her lover who fumes because she sleeps. They are dark presences on the horizon as you enter the city proper.

Two of the University students picked us up at the airport, heralded by an e-mail that presaged some of the harsher realities of life in Mexico we would view from the road. Our contact forwarded us photographs to identify the students on sight. He apologized for seeming paranoid but said such precautions were prudent. Later as we rode the main route Via Volkswagen between the downtown and the campus the students told us that virtually anything can happen along the Federal highways. The clubs downtown must close by 2 am, but anything located on the verge of the state highways is unregulated, so the discos built there stay open until 8 am.

In nearly the same breath, the students relayed that Via Volkswagen has the highest highway mortality in the province. They also said the only time to worry is when the gendarme traveling behind you turns OFF his flashing blue lights.

That means you’re about to be boarded. This knowledge blended seamlessly with the sight of machine-gun toting police riding around in the backs of pickup trucks on the city streets. But such glimpses are part of the territory in this fascinating city; and probably the original inhabitants felt the same about the Conquistadores in the 16th century.

The road out of Mexico City leads higher and higher into clearer and clearer air mountain air that widens the views from the hillsides as you drive.

The countryside is reminiscent of Tuscany because of its tended fields and tile-roofed farmhouses. You’re more likely to encounter a solitary farmer sitting by the side of the road while his cows and goats graze along the highway, or a man behind a horse-drawn plow, than evidence of the fact that Puebla is the home of the largest Volkswagen Beetle plant in the world. On our drive, the low clouds concealed the cone of Popocatepetl, but the shocks of straw in the fields were shaped like miniature volcanoes to appease the gods?

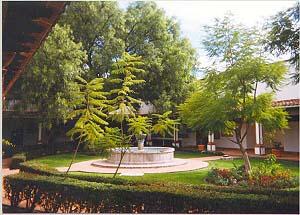

University of The America’s, Puebla

Our hosts had arranged accommodations on campus at the University’s Hotel San Andres, operated by the hospitality school’s students. The hotel is a low white-washed complex with tile roofs and a walled garden; the cheery reception area was filled with the warm welcome of the student behind the front desk and a collection of hand-crafted colorful furniture and decorations.

This was to become a pleasant and familiar home, as the accommodations included full breakfast (such as huevos rancheros and fresh fruit), presented buffet-style here each morning.

Our room with bath in the adjacent building was small but comfortable and just as color and handcraft-filled. The hotel is in the residential compound for the University, behind a gated wall with 24-hour security. The broad expanse of trimmed lawn and sculpture, stretching in front of the hotel, was often filled with children of professors and staff, kicking around a soccer ball.

At the end of the cul de sac where the hotel is situated we discovered a hidden treasure: a multi-acre garden showcasing roses, bird of paradise, hibiscus, geraniums, a succulent garden and shaded pathways paved in terracotta and glazed tiles. A collection of sculptural representations of Aztec symbolic figures completed the scene while neotropical birds sang in the shrubbery.

Another treasure was revealed the next morning: our first clear view of the volcano and the church of Cholula. The church is within a half-mile walking distance of the Hotel. All Spanish colonial arches and gilding, it sits atop a hill that is actually a Olmec/Teotihuacan pyramid. Popo rises behind it with snow on his peak and smoke lazily puffing from the caldera.

We did not spend much time in the traditional tourist sites in Puebla, the Cathedral or the colonial House of Dolls or other museums, because they were closed for repair due to earthquake damage. But we agreed that a stroll, like ours, through the streets of Puebla and a couple of evenings dining in the excellent restaurants would make a fine and inexpensive — weekend excursion out of the internationalism and air pollution inversions of Mexico City.

We were the only guests who seemed interested in getting to know the student engineers, so we were treated to incomparable hospitality in the best “Mi casa es su casa” (“my house is your house”) tradition. Squired around each evening at the end of the conference proceedings we were introduced to the city, which is actually several miles from the UDLAP campus, by the locals: the best roadmap to follow under most circumstances.

The first night of our stay two of the students picked us up in their old Toyota and escorted us to the Royalty Centro restaurant for dinner. The restaurant and hotel ( www.hotelr.com) are situated on the huge main town square, and offer a choice of dining outside beneath the heavy colonial arcade which surrounds the square (reminiscent of Bologna), or inside the formal dining room.

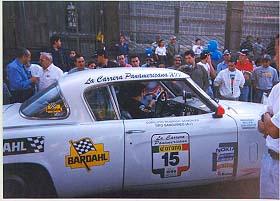

Carrera Panamericana classic car race

arrives in Puebla, home to the modern VW factory

We chose inside and started with glasses of wine and beer while encouraging the students to practice their English and tell us about their city. Salt-crusted steak is one local specialty; but I learned with delight that one of my favorite classic Mexican dishes — Mole Poblano — is so-named because of its origins in Puebla. The student who invited us to the Congreso turned out to be a ” mole poblano protector” of sorts, undoubtedly based on the superb and authentic version his mother and sister create.

