Mexico Design & Style

Mexican cocinas (kitchens) beckon with their colors, simmering aromas, humming activity and cherished implements that exude time-honored traditions.

One of the most captivating and busy rooms in the Mexican home, the cocina is rich with traditional design elements–a bright array of ceramic tile, handcrafted furniture, and local crafts. Each Mexican kitchen, especially those in old colonial homes and haciendas, had its own secrets, recipes, and delights.

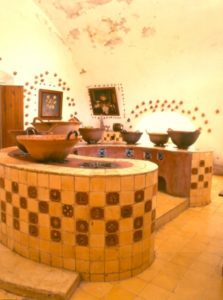

Because hacienda kitchens often had to prepare meals for hundreds of people, they were spacious, well equipped, and always busy with activity. They centered around the tiled brasero, or hearth, where charcoal-burning stoves were set into long or horseshoe-shaped counters. In addition to the countertops, tile was used throughout-on floors, walls, and sometimes even the ceilings. Early hacienda kitchens were influenced by the cavernous kitchens of Mexico’s colonial convents. In Puebla, the vaulted ceiling kitchen of the Convento de Santa Rosa is a masterful example of a space smothered in small glazed tiles. Here, the famed mole poblano made its first appearance in Mexican cuisine.

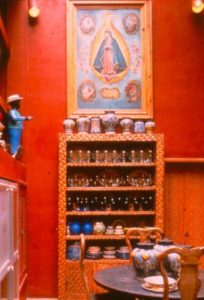

Against a backdrop of lustrous tile, early Mexican kitchens were simply furnished with a variety of country elements that possess timeless character and ingenuity. Familiar elements included hearty wooden prep tables, stools, and chairs, to a variety of hand-carved stone and wooden vessels including mortars, sugar molds and cheese presses. Always present was the ubiquitous trastero, or open cupboard, designed to hold plates and cups within easy reach. Piles of parsley, cilantro and chiles would fill handwoven baskets, while large, hollowed gourds kept freshly made tortillas warm. Stacks of large clay ollas, or cooking pots, were often stacked upside down, awaiting daily use for rice, beans and moles.

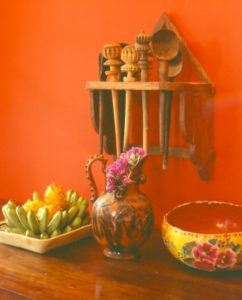

Iron wall racks would hold a sea of spoons, ladles, and chocolate whisks. Simple, wooden spice racks, called repisas (hanging shelves) were often decorated with scalloped edges or decorative crests, and lined with jars of peppercorns, cloves and cinnamon sticks.

Colorfully painted repisas continue to be popular accents in today’s working kitchens. Candles or matches are easily accessed in the small drawers of many repisas, while the shelves play host to spice jars, small glasses and carved gourd bowls and cups (jicaras). The ornate style of repisas from Oaxaca and Puebla feature bright colors and floral motifs, while those from Chihuahua and northern Mexico are typically crafted from natural pine and mesquite.

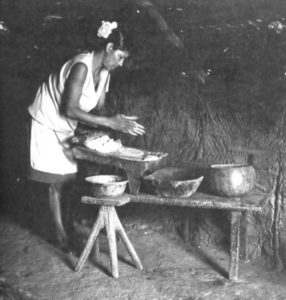

As homegrown chiles and spices are essential to the Mexican diet, the following elements are common sights in Mexican cocinas: pre-Hispanic molcajetes (three-legged stone mortars used especially for grinding spices), metates (used to grind corn and chocolate), bateas, (dough bowls), wooden tortilla presses, earthenware comales for cooking tortillas, and copper cauldrons for boiling stews. Side by side, these elements play a vital role in the daily ritual of tortilla-making and sauce preparation.

Found in a variety of shapes, the most common batea is rectangular with rounded edges and has a depth of approximately three to six inches. Larger sizes can be found in restaurants and panaderias, (bakeries), where greater quantities of ingredients are used; and even larger, more robust bateas were carved from thicker pieces of wood and used for such hearty tasks as washing clothes or soaking craft materials such as amate, or bark paper.

