During Christmas holidays, a college sophomore stumbled into a board game, “Pancho Villa, Dead or Alive.”

He was surprised I had heard of Pancho but not the goofy game. He said everybody was playing it. I doubted that — but filed away his remark as another insensitive putdown, a way of saying I am old and out of touch. That will cost him when the will is read.

The way he explained, between snickers and chuckles, you get to drink a Corona, roll the dice and chase the wily Pancho up, down and around the Sierra Madres while trying not hurt your horses or stumble into some farmer’s marijuana patch.

See here, young man, I said, Pancho Villa is no laughing matter. He was a genuine Mexican hero — or a cold-blooded killer. Either way, he was no joke. After that, the sappy student got an earful, at least half of what I think I know about Pancho.

One hundred and fourteen years ago this summer, sharecropper Doroteo Arango, 16, became the talk of the town of San Juan de Río, in the state of Durango, in the colorful country that was to become the Mexico we mostly enjoy today.

Depending on which historian got it right, ranch owner Agustin Lopez Negrete made a tender, loving pass at Doroteo’s younger sister, persuaded her to elope, or raped her.

Depending on which author you choose to believe, Doroteo took up his trusty or rusty revolver and killed Lopez dead as a rock. Or, maybe he just shot him in the foot. News reporting was a little fuzzy in those days.

Either way, the chief constable, high sheriff, royal mounted police and highway patrol swooped in to arrest young Arango — a week or so after he had packed his lunch and headed for the hills.

Don’t fret if you don’t remember Doroteo but try not miss this part: This was the beginning of a spectacular revolutionary career. Or maybe it was just the first leap of an outlaw. Here’s hoping Mexican authorities didn’t suffer too much emotional trauma over their failure to apprehend the elusive youth. A few years later, General Black Jack Pershing and 10,000 U.S. soldiers endured similar embarrassment.

By now you know we’re talking about the man who became Pancho Villa, infamous Robin Hood bandit, quick on the trigger, a fierce patriot and two-bit hood. Pistols and pesos? Whiskey, women and song? Four out of five. He skipped strong drink.

Doroteo had to eat while hiding out in the mountains. He linked up with cattle rustlers led by Francisco “Pancho” Villa and got his fair share with each theft and sale. Alas, there are occasional misfortunes in life outside the law. Francisco was killed in a shootout.

No time for flowers. Doroteo seized the moment and assumed command. He took the fallen leader’s horse, gun and name. What happened after that is indeed the stuff of legends. Pancho and Associates stole and sold more cows, raided and plundered rich haciendas and even robbed a train. Every month he sent a stipend to his mother. He killed some big landowners so widows and orphans of his fallen followers could have little plots of their own. He provided a bag of stolen pesos so an old man could open a tailoring shop. A less fortunate man, who had fallen from favor, was allowed to dig his own grave.

No big deal, you say. Sometimes Pancho started with grandfathers and eliminated entire families. Could this be fact or is it fiction? Doesn’t really matter. Pancho Villa is one twisted tale from wild, wild times in Mexico.

Generations of Chihuahua peasant frustration erupted in 1910 and the revolution was born. Pancho was invited in. With crafty recruiting, he expanded his band of bandits into a fighting force of 28 killers on horseback. Tough team.

Pancho was first to beat back government soldiers. Poor people said “Wow!” His army grew to 500. His fame zoomed. By 1913, Villa had 3,000 troops, the infamous north division, often striking at night, fighting for freedom. Now and then he called timeout to steal a few more cows for food and funds.

