The warm afternoon breeze wafts a gentle mist of dust across the floor of the Oaxaca valley and into Oaxaca city, softening the colonial patina of the richly carved, 300-year-old cathedral. The dust is two thousand years old, the dust of Monte Alban, the first major city in the Americas. Now a ghost city, Monte Alban sits perched on a promontory overlooking the modern city which sprawls across the valley floor far below. Two millennia ago, the Zapotec Indians who built Monte Alban trampled part of the hillside into this dust, as they traded in the city’s thriving market or gathered to witness important ceremonies. While they went about their daily tasks, Monte Alban’s resident priests and astronomers were discussing how to achieve two great objectives: where to construct a new, state-of-the-art astronomical observatory and how best to help civic leaders five hundred kilometers away in central Mexico construct another major urban center – a city which was to have huge pyramids and which would subsequently be known by us as Teotihuacan, “City of the Gods”.

Given the long and rich history of the Oaxaca valley, and the balmy afternoon sunshine, is it any wonder that sitting in the city’s main square sipping a cool beer, my thoughts repeatedly turn to what it must have been like in the past and to ponder on possible scenarios for the next millennium, now just around the corner?

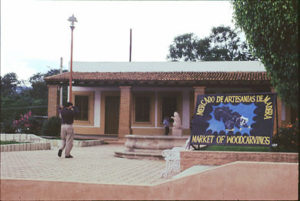

The cities of the Oaxaca valley have welcomed tourists for over two thousand years. Among the earliest tourists anywhere in Mexico were those families who accompanied the traders who came to barter their wares in Monte Alban. In recent times, a flood of tourists from Europe, the U.S. and Canada has flowed through Oaxaca’s airport before fanning out across the valley in search of the vestiges of the ancient Zapotec and Mixtec cities, seeking to find clues to timeless questions in these long-abandoned sites. A steady stream of modern-day tourists scours city stores for indigenous handicrafts; a few tourists trek to the source of these colorful ceramics and textiles, to one or more of a score of otherwise drab Indian villages, each with its own particular specialty and weekly market.

It is sobering to reflect that historians, in a thousand years time, may well depict the period 1000 to 2000 AD as the “age of massive urbanization”. Let’s face it, a thousand years ago, large cities were few and far between. Now, on the verge of the next millennium, more people live in urban areas than rural ones. But the opposite trend is already becoming evident in many places, with some urban residents choosing to relocate to suburban and rural areas on the urban fringe, a movement labelled “counter-urbanization” by sociologists.

Oaxaca is a perfect place to reflect on the ebb and flow of cities. Just a few kilometers west of the modern city, Monte Alban is now a ghost city, inhabited only by archaeologists and visited more by international tourists than descendants of the people who originally lived there. The “modern-day” (post sixteenth century) city of Oaxaca, retains its beauty – a jewel displaying all the best facets of colonial art and culture – but is growing rapidly, some would say uncontrollably. To the east of the city, scattered over the floor of the Oaxaca Valley, are small villages, many dating back to pre-Hispanic times, and several formerly more important settlements, which have now sunk into ignominious obscurity. How did these changes occur? What prompted them? Archaeologists are still striving to unravel the clues.

Past and present merge together during even a brief trip to Oaxaca. In the morning, you can journey from the creature comforts of your twentieth century hotel room to a nineteenth century craft studio, where artisans toil from dawn till dusk, creating imaginative works of art. At mid-day, your lunchtime food can range from such pre-Columbian menu delights as fried grasshoppers to modern fast foods like hamburgers. In the afternoon, visit a museum housing seventeenth century treasures, before climbing the time-worn stairways of an ancient city.

Once in Oaxaca, don’t be surprised if your planned two or three day stay somehow becomes four or five days. There is so much more to see and do here than a single trip can encompass. But even those on a strict “one night only” budget can capture the elusive flavor of Oaxaca by combining a downtown hotel with visits to just three separate sites that lie in close proximity to one another just outside the city, sites that tell stories stretching over thousands of years.

