A Voice from Oaxaca

Jacobo Ángeles’ work is prominently displayed in The Smithsonian, Chicago’s National Museum of Mexican Art, and elsewhere throughout the continent and further abroad, in museums, art colleges and galleries

One would be hard-pressed to search the Americas and find creators of folk art with more form, symbolism and importance to the development and sustenance of their culture, than those of Zapotec ancestry in the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca.

Many writers, including so-called experts in folk art, have mistakenly written that the origins of the tradition date back fifty or sixty years, to a small number of wood carvers residing in one of the central valleys of Oaxaca, a few miles from the state capital of the same name. The error has consistently been equating the recent commercialization of the art-form with its origins, and ignoring its pre-Hispanic roots and subsequent development.

Carver Jacobo Ángeless lives with his wife María and two children in San Martín Tilcajete, one of three main Zapotec villages where most of the residents earn a living from carving and/or painting colorful figures. Often generically referred to as alebrijes, they are shaped from the branches of the copal tree. The other villages are Arrazola and La Unión Tejalapan.

At the age of twelve, Jacobo began learning to carve from his father. Later on, he was mentored by elders in his own and other villages. “Over the past few decades our craft has without a doubt changed dramatically,” Jacobo explains, “with the use of more synthetic paints, a tremendous increase in the range of figures being carved, and with domestic and international demand for our carvings growing exponentially and affecting how and what we produce. But remember, my ancestors were carving animals right here in this region before the Spanish arrived in Mexico in the 1500s. And we were using only natural paint colors which we derived from fruits and vegetables, plants and tree bark, clay, and even insects. In my family, we still use what we find around us to make paints for our figures.”

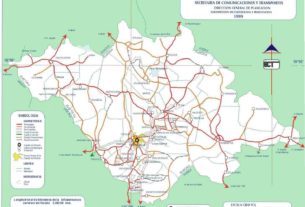

San Martín Tilcajete is about a 40 minute drive from the city of Oaxaca, along a highway leading to the state’s Pacific resort towns, including one of the oldest ports, Puerto Escondido. Puerto Escondido was a hub for the export of coffee and other cash crops during colonial times, but is now a popular beach destination for Mexican and international vacationers alike. Many travelers combine their sun and sand vacation with a visit to Oaxaca, searching out unique pieces of folk art including dance masks, pottery and painted clay figures, rugs and tapestries, and antiques from the colonial period forward. And of course there are the pre-Hispanic ruins, galleries, museums and renowned Oaxacan cuisine.

“My ancestors used a twenty-day calendar,” Jacobo continues, “and each day was represented by a different creature. So every Zapotec person had an animal with whom he had a connection, and each animal had certain characteristics that carried over to the individual as personality traits. For example, the jaguar represents power and ultimate strength, the frog is characterized by honesty and openness, the coyote watchful observation, the turtle always a troublemaker prone to breaking the rules, the eagle technical and strategic power, and so on. My people used to carve figures of just these twenty animals. They started out as small whittlings for good luck that people would keep in a revered place in the home, or wear around the neck as amulets. They also carved larger figures for their children to use as toys.”

Hunting Decoys

After much probing, an almost forgotten story emerges of the use of decoys of wood and other materials. Jacobo reveals, “My people used a variety of methods to attract different kinds of game, but for hunting eagles and other birds of prey, rabbits, and deer, yes they used decoys. A painted wooden snake would be placed on the ground in an area where ants had trampled the grasses so the snake decoy would easily be seen by eagles. My ancestors would attach a rabbit tail to one end of a straw hat, and at the other end another tail with a face painted on it. For deer, a crude wooden deer torso with real antlers would be placed in the tall brush. So carving was historically important to our people for not only totemic and related reasons, but it was directly related to our subsistence. All the written records from the period of the conquest, and not just local legend, confirm the importance of woodcarving.”

“But look at what we now carve,” Jacobo continues. “While in my family we still use natural paints, and still carve our twenty totems, we’ve transformed a simple yet important and symbolic tradition into something very different. In our villages, we now carve many more than those twenty animals because of collector demand. More importantly, we’re able to make our heritage better understood and appreciated by the world. In our own workshop, our painting depicts designs and representations of our culture – friezes from the ancient ruin at Mitla, symbols representing waves, mountains and fertility, the totems, and other metaphors for our culture today, and from the past.”

Indeed the world has taken notice – not only hobbyists, carvers from other countries, and folk art aficionados. Jacobo’s work is prominently displayed in The Smithsonian, Chicago’s National Museum of Mexican Art, and elsewhere throughout the continent and further abroad, in museums, art colleges and galleries. Throughout the year, Jacobo traverses the U.S. promoting Oaxacan folk art and his Zapotec heritage, teaching in a diversity of educational venues ranging from junior schools to university departments of fine art, and as honored speaker at art exhibition openings.