Our special affinity for culinary antiques such as wooden tortilla presses, ladles, and grain measure boxes-the unusual and utilitarian-has often led to searches in remote locations high in the mountains of southern Mexico. While doing research for our design books The New Hacienda and Mexican Details, we encountered one such adventure: an hour-long burro ride was endured to reach a dormant coffee plantation where large coffee morteros and manos, (large pounding sticks) carved from durable hardwoods, were discovered. Though coffee hadn’t been crushed in the mortars for several years, the aroma of the beans was still pungent. Even after the three-foot tall vessels were shipped back to the United States, they were redolent of Oaxaca café.

Country vessels and objects often date back several centuries-indeed, the molcajete is well documented as stemming from the pre-Columbian era-and yet its presence today in our homes, gardens and stores adds warmth and texture to even the most modern spaces. Radiant with the personal touch of individual hands, Mexican molcajetes, metates, morteros and bateas are treasured old culinary antiques that are now being used in new decorative contexts, making it possible for their artistry to touch many generations to come.

Other essentials of daily Mexican life are small worktables and stools. Hearty, functional pieces carved from single blocks of wood, their versatility is proved throughout the home and workplace. The most universal shape-a round disc with fitted legs-is commonly referred to as an escabel, or milking stool. These all-purpose seats are usually carved symmetrically with smooth surfaces; others make use of thicker wood specimens. Some styles include carved handles on one side for easy transportation. Low, round tortilla tables, are recognizable in this way by a small, carved handhold area extending horizontally from the surface.

A kitchen’s table is the center of the room’s activity. The mesa de cocina, or kitchen table, not only serves as the gathering place for meals and celebrations among relatives but also for important family decisions. Tocineras, or pork tables, with their deep-drawer construction, are used in some kitchens for food preparation and meat drying. Drawers on other tables make them useful as sideboards, and sometimes lower worktables are used in both the kitchen and outdoors to assist in other preparation such as soaking hibiscus petals for making refreshing drinks. (Additional background on old Mexican tables can be found in our ” Mexican Style” article.)

Providing a solid surface upon which to grind corn with a stone metate, the mesa de moler, or grinding table, is a unique element popular in the Yucatan that was traditionally used in Maya homes. Carved from one piece of wood, these rustic tables feature flat surfaces with four- to six-inch-thick sides, open ends, and four pegged legs. Used to grind corn into masa (dough), the table’s height and design works well to accommodate two people working metates on each end. Still in use today, these traditional simple tables have made their way into decorative roles in haciendas and contemporary homes. Used in gardens and patios to hold potted plants, they have also been adapted as unique coffee tables and buffet tables.

Tortilla tables, another frequent sight in rural Maya villages, have also made their way into ranches, residences and upscale restaurants. Crafted from tropical hardwoods, the thick rounded tops are hand-hewn from a single piece of wood, and range in size from twelve to twenty-four inches in diameter. Used by Maya villagers to pat out tortillas before placing them on the comal for cooking, the smooth tops are supported by three pegged legs. The shorter heights allow for a kneeling or sitting position while working.

Contemporary Mexican Kitchens

In addition to the traditional kitchens found in colonial homes and haciendas, the contemporary Mexican kitchen has evolved with fresh interpretations of old and new that continue to echo the spirit of Mexico’s culinary traditions. This innovative mixture combines all the familiar elements-hand-painted Talavera-style tiles, rustic wooden tables and everyday utilitarian objects-with modern fixtures and appliances that work alongside old-world elements.

In addition to tiled counters and large venting hoods, kitchens today often mix natural, traditional materials with contemporary fixtures and highly functional polished and colored concrete surfaces. Modern stovetops rest on old-style counters, providing contrast and convenience, and brightly painted trasteros stand across from sub-zero refrigerators.

The kitchen at Casa Reyes-Larrain in the Yucatan is an excellent example of a Mexican Colonial-style cocina that resonates beauty and function through its mix of natural, traditional materials and contemporary design. The kitchen features a fourteen-foot high ventilating hood that is traditional in its shape, yet its elongated proportion and bold blue color make a strong contemporary statement. Created on-site with white cement and lime-based paint, the hood features a unique bas-relief decoration on its lower edge, inspired by a French cement-tile pattern. This pattern, first transferred to a handmade wooden mold, was carefully stamped onto the cement surface while still fresh.

Influences on Mexican Kitchens

The progenitors of many design details found in today’s contemporary homes are Mexican restaurants and their colorful kitchens. Decorated with regional furniture, folk art and practical objects, many small family-owned restaurants in Mexican towns are a treasure trove of local elements and intriguing color combinations. Glazed ceramic platters, baskets, grain measure boxes and old scales combine with casual wall displays of regional folk art such as woodcarvings, toys, textiles and paintings.

