February 4, 2002

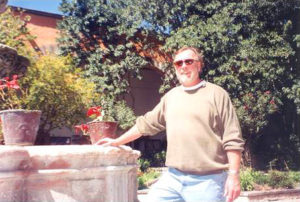

It all began on Monday morning, one day before Constitution Day, in the Jardin, the local square, of San Miguel de Allende. My wife constantly reminds me that I am obsessive, and she is right. I feel that the only way to live is to have a question before you that needs answering. My current one is to find out any local insights into and information about Neal Cassady, aka “Dean Moriarity” of On The Road fame who lived out his last days and died in San Miguel. I realize there are a multitude of web sites and literature available, but my objective is to hear from some people, in their own words, who might have known or known of this fascinating guy.

So I’m alternately sitting on a bench staring at that huge, pink wedding cake of La Parroquia, an immense Gothic church, or roaming El Jardin (the garden park that fronts the church) wondering where to start. At the end of my second circuit, I sit down next to a guy. He’s holding an unlighted cigarette in his hand. He gets up and walks a few feet over to a lady and asks her for a light, which she provides. In the course of igniting, his hands are shaking so badly that this act becomes more complicated than firing up the Olympic Torch. He comes back and sits next to me.

I lean over and say; “You look like someone who knows his way around here.”

“Why do you think that”?

“You just do,” I reply. “I’m looking for where Neal Cassady lived. Ever hear of him?”

“Nope.”

“He was a friend of Jack Kerouac’s, a major influence on him, and the model for a character in On The Road.”

Jimi, as I later find out to be his name, looked like an even more razor-thin reincarnation of the late actor John Carradine. He told me he wasn’t usually in the Jardin at this time in the morning unless he had been drunk all night, which he had. Yet his shirt was stylishly western, his pants sharply creased and his boots burnished to a glow.

I tell him the little I know about Cassady, and that I want to take a picture of the last place Cassady lived. Jimi is really straining to come up with something. “They used to drink at the La Cucuracha,” I say. He jumps on this news. “See that corner,” he says, pointing to the northwest, “that’s where it was, where the Banamex bank is. The new place, same name, is down on Zacateros.” With all of the rigidity of a thesis advisor, he tells me it wouldn’t be fair to include the new place in my research since Neal and Jack had never been there. I had to agree.

“Stay here,” he says, I’m going to ask around.” I watch him approach a bench full of late middle-aged guys, talk to them and then gesture back at me. Finally, he waves me over. Jimi introduces me to “his family,” as he collectively describes them, as a “scholar.” A few nods are granted but no names are exchanged. One guy knew a Cassady from Canada. “Not him,” I say. Suddenly it dawns on me. I’ve been giving out the wrong year of his death. He died in 1968 not 1960 as I told them. But they didn’t seem to know the difference as each one wracked his faultily wired memory box for a trace of recollection. One of the bench occupants, Shanghai, owned the apartments where the others rented, including the now departed Jimi. Shanghai opined that he had read On The Road and “the only thing I learned from Jack was never to use punctuation again.” He thought Bill Conway might know something but no one had seen him for two years.

Dave, a former contractor from Grand Rapids, Michigan, had been here off and on since ’61 but said there were so many drunks passing in and out of here that it was impossible to keep track of anyone. He did tell me that he used to know Howard “Hopalong” Cassidy — not the cowboy, but the All-American, Heismann Trophy-winning running back for the Ohio State Buckeye national championship team. I told him I was from Ohio and remembered Hoppy when I was in grade school. Turns out that Dave knew him when he played for the Detroit Lions. Then we established a further commonality of interest since I have a summer home in Paw Paw, Michigan and had two conversations with local legend Charley “old Paw Paw” Maxwell, formerly known as the “Sunday home run hitter” for the Detroit Tigers.

Then in not a stream, but rather a gusher of consciousness, Dave went off on a tale about Mickey Stanley, another Detroit Tiger ball player. It seems Stanley bought several hundred acres by Lake Michigan and wanted Dave to punch a road through them. Dave needed a bigger bulldozer for the job so Stanley took him to a huge parts yard near Detroit where Stanley knew the owner. Apparently, the owner of the yard kept a furnished upstairs room where the pro athletes of Detroit came to drink in private. That’s where he met Hopalong Cassidy, and anyone of a certain age in Ohio will tell you that “Hop” was no stranger to liquid refreshments.

