Exploring Mexico’s Artists and Artisans

It is perhaps only in the “advanced” civilizations that artists are elevated above craftsmen, with the former thought to be leading the cultural vanguard while the latter are only practicing traditional folk crafts. This attitude often separates the artistic talent from the technical prowess of art. There is nothing wrong with a painter who relies on someone else to concoct the paints or a sculptor who depends on a foundry caster to transform a clay vision into bronze.

However, there is something fascinating about an artist who masters both the technical and artistic parts of his craft, who brings together the science and the esthetics.

Raúl Ybarra, who was born and raised in Sonora and now lives and works in San Miguel de Allende, is a silversmith with his own foundry and a jewelry designer with his own studio. In other words, he is an artist and a scientist, who works primarily with the lost-wax method, designing jewelry and small sculptures in wax, then transforming them into metal-silver, gold, copper, etc.-in his foundry.

He first designed jewelry as a hobby when he was studying biology in university. After earning his degree he worked for ten years in the US as an embryologist, the last four years as chief embryologist at the in vitro clinic at the Center for Human. Reproduction, a division of Baylor University in Dallas, Texas.

“During those years,” Raúl said, “I read everything I could find about jewelry making. When I learned that I would need a scale, I bought a scale. I continued this way till eventually I had all the equipment for a foundry.”

Then he returned to Mexico, uncrated the equipment, and taught himself how to run a foundry. His career as a jewelry maker had begun.

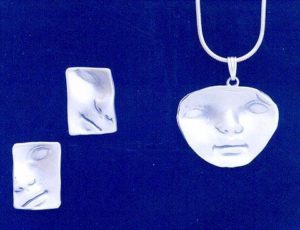

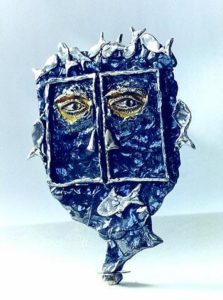

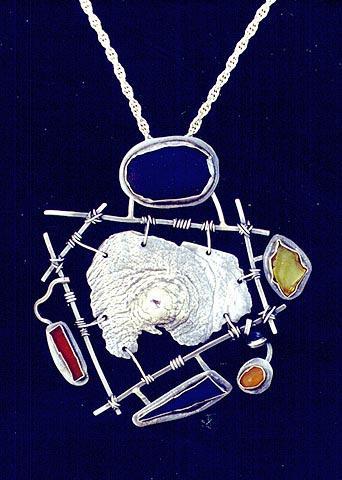

From the very start, his designs conjured up the word organic. His jewelry could be whimsical or witty, shamanic or seraphic. Petroglyphic designs from ancient Mexico would pop up, or printed verses of modern Spanish poetry. Parts of faces appeared, wings or a sundial sprouted from ancient torsos, or an oval stone set in silver became “Dinosaur Sperm,” the silver frame extending out to form a flagellate tail trimmed with stegosaurian ridges.

More recently whole processes from biology and embryology have insinuated their way into his designs. As the eye travels around one bracelet, its sees the wiggly sperm wooing the egg, then the growing zygote, and finally a tiny human face peering through the placental net.

One series of miniature sculptures is, somewhat formidably, called “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” which means the embryo in its development retraces the evolution of the species. Thus Raúl designs a silver crab, its claw lined with human teeth. And a human nose opens like a mollusk, which led to the speculation that maybe someday through recombinant DNA, perhaps we can train our congested sinuses to produce pearls instead of phlegm.

Raúl’s studio resembles an alchemist’s den. The equipment-the kiln, the centrifuge, etc.-are all pre-electronic. There are no digital screens or read-outs. There are notebooks everywhere because Raúl documents every step of every process, even noting the position of each item in the kiln, and uses this information to investigate any flaws and to refine his techniques. (His notebooks, a mixture of text and sketches, reminded me of the notebooks of Copernicus that I had once seen in library in St. Gallen, Switzerland.) He is also an inventor, recently redesigning the electrolysis equipment so he can electroplate clusters of jewelry instead of just one piece at a time. This disciplined approach to his craft harks as far back as college.

As an undergraduate he had no income to pay registration fees for classes, but he got permission to use the library and to take the exams. His tenacity was quickly reflected in his high marks on the first exams.

He was working toward a degree in biology in 1979 when the British produced the first test tube baby. He wanted to specialize in this branch of embryology, but no one in Mexico taught it. So, he began reading up on it at the library in all the American and European medical periodicals. None of his professors was interested, but one did give him access to a lab but offered no guidance or support. So, on his own, he began studying mice zygotes, concocting his own growth fluids, and growing them in vitro as he had read about. He even made microtools from glass to use under the microscope.

He began to publish his findings in Mexican medical journals. His reputation began to spread, and several younger students wanted to study with him. Since he was not a teacher, and no longer even an enrolled student, he struck a bargain with them. Four points he stressed with the ten students:

1) You will always be on time;

2) you will work as hard as I do;

3) when we are growing embryos, you will bring your sleeping bags because we photograph them every hour around the clock; and

4) since I have no money you will bring me something to eat – a sandwich from home or a snack from a vendor, but something decent to eat.

