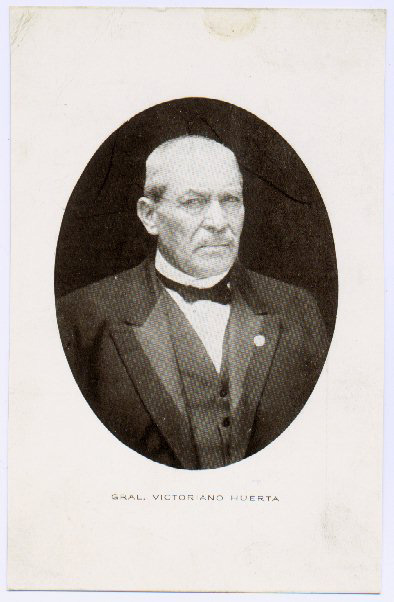

Victoriano Huerta was a man almost too bad to be true. Described by one historian as an “Elizabethan villain,” he was a drunkard and repressive dictator who guaranteed himself a permanent spot in Mexico’s hall of infamy by overthrowing and then conniving at the murder of the liberator Francisco Madero.

Yet one can go too far in blackening the name of a man who did such an excellent job of blackening it on his own. The image that has come down of Huerta is that of a classic “drunken Indian,” a savage who cuts a murderous trail of destruction before he is finally driven from power by more virtuous men. Such a perception is completely inaccurate. Huerta was an Indian by birth and a drunkard by choice — but he was far from being the illiterate brute of his detractors’ imagination. An able and competent professional soldier, he excelled in astronomy and mathematics at the Military College and was also skilled as an engineer, cartographer, surveyor and railroad specialist. He studied Napoleon’s campaigns and some of his own were models of planning and execution. Huerta’s abilities were recognized by some of his worst enemies. Pancho Villa, whom Huerta tried to execute, was sexually lecherous but abstemious when it came to alcohol. (He shot men he found drunk on duty.) Yet he always conceded that el borrachito (“the little drunkard”) was a first-class military man.

Huerta was born in 1845 at Colotlán, in northern Jalisco, land of the Huichol tribe from which he derived. Though he was said to be distrusted and disliked in his native village, he learned to read and write early on and showed every sign that he was going to adapt successfully to the white man’s world. His abilities were soon recognized and as a youth he served as secretary to Donato Guerra, an old-line juarista general known for his distrust of civilian authority.

After graduating from the Military College, Huerta distinguished himself in campaigns against the Yaqui Indians in Sinaloa and the Maya in Yucatan. The fact that he was an Indian himself did not prevent him from suppressing local indigenous uprisings with the utmost ruthlessness.

Huerta greatly admired Porfirio Diaz, another Indian who had succeeded in the outside world. When Diaz was overthrown, Huerta commanded the honor guard that accompanied him into exile. On bidding farewell to the old dictator, Huerta was moved to tears.

Huerta’s relations with Madero are of interest as a contrast in personality, background and style. Huerta was an Indian and Madero of European ancestry. Huerta came out of rural poverty while Madero’s family was one of the richest in Mexico. Huerta was a heavy drinker and Madero a teetotaler. Huerta was “as suspicious as a rat” (in his own words) while Madero’s excessively trusting nature turned out to be the major cause of his downfall.

Madero entered Mexico on June 7, 1911. In October of the same year he was elected president in an honest election with a percentage higher than ever registered in even some of the more notorious rigged elections. Yet within six months he was in serious trouble. Pascual Orozco, one of his chief lieutenants in the struggle against Diaz, went into rebellion in March 1912 because he believed that Madero had slighted him. (Orozco wanted to be governor of Chihuahua.)

Subsidized by the Chihuahua cattle barons and William Randolph Hearst (who feared Madero might seize his properties in northern Mexico), Orozco was hardly mounting a poor man’s rebellion.

A federal force sent against Orozco was beaten so badly that the commander committed suicide. So Madero reluctantly turned to Huerta. At first he had balked — he disapproved of Huerta’s drinking — but was persuaded by one of his advisers who pointed out that General Grant’s fondness for the bottle never impaired his ability as a commander.

