Fish, farmland or bungee-jump?

This article is Part 4 of Tony Burton’s series:

“Can Mexico’s Largest Lake be Saved?” .

Part 1: May, 1997 – Can Mexico’s Largest Lake be Saved?

Part 2: March, 2000 – The State of The Lake.

Part 3: March, 2001 – The Future of Lake Chapala–Suggestions For Discussion

Part 5: April 2003 – A review of “The Lerma-Lake Chapala watershed: evaluation and management”

It has been reported (El Informador, March 22, 2002) that a likely future scenario is the deliberate draining of 40% of the lake, creating excellent development prospects at the western end of its basin, in the region of Jocotepec and San Luis Soyatlan.

Our correspondent just filed this report:

Place: Ajijic. Dateline: Monday April 15, 2002.

Bad news: Patient worsens; vital signs weak. Team of doctors offers conflicting advice; some favor euthanasia.

The patient is still alive, but may require years of life support. For more than a century, her most earnest admirers have made innumerable sacrifices in order to live by her side. Many have had to make clean breaks with their past and begin again in a new land. All this time, she has endured one abusive relationship after another, never complaining, simply suffering in silence.

The earliest known obituary for Lake Chapala is probably the single line of text, written prematurely back in the 1950s, that became the motto of one of the citizens’ groups fighting for her protection: “When a lake dies, a desert is born”. Unfortunately, her next (and perhaps final) obituary may be needed all too soon.

Why is the patient in such serious trouble? First, several previously reported symptoms have worsened. In addition, the “doctors” (scientists and politicians) attending Lake Chapala have now admitted that she is exhibiting many other signs of distress, and that previously existing health-care provisions can no longer be counted upon to alleviate her condition.

In her low times, when younger, the lake was able to call upon additional reserves of groundwater from beneath the parasitic villages, such as Chapala, Ajijic and Jocotepec, that have spread cancer-like on her shore. But well levels are dropping rapidly (Guadalajara Colony Reporter, March 22, 2002), and less and less of this water is available to replenish the lake. The solution? Dig the wells deeper, further beneath the skin. Extract more water, even if it has to be taken from vital organs at ever-greater depths. Meanwhile (as a short-term and unpopular palliative), “please conserve water” and “take particular care in restricting watering of lawns and gardens to early morning and nighttime hours…”

The inhabitants of Guadalajara are faring just as badly. They have endured water restrictions all year, with a regular rotation of the areas that have their main water supply cut off on any particular day. On top of this, more than 1 million people in the city had no water supply for many hours over Easter while repairs were carried out to the distribution system.

However, SOME people are happy. The farmers on the patient’s southern shore now have more farmland than ever (and I mean EVER) before. By a few centimeters, the patient’s current surface level is the second lowest, after the record low registered in 1955, since daily readings of her vital signs began about a hundred years ago. But, she currently has a greater expanse of desiccated skin exposed on her southern flank, now being grazed and ploughed, than at any previous time in her life. Why? In part, because sedimentation has raised the bottom of the lake since 1955, so that any given lake surface level actually represents less water (in volume) than the same level did previously. Another huge difference is that, while the lake’s drop to her low of 1955 occurred very rapidly, giving farmers little time to adjust to the “new land” that suddenly presented itself, this time her level has been dropping steadily for more than a decade, allowing farmers ample opportunity to realign their fences and extend their domains.

One would imagine that the lake’s official guardian, the National Water Commission, would be very concerned by these developments. But it isn’t. Why not? Because even if its revenues drop as a result of not having enough water left to sell, it can make up the difference from the lease fees it charges to the farmers permitted to work the new fields! This ensures that the Commission has precious little incentive to restore the patient to her former health, supposing it is possible.

Meanwhile the poor patient continues to suffer from severe dehydration. Her desiccating skin is pock-marked with little island pimples that have emerged as the volume of her vital moisture reserves has been reduced. Her outer layer of skin, the shoreline, is no longer smooth and supple, but scarred by shallow marshes which are steadily trapping more sediment and further hastening the drying process. Ringworm-like patches of furrowed farmland are spreading rapidly around her former islands.

And, inevitably, the concentration of the multitudinous toxins – herbicides, pesticides, fungicides, fertilizers, excrement – in her moisture reserves has increased dramatically as the volume of these reserves has diminished. A recent study of 35 water and sediment samples, (published in El Informador, March 25, 2002), revealed the presence of DDT, Aldrin, Dieldrin, Endrin and Lindane, amongst others. The levels were especially alarming in the areas around Tizapan el Alto and San Nicolas. If, or when, the lake enters remission and her level rises substantially again, another problem is likely to present itself. The water hyacinth once covered 17% of the lake surface. It is still lurking in the shallows. Millions of its seeds are waiting on the dried-out mud bordering the lake’s shores for the propitious time when warmth, water and fertilizer combine to stimulate some serious growth. This is precisely what happened following the drought in the 1950s; there is no reason to suppose it would be any different this time around.

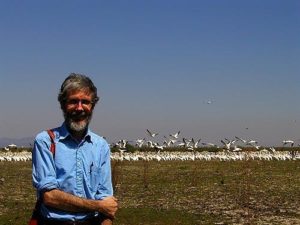

Even animals which have enjoyed a symbiotic, mutually-beneficial relationship with the lake for centuries seem to be re-examining their options. The stately white pelicans are being forced to look further afield for their food. This is exemplified by their repeated flights, in long wavering lines, across the lake and off to the west in search of alternative sustenance, a behavior pattern reported more this year than ever before.