The Craft Process

A visit to the Ángeles workshop adjoining their home, accessed by a heavily pot-holed narrow dirt road towards one end of the village, affords an opportunity to learn about this extraordinary skill-set, from Jacobo, María – an excellent painter in her own right – and some two dozen other members of their family who produce some of the finest quality wood carvings found anywhere on the continent. The men do most of the carving, while women do most of the painting, but the tasks are definitely not exclusively based on gender lines. Carving is done with non-mechanical hand tools such as machetes, chisels and knives. The only time a more sophisticated tool is used is when a chain saw is employed to cut off a branch and level a base for the proposed figure.

Except when a special order is received, the woodworkers in the family are given artistic license to carve whatever figure they wish. A trozo of tree trunk will “speak” to one of these specialists, and that’s the inspiration for beginning to create a particular animal: the shape, thickness, and bends and twists in the piece come alive. A detailed outline is drawn on the bark, defining the image with greater clarity and detail. The sculpting in earnest then begins.

“From the female copal tree we are able to make figures out of one piece of wood, often very large and intricate. This wood is soft and easy to work with. The male tree is harder, and branches tend to be smaller and somewhat delicate, so we use it to make animals which we assemble in the process.”

The carving alone takes up to a month. The figure is then left to dry for up to ten months, depending on its overall size and thickness. Because of the properties of the copal, and Oaxaca’s semi-tropical climate, the wood is susceptible to powder post beetle infestation. Accordingly, during the drying process the piece is treated. It’s soaked in a gasoline/insecticide mixture for several hours. As an added assurance, it’s then placed in an oven, just in case eggs have evaded extermination. “All of our pieces are guaranteed to never have a termite problem,” Jacobo assures.

Since the figures are fashioned while the wood is green and more easily workable, the wood separates during the drying process. “There are a couple of members of my family whose main job is to fill the cracks before the painting begins.” They use shims, small pieces of wood that are otherwise waste from the carving process, to do part of the remedial work, as well as a sawdust-glue mixture. But even these slivers of wood and the sawdust have been cured. “We’re proud of our work, and never want to have any problems with any of our buyers, whether someone is spending $20 or $2,000.”

In the Ángeles workshop, in almost all cases, one person carves and another paints. Once a figure has left the hands of the carver, all proprietary rights are released, and another member of the family is entrusted with the painting. Nephew Magdaleno explains, “Occasionally one of my cousins will come up to me and say ‘what do you think about these colors or this kind of design concept for this coyote?’ and I’ll give my feedback, but it doesn’t happen very often, and in the end I’m almost always pleased with the result. For me it’s the form that’s most important, and for whoever’s painting, it’s the imagery it captures.”

One cannot help but gasp at the creative sculpting genius that goes into each piece: A starving dog scratching fleas, a bear with its paw in a honey pot, a snake constricting a wincing jaguar, a winged horse on its hinds, a woman with long braided locks and the body of an armadillo, or a deer, life-size by Mexican standards. There’s something particularly arresting about each creation: the ever-so-flowing and realistic movement, a fanciful stance, or a familiar pose striking a chord with our popular characterization. However the painting is anything but familiar. No color of the rainbow goes untested and the intricacy of and variation in design is remarkable.

Theories abound regarding the beginning of the modern-day manifestation of the art-form. Some say that because hallucinogenic mushrooms are native to this part of Mexico, drug induced revelations caused the imaginations of some to wander, ultimately becoming expressed in their carvings. The better explanation appears to be that knowledge of colorful, large, papier maché alebrijes or dragon-like forms that originated in the State of Mexico, eventually filtered down to Oaxaca, and were the inspiration for the fathers of contemporary painted wooden carvings. “You know, it’s not accurate to refer to what we create as alebrijes, because to the older generations of Mexicans, and to true folk art collectors, alebrijes were developed near Mexico City, and what we do is completely different.”

Natural Paints

Jacobo demonstrates how his ancestors created natural paints, historically used for dying clothing, painting buildings, and ceremonially as face and body decoration used for rites of passage, fiestas, prayer and other important occasions. Today their primary use, at least in these few villages, is for painting the wood carvings. He explains with the assistance of his machete and a tree trunk how he cuts away the reddish inside part of the bark of the male copal, allows it to dry, then toasts and grinds it. “This is a primary base that we use, which allows us to create a range of colors, tones and shades. Just watch.”

Using his hands as palettes, Jacobo begins by placing a small amount of the powdered bark in one hand, squeezes juice from a lime, creating a brown, which he then places on an unpainted wooden owl. “Yes the owl is also one of our sacred creatures, the great healer, quiet and humble.” He reveals, “Now over time, and in the sun, this color will change or fade and be absorbed into the wood. So what our ancestors learned to do was take the dried sap from the copal tree and heat it up with honey. The resulting liquid is then mixed with the paint, changing the color a little; see, it becomes a deep orange. But most importantly, it acts as a mordent, making the color permanent and a little shiny.” He adds powdered limestone, and the color changes to black. With the addition of baking soda and more lime juice, it becomes a deep yellow and, with more chemical, it miraculously becomes magenta. A new base is then started, with crushed pomegranate seeds. Magically the pulverized pink is transformed into green with the addition of limestone powder. Mixed with the magenta, it becomes navy blue. With the addition of zinc it becomes grey, and with more zinc, white. Blue from the añil tree, indigo, the next color, is altered with the addition of bicarbonate, zinc, lime juice or the powdered lime mineral. Corn fungus or huitlacoche, a black gooey culinary delicacy, when fermented and then powdered, yields ochre. The red of the dried and then crushed minute insect, the cochineal that feeds off the prickly pear cactus, becomes orange with the addition of the juice of any of a number of acidic fruits.