Let’s start by visiting Monte Alban. If you go in the morning, set out early and try to be at the site as it opens (8 am), if only in order to gain a head start on the busloads of multilingual tour parties that arrive each day. The morning light can be very special here and watching the overnight mist dissipate slowly as the sun lazily filters through to the valley floor nine hundred feet below is a magical, almost mystical experience. Afternoons at Monte Alban are often much quieter, though the site closes promptly at 5 pm; allow at least three or four hours to explore the site.

Archaeologists have found evidence that nomadic people first wandered through this region around 8000 B.C. Eventually, the domestication of crops allowed small concentrations of Zapotec Indian families to live year-round in a single place. The earliest villages date back to around 1400 B.C., by which time Mexico’s staple foodstuff, tortillas, have been “invented” and burials have become organized – perhaps so that family members were not lost. Signs of trade appear – of such exotic items as obsidian (for cutting implements, arrowheads and mirrors), greenstone (religious effigies) and shells (jewelry, musical instruments). Gradually the village becomes a small city of 25,000 or so people. Within this city emerge writing, calendars, social stratification and ceremonial functions.

The emergence of Monte Alban as a major city is well illustrated in the fine museum at the entrance to the site. This museum is typical of the sterling nationwide 1990s effort by the National Archaeological and Historical Institute (INAH for its Spanish name) to bring important discoveries and artifacts back to their original homes. After decades when virtually no reliable information was available at Monte Alban, the site museum now provides expertly displayed and up-to-date information on many key aspects of Zapotec life. Particularly impressive are the displays detailing the practice of skull trepanation, where, for unknown reasons, some people had small holes drilled or cut into their skulls. Their healing scars prove they survived the experience, though we have no idea whether their lives were made better or worse as a result of these surgical interventions. Other displays highlight the details of congenital defects and malnutrition and of cultural practices like multiple burials.

The museum, though small, also contains numerous artifacts offering convincing evidence of trade links between the Zapotec residents of Monte Alban and the far flung territory dominated by the Olmecs along the Gulf coast and, in later times, to central Mexico and Teotihuacan. The links to Teotihuacan are especially interesting with the many specimens of the naturally-occurring mineral mica found in that city almost certainly coming from the Oaxaca region and the numerous obsidian items found in Oaxaca just as certainly coming from workshops on the outskirts of Teotihuacan. Moreover, researchers have shown that the city of Teotihuacan contained a clearly defined quarter that is specifically Zapotecan in nature.

Unique to Monte Alban are ceramic funerary effigy urns, some twenty centimeters tall, which have hollows in their top. No ash or anything similar has ever been found in the hollows, so either these hollows served some as-yet unknown purpose or Zapotec cleaning methods were way ahead of their time. Most of the urns have calendric names inscribed on them and show seated male and female deities, complete with clothing and jewelry. Often the effigy represented on these urns is the Zapotec rain god, Cocijo, but bat and jaguar effigies are also common. As anthropologist Peter Furst has pointed out, bats have certain striking similarities to humans. Bats and humans are the only mammals having a single pair of breasts and bats, like humans, normally bear only a single baby at a time. Hence bats form a probable link, via their place of residence – caves – to the underworld, fulfilling the role of messengers and mediators between humans and the underworld.

A short uphill walk from the museum and you emerge onto the corner of an extensive grassed square or plaza, with stairways, temples and constructions on every side. In all, the site covers some 20 square kilometers, spreading over five interconnected hills.

Even a cursory exploration of Monte Alban takes at least half a day, and involves plenty of hiking and climbing, so come prepared with sunscreen, ample water and snack food. For those who prefer a sit-down meal, there is a more than adequate cafeteria at the site entrance. Of course, whatever you do, don’t forget your camera.

Next time, we’ll take a walk around the site and journey on to Cuilapan, Zaachila and Arrazola.

How to get to Monte Alban.

The walk from downtown Oaxaca is about nine kilometers each way. By car, go west along the Periférico (or “ring-road”) at the southern edge of the city, cross the Rio Atoyac, bear right and look for the signs. Monte Alban is about six uphill kilometers away. Daily tourist bus and minibus tours leave downtown hotels. Enquire at the front desk. Frequent regular buses to Monte Alban leave from the bus terminal near the Abastos market, west of downtown, where Trujano street intersects the Periférico. Taxi fares for a private cab to the site are inexpensive.