On the side, while sitting in his room, he made simple jewelry and sold it to other students.

For nine years he lived in a tiny rooftop cubicle (50 pesos a month), spent long hours in the lab, and published 23 articles in medical journals. Then, with what he thought was a good reputation, he went looking for work with a doctor. But Mexican doctors sent all their patients with fertility problems to the States. He could find none who wanted to branch into that field.

Finally as a last resort he ran a job-wanted ad in a US medical fertility magazine. He got several offers for interviews in different parts of the US, but he could barely feed himself. He didn’t have enough money to bus to the border, much less fly anywhere for an interview. Nor did he feel sufficiently fluent in English to attempt an interview by phone.

Then the Baylor fertility center in Dallas wanted to interview him and offered him a plane ticket and reservations in a hotel. He went. At the airport a limousine driver carrying a sign with Raúl’s name on it located him. So the moneyless young man hopped in next to the driver of a vehicle that was bigger than the room he lived in. After a few moments the driver said, “I think the doctors are expecting a much older man.” Then looking at Raúl’s rather well worn jeans, he said, “Do you have a suit in that bag? If you don’t, I urge you to rent one this evening, because tonight you are dining at the finest French restaurant in Dallas.”

He spent a week in Dallas being interviewed and shown around, then he came home. Not a word for six months, then Baylor called and offered him the job. He worked there for ten years. In the sixth year he became chief embryologist, and within a year under his direction, the clinic had the highest pregnancy rate of any clinic in Texas. By the time he left to return to Mexico, it was one of the top fertility clinics in the US.

Today the art of jewelry design, the technique of the foundry, and the science of embryology all reside comfortably and without division in the mind and imagination of Ra úl Ybarra.

Raúl’s jewelry has been featured in magazines and trade journals in Mexico, the US, and Germany. In 1996 several pieces of his jewelry were chosen to appear in the Latin/Hispanic Archive of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York City, a branch of the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, DC.

Raúl Ybarra had been invited to display his jewelry and sculptures at the 10th Expo-Fashion International. He set up three exhibit cases: two displaying his various jewelry lines and one displaying his one-of-a-kind jewelry and sculptures.

Expo-Fashion International, held at the Trade and Business Center of Mexico City on October 1999, is the largest and most prestigious fashion exposition in the country

PHOENIX RISING FROM THE ASHTRAY

(Author’s Sidebar)

Why would a 60-year-old man, who, thanks to Parkinson’s disease, has to wait till his pills kick in to tie his shoes every morning, shell out good money to take a class in jewelry making? We’re talking about a man whose only previous artistic efforts with malleable materials was at Lakeview Methodist Church camp in northeast Texas 50 year ago. When he was a 10-year-old camper, he attended a clay modeling class, where he rolled out a long worm of clay, curled it into an ashtray, and capped it with a v-shaped notch to hold a cigarette. He snuck home with it, wrapped it up, and presented it a month later to his dad on his birthday.

His dad unwrapped the objet d’art, looked at it with puzzlement, and finally said, “It looks like a dog dropping about to strike.” Actually, he used a terser expression than “dog dropping,” but either way, that is how my dad discouraged me-unintentionally I think-from dabbling in the plastic arts for nearly half a century.

One day in San Miguel de Allende I saw an exhibit featuring the mostly silver jewelry of Raúl Ybarra. His jewelry was eclectic, original, and intriguing. Also on exhibit were photos of his students and their works, and several of them were there wearing their own creations.

When I said, “I wish I could do that,” one of his students, the poet Ana Roy, said, “Do it! Raúl is a wonderful and encouraging teacher.”

Then I met Raúl himself and told him about my interest and my hesitation. He seemed so sure that I could manage the lost wax method that he invited me to visit a class at no cost and watch the process. After I watched other students for about ten minutes, Ra úl handed me a chunk of wax and showed me how to soften it with a hair dryer.

Over the next three hours Raúl showed me how to alter textures by impressing the surface with filigreed buttons and other objects and how to soften or even erase textures using fire. I discovered that the wax yielded to the pressures of my hand, but resisted the erratic movements of my Parkinson tremors.

Among Raúl’s most recognizable pieces of jewelry at that time were his angel pins and pendants. He showed us exactly how he made them by making one while we watched and then urged us to try one. To my surprise I came up with a raffish one I rather liked.

I also created a ring with a dog’s head, a cat pendant, a bug-eyed quadruped extraterrestrial, a fleur-de-lis, a barbaric bracelet, etc. I came up with 15 different pieces of wax jewelry. How many to cast into silver at a dollar a gram? I chose six. Incidentally, if a student wants to make a pendant for, say, $20, Raúl can weigh out the amount of wax that will cast into $20 worth of silver, and the cost is set, no matter how one shapes it.

My rebirth as an artist was complete when my friend Joan was visiting from Austin. I was showing her my jewelry creations, and she asked for the floral pendant and wore it on a chain framed in her décolletage for the remainder of her visit.