The demonstration terminates with Jacobo asking, “What´s your favorite animal?” following which, he finger-paints a rabbit from the rainbow of colors on his palms, as only Alice could have imagined.

Change in Oaxaca

With approximately 150 families now producing painted wooden figures in these and a couple of other smaller villages, the questions left unanswered remain: What facilitated and drove more carvers to adopt the papier maché style of using brilliant color combinations, and how can everyone in these villages make a living from this solitary art-form?

As with other crafts in the central valleys of Oaxaca, their production wasn’t always the primary means of sustenance for the populace. Traditionally, making crafts was a hobby or part-time trade, beginning with a paucity of items being sold to the odd passerby, adventurer or traveler. In the case of rugs or tapetes from nearby Teotitlán del Valle, there were trade routes that producers followed in order to effect more sales in other regions of the state, and in some cases beyond. But the primary means of family survival was working the land and small-scale ranching. In the case of the carving villages, there never was a broader market, although in San Martín Tilcajete embroidered shirts, blouses and dresses were an extremely well-received craft product throughout the 1960s and into the ’80s.

Dramatic change in production and marketing of wooden carvings had its genesis in the 1940s. The Pan-American highway cut through the Sierra Madre del Sur mountains, reaching Oaxaca, opening up the state to the north, in particular Mexico City and the border states. Until then, Oaxaca was relatively isolated notwithstanding a rail connection. By the 1950s and early ’60s, Americans and Canadians were prospering from the post-war boom, credit cards had been mailed to virtually everyone, and word spread of a new kind of vacation, in a third world country called Mexico. Jet air travel facilitated the transformation. The women’s movement meant more two income families, resulting in more disposable income for traveling. Mexicana Airlines and Oaxacan travel agents partnered to begin offering tour packages, which further facilitated tourism to the region.

The hippie movement of the 1960s and early ’70s brought Oaxaca to the forefront of the alternative lifestyle, with throngs of youth and their pop idols traveling to Huautla de Jiménez, then a tiny Oaxacan village, to eat hallucinogenic mushrooms with the now infamous healer María Sabina. North American youth saw and purchased the first generation of contemporary wood carvings.

By the 1980s, as a consequence of multiple factors, Oaxacan alebrijes had become well-established as folk art, with the market continuing to grow. The economic implication was that farmers and ranchers were able to spend more time carving and painting, and less time in the countryside and in marketplaces vending their produce and animals. With a new toll-road opening from Mexico City to Oaxaca in 1995, access to the southern state became even quicker and easier, and safe. In good conscience, travel writers were no longer able to warn tourists about driving the switchbacks, back-road banditos or cars overheating on secondary roads without service stations.

The Future

The future market for the art form? While the odd visitor to a Oaxacan coastal resort such as Puerto Escondido, or the more popular Huatulco, does visit the state capital and the workshops of carvers like Jacobo, most do not. Within the next four years, a new highway to the coast will open, cutting road travel time by a third or more. Even more sun worshipers will visit Oaxaca, and marvel at the art of Jacobo and María Ángeless.

Since opening their family workshop in 1996, without a doubt Jacobo and María have singularly raised the quality bar for other villagers who aspire to mirror their success. With Oaxacan wood carvings of superior quality now well established on the world stage, and access no longer an impediment, the challenge for others in San Martín Tilcajete will be to achieve the success of the Ángeles family through production of like quality, until now eluding most.

A challenge for all carvers in the region is to ensure a continuous supply of copal to meet demand. A reforestation project begun about fifteen years ago by the late master of contemporary Mexican art, Rodolfo Morales, continues through his Foundation. The Ángeles family and their friends and other villagers spend the last Sunday of each July, in the midst of the rainy season, planting. This is a part of the sustainable living concept for them – ensuring an ongoing supply of raw product, cutting only branches for making figures so that the tree continues to grow, reducing waste by utilizing the slivers and sawdust in repair work and any remaining twigs and branches as firewood for cooking, and using the sap and bark in paint production. “And you know,” Jacobo reminds, “we’ve also been using the hardened sap from the tree as incense, mainly at religious ceremonies, for generations. There are even knife-makers down the road in Ocotlán who engrave their hand-forged blades using a special ink made with the sap. Have you visited the cuchillería of Ángel Aguilar?”

For high end collectors, we can only encourage the success of all efforts and projects aimed at maintaining the growth and development of the Oaxacan woodcarving tradition, since it satisfies and advances our penchant for and obsession with quality hand-fashioned craftsmanship. For the artisans in the region, aside from the obvious economic importance, it’s part of maintaining their Zapotec heritage and illustrating the richness of the culture to the broader world.

Contact Information

The workshop of Jacobo and María Ángeles is located at

Calle Olvido #9, San Martín Tilcajete, Ocotlán, Oaxaca

Telephone: (951) 524-9047 website e-mail – [email protected]