No mention if the road was ever built or the whereabouts of Neal’s former residence.

Everyone did recall the writer who wrote and drank all day at the San Miguel American Legion bar. He wrote True Grit there. I chimed in that he was Charles Portis and I had an autographed copy of the paperback edition of it. Not much of a response to that. But it was true. My former teaching colleague Morris Parker was a friend of Charlie Portis back in Little Rock, Arkansas. He mentioned to Portis that I was teaching his book to high school sophomores. Charley sent me a copy and a note thanking me. The location of Cassady’s digs is sinking further beneath the surface.

Where Neal Cassady lived in his last visit here might be published in some source, but I repeat that what I wanted to hear were actual words and directions from someone that knew him and remembered him. For god’s sake, this guy busted loose the literary voice for one of the most significant novels of the past century! He’s had his own stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Department! Someone has got to know where he crashed!

The bench left me with these suggestions: See Archie Dean, the editor of Inside San Miguel, don’t go to the U.S.A. Consulate – an old guy there charges you for answers, and stay away from Mexican bars – any place with swinging doors.

February 5, 2002

Neal Cassady died on this day thirty-four years ago.

February 6, 2002

I begin the day at the Biblioteca Publica on Insurgentes Avenida and approach the first English speaker I hear, who is Chuck. a volunteer in the gift shop. He thinks Neal Cassady’s name “rings a bell,” which is understandable phraseology in this small municipality of multitudinous churches and chapels where pealing has been raised to an art form. He did suggest that I call the PEN Writers Association, as if Cassady ever belonged to anything or would know anyone who did. Next stop was at one of the librarian’s desk where I encounter the very kind Juan Manuel Fajardo Orozco, who likewise knew nothing about Neal Cassady, but spends a lot of time making sure I spell his name correctly. Señor Fajardo gives me the name and phone number of one Lucina Kathmann, the current president of the local PEN chapter. I never did call her.

Back to the Jardin (also known as a zócalo or public square in every other Mexican town), I check in with Grand Rapids Dave. He has a good lead for me in the person of one Tom Frazee (Dave couldn’t spell his last name, but assured me it rimed with “crazy”). Tom is an erstwhile theater guy and a locally noted stained glass window maker. Dave said he talked to Tom at the Agave Azul bar and told him who I was looking for. He suggested I hit the happy hour between five and eight to see if Tom could help.

I made happy hour at 5:20 pm and struck up a conversation at the bar with a guy named Jeff Arnold, a 54 year old recent retiree from San Antonio, Texas. I told Jeff what I was up to, and he said, “You are not going to believe this, but when I was fourteen, in 1961, I delivered Neal Cassady’s newspaper to his house in Milbrae, California.”

“What was he like?”

“That’s my bad news. I never laid an eye on him. I think he was split from his wife Carolyn then. But the Hudson Kerouac wrote about was parked in the front of his house.”

Jeff even knew all of the railroad yards south of San Francisco where Cassady was a train brakeman. Jeff’s high school English teacher was Gordon Lish, who eventually founded and edited Genesis West literary magazine and The Quarterly and hung out with the Beat crowd at the City Lights bookstore. My new friend was amazingly well informed about the Beat Movement and its participants.

We were joined by my wife Jerri Rae and then by a Mexican landscaper named Cris who had been raised in the U.S. by an adoptive father. He revealed that his full name was Cristobal Scott MacGregor Hidalgo. His birth father was from Scotland and his mother bore one of the proudest names in all of Mexico. Cris skirted around his first marriage but recalled living with her in Arlington Heights, Illinois and working in Naperville. He referred to his last girlfriend as his “potentially second ex-wife.” No Neal input from him.

