One of the perks of living at Lakeside is the ubiquitous exposure to the religious art of the Huichol people. The artwork, so vibrant in color and rich in symbolism, effortlessly draws the viewer into its compelling world of magic and myth. Chapala Lake, with its small villages sprawled along the banks, is considered a sacred region to the Huichol Indians. As a result, those who live in the area are fortunate to be witness to this unique and highly creative culture.

The homeland of the Huichols is remote. It is protected from the outside by the difficult access to its communities in remote parts of the Sierra Madre Mountains in the states of Jalisco and Nayarit. Due to the isolation of its villages, the people have until recently managed to resist all but the most minor modifications from western sources. As a result, their art – synonymous with religious devotion – has remained in tact and intensely personal.

The word, Huichol, derived from Wirrarika, is the original name of these indigenous people. It means soothsayer or medicine man. The medicine man is the shaman who links the community with the “other world” from where their creativity pours forth as a gift from their deified ancestors to be given back as offerings to the gods.

Because the Huichol believe God has given them everything including their talents and abilities, pilgrimages are made every year by families as well as single individuals, young and old, to the sacred land of Wirikuta to hunt the Blue Deer (peyote). They bring with them offerings in return for the gift of making art and entering the priesthood. The ceremonial offerings include pictures, masks and candles and are considered material forms of prayer.

The Huichol believe their deified ancient ancestors, the First People, once dwelled in Wirikuta and were driven out into the Sierra Madre Occidental to now live a mortal agrarian existence. The Wirikuta desert is located to the northeast of the present Huichol communities. The pilgrims, led by a mara’akame (shaman) to cleanse the way, travel 600 miles round trip to re-enter the sacred land.

During the trip, they perform a series of rituals and ceremonies to transform themselves into deities. At different locations, they adopt more and more of their divine identities and assume the feelings and attitudes attributed to the First People.

If the ceremonial thoughts and actions are properly performed, the peyote will be found and “slain” with a bow and arrow. A slice of peyote will be given to each of the “peyoteros” who will then have their own personal visions. They will talk to God, receive instructions about how to proceed and will, thereafter, sing, cure, or create.

This moment of the sharing of the peyote is the fulfillment of the highest goals in Huichol religious life. They have traveled to paradise, transformed themselves into deities, communed with the gods with whom they don’t stay long, and then return as mortals.

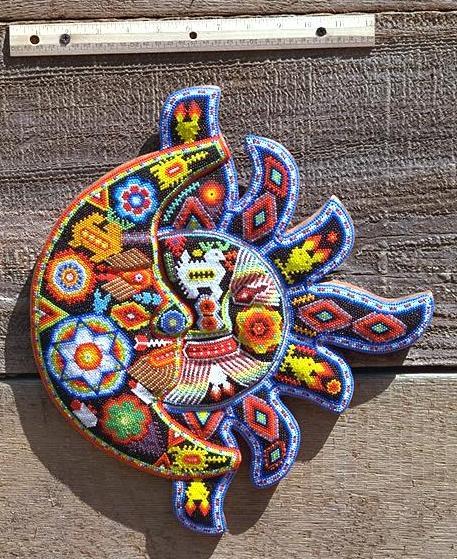

From the ecstasy of that experience the artwork of the people is born. In the Huichol culture, there can be no art without religion or religion without art. Religion is not a part of life. It is life. The gods are everywhere including the trees, hills and lakes. Even the lowly stone has a soul. These intensely religious people immerse themselves throughout their lives in this awareness through ritual and the execution of sacred symbols.

Art is the people’s means of direct communication with the deities. It is meant to ensure prosperity, health and fertility, and bountiful crops. Its application promotes the general welfare of the community and is always functional as well as beautiful.

“Jicuri”, the peyote plant is prominent in Huichol art. It is the plant of life that promotes harmonious relations with the gods. Sometime it’s represented as the original ear of corn because both carry the colors of white, yellowish green, red and blue. Sometimes it’s represented as antlers, which is a symbol of the first jicuri. All three representations hold the same meaning in Huichol myth and are interchangeable in symbolic meaning.