Whenever he joined us for dinner he would advise whether this restaurant had “good mole” or not. The Royalty passed muster with a rich, dark, complicated, velvety sauce that the chicken had thoroughly absorbed. This first night our escort circled the square in his car to point out the City Hall and the Cathedral de los Angeles, which looks more like a fortress, made of huge grey blocks of stone piled solidly atop another.

We later learned that: 1) the Spanish had had a hard time getting the bronze bells into the belltower and supposedly miraculously overnight “the angels” had swung them in place (hence its name); and 2)that the earthquake had seriously damaged the dome and belltower so the sisters of the local parish convent were collecting spare change to pay for repairs while presumably praying for similar divine intervention.

The second night, six of the lads took us for dinner at “Azulejos” in the Camino Real Puebla. Azulejos are the vibrant tiles crafted locally and used on the facades of buildings, as beautiful as the perhaps more famous Deruta ceramics from Siena, but not as well known. It was an appropriate restaurant choice as each guest speaker at the Congreso received a dinner-plate-sized example of azulejos as a thank you gift.

The Camino Real hotel was built as a convent in 1594, and has retained the singular original architecture of the Spanish colonial empire as well as a large collection of original colonial art and craftsmanship. After parking the car in the adjacent garage we opened a massive carved stone door that led to an interior courtyard the size of a football field. Lit with amber lights, and opening to the midnight blue of the night sky, it felt like a reverse goldfish bowl that we were at the bottom of an aquarium of gold light in the middle of a blue ocean.

Surrounding the courtyard are the polished red tile corridors, hand-painted wood reredos and thick barrel vaults leading to the hotel registration, the formal second floor dining room, El Convento, and the bar. Diners in Ajulejos downstairs can also order from the dining room menu, while sampling the hotel’s selection of fine tequilas and wine. After a surprisingly-delicate “sopa rustica” containing fresh vegetables and sprouts in a light broth I enjoyed the duck with tamarind sauce, a subtle and sophisticated rendition.

The third night of our visit, we discovered La Sacristia after waiting an hour outside one of Puebla’s hot spots featuring a rowdy mariachi sing-along and traditional Mexican food. Aside from watching the Puebla equivalent of the Friday night club scene ebb and flow around the doorway we were also treated to a local happening: a van full of lurex-clad aliens on roller skates, handing out packs of grape lozenges under the watchful eye of their PR wrangler.

In contrast, La Sacristia was an oasis.

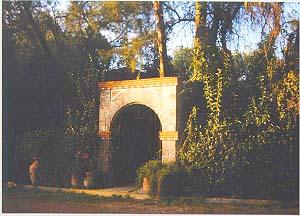

on-campus homes opposite the school’s

Hotel San Andres.

Nearly hidden on a side street and found only after many cell phone exchanges with the others who were meeting us there, this restaurant blossoms inward from the doorway, seeming to wind through a grotto filled with art, antiques (any of which can be purchased by patrons) and tiny white lights. Light jazz spills from the bar and fine tequilas, a companionable house red and baskets of fresh-made tortilla chips with both red and green salsas eased us into our dinner. As new arrivals continued to expand the table, the waiters managed to keep the glasses full, the orders straight and the food hot and correctly distributed. Of course, this was the place with the best Mole Poblano.

On the last day of the conference we heard that La Carrera Panamericana one of the great historic car races of the world would be passing through Puebla on Saturday afternoon. La Carrera is one of the most dashing, and most dangerous, road races still contested. It runs, every few years, the entire length of Mexico, 3200 km from the Guatemala border to the Rio Grande and is now restricted to the types of cars that ran the last unregulated race in 1950-54. Packards, Volkswagens, Studebakers, and vintage sports cars take part. Adrian Paul, star of The Highlander TV series, raced his Porsche in the 1997 event.

For once the road to excitement was leading into Puebla, and we were going to be there for the action! At about 2 o’clock on Saturday afternoon we followed the crowd to the town square and walked directly up to the finish line, marked by an archway of black and white balloons in a checkered flag design. Race officials in Tecate shirts were scurrying around in expectation of the first batch of cars who arrived about 20 minutes later, horns blaring and drivers waving.

We stood ten feet from the finish line, in the front row, watching the faces of Poblanos young and old, framed by the backdrop of the stones of the cathedral, the azure sky and the gold of the sunlight. Young boys in soccer shirts, weathered farmers in cowboy hats, affluent-looking young mothers in up to the minute fashion, and the ubiquitous collection of guys in polo shirts and jeans basked in the theater of the moment, appreciating living life in the fast lane even here in Puebla.

When we sat, much later, in a dark small square about four blocks behind the cathedral, listening to a dozen costumed mariachi players entertaining each other and watching how the students gently but definitively waved off the young children buzzing around them for coins, I was touched by that sense of surrealism caused when ancient paths cross modern ones. A visit to Puebla is a magical mystery tour.

Go.

WHEN YOU GO:

Puebla, Mexico is located in a broad, high valley about 60 miles southeast of Mexico City. Flights to Mexico City are plentiful. We flew Continental from Boston and via Houston for $458 each roundtrip.