Then in pops one Rich Bannister who used to live in San Miguel but left in 1976. He had just bused in from Playa del Carmen and was astounded by the room rates. Like everyone else in San Miguel, he had a book manuscript in his luggage; well, actually, twenty-one tapes of reminiscences and all the letters he wrote to his mother from Vietnam. Cris phoned around and found him the cheapest room on the planet, 225 pesos a night (25 USD). We bought him a few drinks and he told us he had once met Allen Ginsburg in Spain. This was an evening from The Sun Also Rises.

February 7, 2002

In what is fast becoming a ritual, I meet Grand Rapids Dave at the Jardin to report my progress. It seems that Dave is really getting into this largely undefined search. I told him no Tom Frazee sighting last night. He said: “Not to worry. I saw him last night and got his card for you with his phone number.” The only problematic thing in dealing with Dave is his short-term memory. As I was leaving him, he said, “Oh, there’s one more thing.” And he proceeded to tell me a tidbit of information that I had told him yesterday! Hey, you work with the sources you got.

Dr. Mortimer Stith, local resident and professor emeritus from University of California, whose lecture on Mexican mythology I would attend tonight, happened by. He patiently listened to my somewhat disjointed explanation of what I was doing. He then drew his eighty-two year old frame to its fullest height and informed me that he knew why Neal Cassady had been here — “cheap drugs, obviously.”

Later this afternoon, a twenty minute phone call with Tom Frazee turns out to be a bonanza of leads. He has just started a web site, www.intrepidtraveler.com that contains Cassady material. Trying to stay with my original premise, I ask him for some names of people with whom I might speak. He suggests Dan Ruffert, an artist, Rudy, a teacher at the Instituto Allende, and Ed Osman, another artist. All should possess some information and, viola, “I’m sure Dan Ruffert used to live in Cassady’s last apartment,” Tom belatedly reveals.

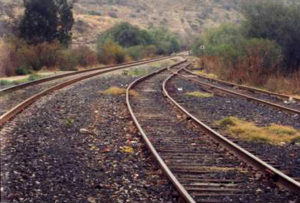

To detour slightly, most sources agree that Neal Cassady, on the cold night of February 4, 1968, while pumped up with Seconal and pulque, announced that he would walk the railroad tracks from San Miguel to Celaya (about 15 miles) for the expressed purpose of counting the railroad ties. Clad only in jeans and a T-shirt, he passed out on the tracks, was discovered the next morning in a coma and died the same day. Legend has it that his last words or numbers were “64,928,” allegedly, the ties he had counted. Let’s chalk that figure up to “mischievous to the end.” To this information, Tom had added something interesting. “Go to the KOA campground by the tracks and see if you can find an old-timer to show you the exact spot.”

February 8, 2002

After touring a glass blowing factory in the morning, Jerri and I rendezvous with Shanghai and Dave in the Jardin around noon. I thanked Dave for Tom’s input and told him I would see Dan Ruffert around three o’clock that afternoon. Apropos to nothing, Shanghai suddenly reveals that he just talked to the supposedly missing Bill Conway’s wife. “I’m not even going to try to direct you to his house,” Shanghai said, “but you can find him any day at the Los Gatos Negros bar.” He also established that this was not a “swinging door” bar, but was safe to enter.

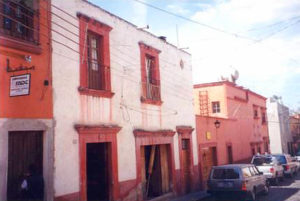

Dan Ruffert, whose art gallery is in the Taboada on Cuna Allende, had, indeed, lived in the last apartment inhabited by Neal Cassady in 1968. He moved there in 1974 and remembered that people were still knocking on his door looking for Neal Cassady six years later. One Englishman came by who was trying to retrace Cassady’s footsteps across the U.S.A. and Mexico. From what Dan had heard in town and could remember, it appeared that Neal Cassady was in a real decline and not thought of too highly. It seems like he spent most of his time hitting upon his friends’ wives. But I’ve got the address — #15 Beneficencia. Go west on Canal and take the first right past the Quebrada Bridge.

Had he lived, Neal Cassady would have been 76 years old today.