Often designed in an open style, the regalia of restaurant kitchens is fully exposed, offering fascinating views of deep horseshoe-shaped counters where preparations are in full swing: tortilla presses are in constant use and giant-sized wooden spoons stir caldos (stews) simmering in large ceramic pots. Guests gather around long wooden tables draped in hand-woven tablecloths, seated on simple backless benches and stools or brightly painted rush-seat chairs.

Culinary Notes

The early colonial period brought a culinary marriage between the native foods of Mexico and the influences of the Spanish influx. In the convents and hacienda kitchens of Spanish aristocracy, native cooks began to blend the foods of the ancient Aztecs and Mayans-corn, beans, chiles, tomatoes, chocolate, pumpkins, wild turkeys, and ducks, along with the Spanish contribution of wheat, rice, meats, cinnamon, almonds, and citrus fruits. In the early colonial days, bread made from wheat was still a new cuisine and was mostly consumed by Spaniards. As wheat consumption continued to gain wider acceptance, hacienda kitchens produced more breads and pastries, however, the indigenous population continued to favor corn in all its forms.

Regional hacienda specialties also developed as cooks experimented with the resources in their area. In the state of Coahuila, a pulque hacienda became renowned for its pulque bread, made with the fermented alcoholic drink extracted from the hacienda’s maguey plants. The state of Oaxaca, today known as ‘the land of seven moles,” was well known for its complex pastes made from the region’s chiles, spices, nuts, seeds, chocolate, and dried fruits.

Today’s haciendas, such as the restored colonial Hacienda Xixim in the Yucatan, are still employing their land’s native harvests for daily preparations. Xixim’s chef, Ruben Dario Yam Lara, makes good use of chaya, the green leafy vegetable native to the Yucatan, just as his sixteenth-century predecessors did, incorporating it into myriad dishes and sauces and steeping it for tea. The hacienda also continues its centuries-old tradition of harvesting honey from its own bees, making jungle honey for breakfast hotcakes. Even the Maya tradition of pollo pibil is still prepared as it was in colonial times-wrapping the chicken in banana leaves to cook in a covered earthen pit.

Recipe from Hacienda Xixim’s Kitchen

Calabasitas Rellenas (Stuffed Baby Mayan Squash)

This recipe is courtesy Chef Ruben Dario Yam Lara, Hacienda Xixim, Yucatan. (reprinted courtesy, The New Hacienda, Gibbs Smith Publisher).

A traditional Maya dish prepared in Yucatan’s colonial kitchens, this dish uses baby wild squash ( mumun kuun) that are indigenous to the Yucatan region and available year-round. Traditionally this dish was served for special occasions and was often filled with meat from the jabalik or wild pigs, that inhabit the monte, or dry jungle in the Yucatan.

1. Preheat oven 10 minutes at 480 F.

- 6 small young squash (calabasitas)

- 200 grams Oaxaca cheese (or Monterey Jack)

Filling

- 1/8 pound butter (1/2 stick)

- ½ pound ground pork (unsmoked leg or shoulder)

- 200 grams salami, chopped

- 50 grams bacon, chopped

- 100 grams chorizo (sausage)

- 1 sweet bell pepper, finely chopped

- 1 carrot, finely chopped

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- dash pepper

- dash salt

Sauce

- 8 tablespoons flour

- 6 cups water

- 2 tablespoons chicken bouillon

- 1 teaspoon shortening

- ¼ onion, grilled

- ¼ tomato, grilled

- 1 whole Maya chile (xkat ik) or sweet bell pepper, grilled

2. Wrap calabasitas in aluminum foil and bake for 20 minutes. Remove from oven and let cool.

3. Prepare filling. Saute on high heat for 3 minutes until tender: butter, ground pork, salami, bacon, chorizo, bell pepper, carrot, garlic. Add salt pepper. Remove from heat. Set aside

4. Remove the aluminum foil from calabasitas and cut a round hole in top of squash. Remove all the pulp. Stuff calabasitas with prepared filling. Set aside.

5. Prepare sauce. In steamer, dissolve flour in water. Add chicken bouillon, shortening, onion, tomato, and chili and cook over medium heat for 5 minutes. Stir constantly until mixture thickens and comes to a boil.

6. Place the calabasitas in steamer and reduce to low heat. Cook 10 minutes longer. Cover the top holes in the calabasitas with cheese.

7. Serve calabasitas in a flat soup bowl covered with sauce.