Another prominent symbol in Huichol art is the serpent. Because it protects corn and peyote, it is one of the most powerful animals in the Huichol cosmogony. Four female deities are represented by the serpent: Rapabiyema, the blue serpent, who lives in the south. Kapuri, the white serpent, who lives in the north. Sakaymura, the black serpent, who lives in the west. And Vaaliwa’me, the earth mother and red serpent, who lives in the east.

Takutzi Nakahue, mother of all gods and of corn, with her symbols of the sacred tree, the armadillo, the bear, the water serpent and rain is also well represented. As is Tamat’s Kauyumari, the older brother who shaped the world. He can appear in the guises of deer, coyote, pine tree, or whirlwind.

Tatewari is the spirit of fire, who lives on earth and is the god of life and health. He is often represented by a reddish-brown color. Tatewari is the chief ally of shamans and accompanies the pilgrims on their journey to Wirikuta.

All of these symbols and many more are produced in the highly decorative art form of which the Huichol are masters. Every item, from carved musical instruments to masks and votive gourds, carries heavily symbolic, esoteric, and beautifully rendered symbols.

Even clothing is a sacred manifestation of God’s work and worthy of prayer in the form of artwork. Huichol men have embroidered symbols and patterns cross-stitched into their clothing. The hems of their trousers often bears the flower pattern of the peyote plant. Boys’ hats are decorated with squirrel tails and the feathers of eagles and hawks, symbols of the first peyote hunt. A Huichol in traditional dress on the streets of a dusty Mexican village is a beautiful sight to behold.

The Huichol use beads, yarn, and wood in their highly creative and imaginative work. In the market places of the small Lake Chapala villages, one can find a Huichol alone or a family working on beautifully beaded necklaces or earings. They are using the same tiny beads they use to decorate their masks, votive bowls known as rukuri, and animal figures.

Yarn painting, a relatively recent innovation, is very popular with tourists. As with a lot of the beadwork, the surface of a plywood board is first coated in beeswax that is softened in the sun. Strands of colorful yarn in contrasting colors are then pressed into the sun-warmed wax.

Although the work is still based on interpretations of traditional religious stories, yarn painting has become very much an urban enterprise, and a number of Huichol now derive their livelihood from their art. As a result, many have left their homeland in the rugged and isolated Sierre Madre Occidental mountains to live in small towns and cities where there is an outlet for their creations.

Yarn painting is not sacred as it has no place in traditional Huichol culture. However, the subject matter of the paintings represents religious themes such as ceremonies, fiestas, and the gods, and often tells of events from Huichol mythology. In keeping with Huichol tradition, the paintings are not titled but often tell the story on the back.

The Huichol will say that when they do their work for God they think of God, and when they do the work for commerce, they do not, but the skill, technique and vision are the same. And it’s through God that they have been given their gift.

The only sacred yarn paintings are the ” nierika” or God’s face, which symbolize the threshold or passageway to the supernatural realm. They are small, disc-shaped, devotional objects often deposited in sacred locations as an offering.

The other sacred use of yarn is in the “tsikuri” or eye of God. It’s a wooden cross with strands of yarn wound about it in a diamond pattern and is a symbol of power to perceive and understand the unknowable. It serves as a type of votive offering to the guardian god of a child. Each year the father adds a section to the object, which is left in sacred places. It’s a beautiful object and can be found in the market place.

Art for the Huichol people was always a means of encoding and channeling sacred knowledge, insuring the continuity and survival of the legacy left to them by their pre-Columbian ancestors. It was seen as prayer and provided direct communication with and participation in the sacred realm.

However, by the middle of the twentieth century, modern life started to make in roads into the Huichol community. It became evident to the people that they would have to eventually switch from an agrarian economy to a money-based economy. At the same time, their sacred work drew the attention of outsiders. As a result, they began producing items for expressly commercial purposes.

Hundreds of families started to support themselves through making and selling their own artwork consciously adopting new materials and incorporating new objects into their work, though always preserving their original symbols.

Today, they see their work unsold and undervalued. They feel they are giving so much of their culture with so little compensation that there has been talk in community meetings that if their artistic works are not valued, they will stop producing them commercially. This may heal a rift that has been growing in the community for years, as there are many who aren’t happy to see their sacred world commercialized.

Still, I’m sad to say, it may just be a matter of time before the Huichol are integrated into the western world. The government has built airstrips into these remote communities and the outside now has easier access into these remote regions. For whatever will be gained, so much may be eventually lost.