February 9, 2002

#15 Beneficencia is easy enough to find. It is a two story whitewashed structure trimmed in pink. I photograph the house and address several times from the street. The building’s owner maintains a carpenter’s shop on the first floor. He assures me that it is okay to ring the bell and inquire of the tenants. I do so and am invited up the stairs to the apartment that covers the entire second floor. I try to acquaint the gracious and charming Glenda Xochitl Torres as to my purpose and she asks me in perfect English if I am Neal Cassady! So much for the clarity of my explanation! She invites me to look around and take as many pictures as I like. Among others, I take a picture of Eric, age four, in his bedroom and one of two year old Aida and Glenda together. We chat about where I am from and how long I’ll be here. She asks me to send her a copy of whatever I write and I promise to return with the pictures.

February 10, 2002

As if to show in what kind of weather Neal Cassady died, Sunday night brings a thunderstorm and a record low temperature of 35 degrees F in the morning.

February 11, 2002

I begin my class on “Aspects of Mexico” this morning at the Instituto Allende. My instructor is Rudolfo Fernandez Martinez Harris, dean of students and co-owner of the school. Bronze busts of his parents, founders of the language school, are enshrined in the courtyard. My teacher is the “Rudy” that Tom Frazee told me to look up. He, too, has heard of Neal Cassady but was too young in 1968 to know him. After class, he recommends I talk to Barbara at the El Correo restaurant across from the post office. On my way home, I stop at Dan Ruffert’s studio and tell him I visited the apartment and thank him for the lead. He is packing up paintings for an exhibit in Puerto Vallarta. He takes my phone number and says he’ll call me when he returns in a week, if he can think of anything else. Before I leave, I ask him where the railroad station is. “Go straight to the end of Canal,” Dan says.

“Where is the KOA campground in relation to the station? I heard he died close to there.”

“No,” Dan says. “The Englishman established that he died about two hundred meters down the track from the station. He piled up some rocks off to the side and planted a little wood cross. That was twenty-eight years ago.

I mention Barbara at the restaurant and Dan says, “She’s Rudy’s half-sister.” For whatever reason, things seem to be only partially revealed, a bit at a time, in Mexico.

Ed Osman, whose art studio is just above Dan’s, tells me that everyone from La Cucuracha that he knew is dead and he only vaguely remembered hearing about Neal Cassady. He suggests I call Tommy Andre, a retired bullfighter, who might be able to help. La Conexion Message Center gives me his phone number and we talk. It turns out that, during those years, Tommy fought the bulls out of town and only infrequently returned to San Miguel.

A return visit to the Torres to give them the kids’ photos turns out to be the bonus of this whole undertaking. Glenda’s husband Alex is just getting ready to go to work. He is the piano player at La Capilla, the second fanciest haute cuisine spot in town. Also at home is twelve-year-old Rita. They welcome me and thank me for the pictures. Both ask if I want something to eat, and seem very comfortable calling me “Jim.” I mention that Cassady used to enjoy the apartment’s terrace. But I didn’t see one. (I later learned that there had been a terrace but it had been removed.) Glenda said he must have meant the roof and showed me the ladder where they climbed up to sit sometimes. They invite me to come back again before I leave and to bring my wife. The humbleness of their home only emphasizes the breadth of their hospitality. After, only two visits, I really feel I know a familia in San Miguel.

February 12, 2002

Rudy leads our class on a field trip to the Allende Museum and then to study the indigenous pagan artwork cunningly placed on the facades of several churches under the not-so-sharp eyes of the Spanish clergy. On the way, we stop for coffee at El Correo, his sister’s café. Barbara Dobarganes concludes that too much time has elapsed and just about all probable links to Neal Cassady are forgotten, gone or dead. She has been here for the past forty years, but seems to have traveled in a better circle than that rogue, Cassady. We both agree that a death certificate had to have been filed here and that it would be a valuable document to have. Next stop will be the Federal Oficina del Gobierno del Estado, just a block over from the restaurant. I’m to ask for Judith Gonzales and say Barbara sent me.