The “doctors” have convened numerous conferences, calling for ever more studies, but the range of symptoms exhibited by the lake seems to be taxing their abilities to agree on a definitive diagnosis and a suitable treatment plan. Even as laboratory technicians work overtime measuring the lake’s vital symptoms in an effort to ensure that all relevant data can be made available to consultants, some onlookers, in despair, have called for outside help. Perhaps someone somewhere has developed a miracle elixir, that could be given, with or without a prescription, to cure all the lake’s ills. So far, this search has been in vain. The good news is that a 3-day conference in February 2002 concluded that the patient IS still alive and might even qualify for membership in the Living Lakes Partnership. Also, the federal environment agency has recently circulated its “master plan” for recharging the aquifers of the Lerma basin and “fully stabilizing” the patient’s condition by 2010, albeit at the staggering cost of 2.4 billion dollars.

As a stop-gap measure, the doctors agreed in late 2001 to give the patient a little more water (270 million cubic meters, equivalent to about 20% of the patient’s pre-existing body fluids) intravenously, along her main vein, the River Lerma. The doctors in charge later decided that the health risks associated with such a rapid re-hydration of the patient were too great for a “single-dose” treatment. Accordingly, nursing staff administered the first 175 million cubic meters intravenously in November, 2001, and are due to inject a further 95 million cubic meters beginning April 16, 2002. Some cynics argue that any delay was primarily because the specialists hoped that the patient would expire prior to receiving this latest (expensive) treatment, a treatment that may prevent some farmers up-river in Guanajuato and Michoacán from being able to irrigate their fields to their usual flood depth in excess of 20 centimeters (8 inches) later this year.

Continuing the patient’s treatment program has the added side-effect of allowing certain influential owners of “lakeside” residences the opportunity to sell their real estate while it can still honestly be claimed that it is possible (with binoculars on a clear day) to see the lake from their terraces. This, say some skeptics, is why the patient’s life will be prolonged a few more months, prior to administering the last rites and then laying her remains finally to rest.

Opponents to the continued expense and hassles associated with treatment argue that the most realistic option, given the current suffering and pain felt by the lake, is to end her misery once and for all. Euthanasia, they believe, is the only humane option. Rather than try and keep the patient on life-support any longer, or performing any major transplant (possibly involving imported technology and costing millions of dollars), they argue that it is simpler to ease her through the pain of her last few days by desiccating her completely. The resulting dust bowl will then be converted, as a lasting memorial, to a major ecological real estate development, with golf courses, multi-storey hotels and country club.

The centrepiece, with a running path for the local Hash House Harriers, will be a series of swimming pools (with purified water) and an artificial lake, complete with fibreglass ducks and plastic pelicans. All water will come from deep wells. So that this development can be clearly distinguished from its unfortunate short-lived predecessor, it will be known as “Eco-Chapala”. This name, highlighting the project’s immense contribution to local ecology, would surely garner considerable international support, pleasing the multi-national sponsors such as Disney, McDonalds, Microsoft and Holiday Inn.

The construction of Eco-Chapala is likely to last several years. During the early phases, the unsightly dust bowl will be completely camouflaged by a life-size eco-painting of the former lake. Besides providing gainful employment for the multitude of starving Ajijic artists who suddenly find themselves with left over paint and surplus ideas, the “world’s largest” mural (complete with details such as windsurfers and birds flying in perfect formation) will guarantee that a beautiful view can be enjoyed (and even painted) from all the surrounding areas. The mural will be a tremendous improvement over Nature since it will (thank goodness) be free of such imperfections as unruly waves, carnivorous fish, the occasional dust storm, birds flying wherever they want, non-ecological floating objects such as water hyacinth or (even) cloudy weather. Eventually the mural will be superseded, during the final stage of Eco-Chapala’s landscaping, by a giant series of programmable “screen-savers”, harnessing the excess computing power and high speed modem connections available in the villages to project whatever landscape the local community desires from any point of Eco-Chapala’s “shoreline”. Different seasons will be enjoyed by all once again, but without any attendant climatic discomfort. Winter scenes of rooftops glistening under a light dusting of snow can be replaced in Spring with colorful displays of daffodils and tulips, followed by tropical forest for summer and full Fall foliage later in the year. What a vast improvement on tired old Nature which only offered one unchanged view all year!

Proponents of euthanasia have one major thing going in their favor. The lake will eventually dry out, whatever we do. So, the real question is, how do we want her to die? If we continue to abuse her, as we have for the past 50 years, she will come to an agonizing end very shortly. Even if we can stabilize her vital signs for another century or so, her long term prognosis is poor, with the possibility of global warming reducing the region’s rainfall and increasing its evaporation. And, if global warming doesn’t finish the lake off, geology certainly will. As an article elsewhere ( Burton, 2001) has described, a new coastline, that of the Pacific Ocean, will (shortly) be arriving in the area. Its arrival, circa 1.2 million A.D., will be heralded by a series of earthquakes, which will cause the western hills close to Jocotepec to drop away into the ocean, releasing a devastating waterfall as any remaining remnants of the lake drain away within seconds. Do we really want such a sudden and ugly death for our patient? Indeed, knowing that this is about to happen, surely we should also be starting to plan an Eco-Pacific Ocean?

Desiccating Lake Chapala would be painless and prevent her demise from any of these other horrible possibilities. Besides being the only humane thing to do, the development of Eco-Chapala would provide thousands of jobs and bring an economic boost to the region. In exchange for giving up fishing rights, the indigenous inhabitants of Eco-Ajijic and Eco-Jocotepec would, in due course, be granted the concessions to develop the world’s most mind-boggling eco-bungee jump and the world’s toughest eco-abseiling route from the top of North America’s highest eco-cliffs down into the warm, placid, and by then osmo-purified, waters of the Eco-Pacific Ocean, complete with its artificial, spouting whales…

Well, really! Why bother preserving the original when WE can clearly do so much better?

[Author’s Note: The inspiration for this article came from reading Julian Barnes’ novel, “England, England”]