Huerta’s campaign against Orozco was a model of well-executed efficiency. He defeated Orozco in five consecutive engagements and in September the badly beaten rebel leader crossed into the United States. Expecting to be hailed as a hero, Huerta was infuriated when asked to account for funds he had received for the campaign. Haughtily replying that he was not a bookkeeper, he began laying plans for Madero’s overthrow.

This was the background to la decena trágica, the Ten Tragic Days of February 1913. During this period there was a murderous artillery duel between Huerta’s forces and those of Felix Diaz, the old dictator’s nephew. Despite terrible civilian casualties, this was a sham battle staged between Huerta and Diaz, who were actually in cahoots. The plan was to create a state of chaos that would pave the way for the removal of Madero. Huerta would then become president and name, with Diaz’s approval, a new cabinet. After serving his term, Huerta would support Diaz as his successor.

Another active conspirator in the plot against Madero was the U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson. In a truly unholy alliance, America’s worst ambassador teamed up with the man who would become Mexico’s worst president. Wilson and Madero detested each other and the dislike had a strong personal basis. Wilson, a lawyer and sometime publisher who represented big business, characterized the idealistic Madero as a “disorganized brain” and Madero, complaining of Wilson’s “impertinences,” said he would ask president-elect Woodrow Wilson to remove his obnoxious namesake because “this Henry Lane Wilson is an alcoholic.”

A shared love for strong waters was undoubtedly a bond between Wilson and Huerta. Both regarded Madero with the distaste of a barroom bully for the prissy Sunday school teacher who doesn’t drink.

Madero was arrested in the National Palace on February 18 and shot four days later. Though Wilson loyally backed Huerta’s version that Madero had died in a crossfire between his captors and would-be rescuers, it was a story about as believable as the “confessions” of defendants in the Stalin Purge Trials of the 1930s.

Huerta’s rule over Mexico lasted between February 1913 and July 15, 1914, when he was forced to resign and go into exile. During this entire period he was trying to fight off a rebellion in the north mounted by Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa and Alvaro Obregón. So it is hardly surprising that his regime was one of terror and despotism tempered only by chaos. Eighty-four congressmen were imprisoned, several were murdered, and a courageous federal senator from Chiapas, Belisario Dominguez, was taken into a garden and shot after denouncing Huerta’s tyranny. As for Huerta himself, he was frequently seen in cafés, heavily guarded, swigging down copitas of the brandy to which he was so partial. (A joke circulating was that Huerta’s two best foreign friends were named Hennessy and Martel.) During this nightmare episode one of Huerta’s chief allies was Pascual Orozco, the Chihuahua adventurer he had beaten so badly in 1912. Huerta and Orozco reconciled and Orozco was put in command of a militia known as colorados (“Red Flaggers”) which staged a savage reign of terror against Huerta’s enemies in the countryside.

Exile for Huerta did not mean inactivity. After brief stays in Spain and England, he came to the United States in April 1915. World War I was then raging but America had not yet entered the conflict. By now Huerta was deeply involved in intrigues with German agents, chief of whom was the notorious spy and saboteur Franz von Rintelen. The plan was for the Kaiser’s government to finance a movement by Huerta and his followers, including Orozco, to return to Mexico, overthrow their enemies and set up a pro-German government. Huerta and his entourage, who had occupied a mansion in Forest Hills, now moved to Texas. But U.S. authorities had got wind of his machinations. Huerta was arrested and confined to the Army post at Fort Bliss near El Paso. There Huerta’s long career of alcoholic abuse finally caught up with him. On January 13, 1916, the old villain died of cirrhosis of the liver.

There’s an interesting footnote to this story. Shortly before his death, Huerta received a sympathetic wire from his former henchman Henry Lane Wilson. In it Wilson expressed the concern that Huerta’s illness might have been caused by mistreatment at the hands of U.S. authorities. He should have blamed Messrs. Hennessy and Martel.