After class, I show Rudy the following sentence I have written in Spanish: “I need a death certificate for Neal Cassady, Jr. who died on February 5, 1968.” I am so proud that I have translated “death certificate” into certificato de muerto. I ask him to write out the whole sentence in Spanish for me. He says, “there’s a slight problem here. If we use your sentence they are going to ask you where the body is. Then they’ll ask you why you have kept it since 1968.” My request becomes Necesito una copia del acta de defunción de Neal Cassady, Jr. quien murió el 5 de Febrero de 1968. Armed with this note from my teacher, I prepare to assault Mexican bureaucracy.

February 14, 2002

At 7:25 am I take my place in line at the government building. There are 24 Mexican adults and eleven babies wrapped in rebozos in front of me. Three toddlers roll on the floor. Eventually the line behind me will snake around two corners. Soccer or futbol is wrongly assumed to be Mexico’s national pastime. Having babies is their national obsession. No wonder the Pope loves Mexico. I’m a head and a half taller than everyone in line. “Who is this gringo, and why is he here?” This question, of course, goes unasked as the line, a study in passivity, stares straight ahead. Suddenly, I’m approached by a slightly goofy looking, but smiling, teenager. “Nombre?” he asks. “Jim,” I reply. “I’m Martin. What are you doing here?” Pretty good English on his part. I try to explain, but he really isn’t all that interested. “Too many gringos in San Miguel,” he says. “How many do you see in this line? Stick around, amigo,” I tell him,” I may need you later.” He gives me what seems to be an abbreviated Latin Kings gang handshake and I resume my wait. The doors open at about 8:15 am. It appears that people are here to deal with minor legal problems and to register births. Two young women in matching slacks and blazers move along the line and examine whatever documents each person has brought along. I gather they are determining if each person has all that is needed to complete the task. Their politeness and their careful explanations, especially to the farm folk, the campesinos, who are awed by the surroundings, are touching indeed. These two clerks are devoid of officiousness.

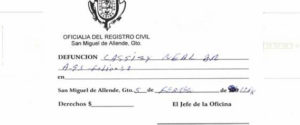

One comes to me and I hand her my written sentence. Un momento, por favor, Señor. She leaves and shortly returns and repeats her statement. In another minute a man comes out and hands me a 5×7 piece of paper. That’s it! It bears the title Oficialia Del Registro Civil and the seal of the office. The next line begins Defunción and Cassady’s full name appears, handprinted, followed by “A-93-folio-32,” followed by the date of death and stamped with the signature of Lic. Judith Gonzalez, Jefe de la Oficina.

No cause of death is given. Later, the hospital where he died informs me that, according to law, such a report cannot be released to the public.

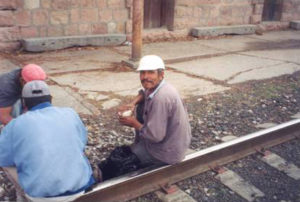

A couple of hours and sixty pesos later, I am at the train station at the end of Canal, on the edge of town. After establishing with the cab driver that Celaya lies to the south, I pace off 200 meters (taking care to make each stride exactly 39.37 inches!) down the track. The waiting cabbie stares at me, dumbfounded. I take a picture of the rails where they curve out of sight and one of the mountains in the distance. Finally, I photograph the ties and rails at my feet. I look across the tracks and find people staring at me from their doorways. Again the question “What is the gringo doing here?” goes unasked. I approach them. One lady has a little English. I stumble through “hombre, muerto, Neal Cassady,” and keep pointing toward the tracks. The older woman nods affirmatively, but the younger woman indicates that she is “loco.” A teenage boy says Americans live in the last house. We all go there, but no one is home. The kid runs and gets a laborer who is working further down the track. In fluent English, the guy asks what I want. I tell him. He asks when it happened. I tell him thirty-four years ago. He shakes his head and says, “You waited too long, Señor.”