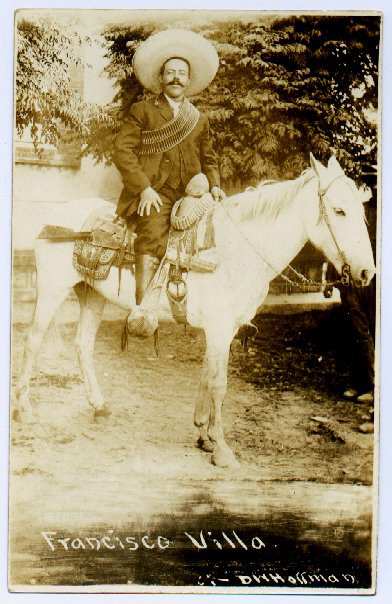

In a matter of weeks, Pancho Villa became a national name. Within months, he was an international celebrity, something of a folk hero in the United States. Newspapers sent reporters and photographers.

History has it that Pancho scheduled and fought 1914 battles with a U.S. camera crew in tow. You can bet your burro that Hollywood caught the fever. Actually, it was Mutual Film Company of New York. Contract called for $25,000 for exclusive rights to the revolution. Makeup artists supposedly powdered Villa’s face to lighten it for certain scenes. His hair was trimmed and combed. I am not making this up.

Along with boots and artillery, Mutual Film provided Confederate Army uniforms, boots and fancy guns for the front row — so Pancho’s scruffy soldiers would look better on the silver screen. The company filmed bloody battles at Ojinaga, Gomez Palacio and Torreon. The footage created one of the first U.S. newsreels.

I wouldn’t swear to this but Villa supposedly agreed not to fight at night. If there were technical problems, he offered to repeat an occasional shootout. We do know his army often traveled by train and that Pancho reserved space for reporters and set aside a special car as a film lab for Mutual.

Villa’s good relationship with the American media wasn’t an accident. He was a wild west show, cobblestone-street smart. He delayed an attack on Juarez to avoid conflicting with the World Series.

The Pancho Villa do-everything-right winning streak stretched into 1915, until Celaya, site of a stunning upset. He blamed the loss on the U.S. government helping the Mexican government. He got even by killing Americans wherever he could find them — including Columbus, New Mexico.

He had the audacity to send what was left of his army across the border to attack the United States of America. The Villa gang hit the military post in the wee hours of morning and shot up the town.

The story gets better. Knees jerked in Washington, D.C. The very next day, President Woodrow Wilson announced the dispatch of General Pershing and 5000 soldiers to capture Pancho. This was the Punitive Expedition. It was a bust.

Pershing had cars and trucks to run the dirt roads and six airplanes to scan the mountains. The idea sounded better than it was. Gasoline had to come in on pack mules. Two planes crashed the first week. The other four were soon lost.

The Punitive Expedition grew to a task force of 10,000 plus the famous “wanted” poster offering a reward of $5000 U.S. dollars when that was a holy fortune. All this worked in Villa’s favor. No way were visitors going to beat the home team. Many Mexicans undoubtedly misled many Americans, pointing one direction when they knew Pancho had gone the other.

In early 1917, Pershing gave up the chase with this memorable explanation: “Villa is everywhere and Villa is nowhere.”

It appears Pancho eased toward semi-retirement and by 1920 was a gentleman farmer in Canutillo. The fun didn’t last. He was ambushed.

Villa and his armed guards supposedly drove to the bank in Parral in his Dodge roadster on a sunny day in July. At an intersection, a man called out “Viva Villa,” the years-before battle cry for the old north division. Pancho smiled but the salute wasn’t a replay of fond memories. It was the signal to shoot. Rifle slugs peppered and penetrated the car. Villa was hit nine or 17 or 23 times, depending on your choice of historians.

In a surprising honor for a foreign invader, New Mexico created the Pancho Villa State Park in Columbus, 35 miles south of Deming on Highway 11. Several buildings remain from the time of Villa’s raid.

Pancho is a whole chapter in American-Mexican history? Sorry, but the answer is no. The college sophomore, on academic scholarship, admitted the board game was his introduction to this remarkable story. Before that, he had firmly believed Pancho Villa was a cartoon character from Saturday morning TV.

Some gringos live such sheltered lives.