Grand Rapids Dave has gone back to Michigan or maybe Oklahoma City for a while. Shanghai needed an apartment for a friend for two weeks so he gave Dave $200 to temporarily vacate. I have violated the strict admonition about “swinging doors” saloons and have gone to the Los Gatos Negros bar three times looking for Bill Conway. No sign of him. I haven’t seen the wraith-like Jimi since the first hour of my first day in the Jardin. I’m beginning to wonder if I really met him. Jeff Arnold has stopped seeing us since he had a total drunken meltdown at our house about a week ago. Just yesterday, I passed a guy walking on the other side of the street and he waved at me. I went over and introduced myself and said, “We ought to meet. We’ve been waving to each other for two weeks.” “I’m Jerry. Jeff Arnold told me about you. I’ve been asking about Cassady all over town for you.” He asks me for a copy of the death certificate for his son in Omaha. No wonder everybody I talked to says that another guy seems to have the same project in mind.

February 18, 2002

Sue Beere, the editor of Atención, San Miguel’s weekly English paper, graciously provides the final word for me on Neal Cassady. A thirty-year resident, Sue, lived with noted photographer Peter Olwyler for the last eighteen years of his life. He passed away on December 7, 1999. He was a good friend of Neal Cassady’s and he described him to Sue as ‘physically in great condition, but with a ravaged face.” Peter also told her that Cassady was on his best behavior around him and his friends. To the best of her knowledge, he never photographed Neal Cassady. The authorities called Peter Olwyler, Sue said, on the morning of February 5, 1968, to identify Neal Cassady.

Neal Cassady came to San Miguel de Allende for the last time in late 1967 or early 1968 pursuing a young female art student. Consciously or not, I think he was ready to die as he was running out of second acts. His association with novelist Ken Kesey and his designated driver status of the Merry Pranksters’ psychedelic bus had replaced the notoriety of him and Keroauc, but that, too, had ended. From what she had heard, Sue Beere concurred with this conclusion. One cannot conceive of Neal Cassady in old age. His cause of death was probably hypothermia. He was cremated here and, fittingly enough, an ex-girlfriend came to Mexico to claim his ashes and return them to his ex-wife Carolyn. A note on the box said: Contiene cenizas de Neal Cassady, Jr.

This man, who never published a word in his lifetime nor ever profited a penny from anyone’s work, has been attributed literary cult status after his death, just three days shy of his 43rd birthday.

Tony Cohan, a resident of San Miguel de Allende and the author of On Mexico Time, concludes, “Sometimes I think of Neal Cassady, whose Road of Excess, ended not in William Blake’s “Palace of Wisdom” but face down on the railroad tracks outside of town. Maybe there’s no home really, only road’s end.”

Cassady, Kerouac, Kesey, Burroughs and Jerry Garcia have all come to their road’s end, but much suggests that the interest still stirred by Neal Cassady’s life, an art form uniquely his own, may well continue to intrigue, perhaps even longer than the artistry of the others.

Luis Alberto Urrea and I are looking for the exact spot, maybe an impossibility, where Neil died. Our obsession is to put up a plaque to commemorate him. I have walked the 200 yards several times trying to establish this. Any ideas for us.

I have absolutely no idea but perhaps some other alert reader will have a suggestion or two.

Your article makes me think I’d like to know where Charles Portis lived in San Miguel. A number of sources tell us that his True Grit was written here. Did he come here frequently? for how long? who did he hang out with? where did he live? His residence too deserves a plaque to commemorate the writer and the book.

Sorry, but I’m unable to answer your questions. Portis apparently became a regular visitor for several months at a time, but I’m not sure when he first visited. Hopefully someone with more knowledge about San Miguel will respond with more details.

Charles Portis lived at Terraplen No. 41 for several months in 1967, possibly working on a first draft of True Grit, though he wrote most of the final version in an apartment on 18th Street in Little Rock, Arkansas, USA. True Grit was published in 1968. He lived at 80 Diez de Sollano y Dávalos for a few months in 1969 to escape the hoopla of the first film version. In 1970 he was at the Hotel Vista Hermosillo for a short time before heading south in his pickup truck to see more of Mexico. He returned to San Miguel several times in the 1970s and ‘80s for short visits.

Jonathan, Many thanks for taking the time to answer previous questions about this article, and for sharing such valuabale additional information. Best regards, Tony.

Great work! Thanks for posting your investigations. Very interesting and ingested with a dose of pathos. I hope Neal’s spirit lingers where he was most happy. A true original.