Arts of Mexico

When we talk of Mexico’s great painters, Francisco Goitia isn’t the first name that comes to mind. Yet, without a doubt, he is one of last century’s great painters. He the spirit of his times and reflected the hearts of his people with love and passion.

Francisco Goitia was born in Fresnillo, Zacatecas on October 4, 1882. His mother died in the process of giving birth to him, but he developed a close attachment to Eduarda Velasquez, the woman who nursed and raised him. His father, of Basque origin, was the administrator of a large hacienda, and the young Goitia ‘s early years were spent in close contact with nature. Those years, embedded in his memory, greatly influenced many of his future paintings.

In 1896 he set off for Mexico City to study art at the San Carlos Academy. There, he came under the influence of many of Mexico’s best artists who were teaching at the academy – Jose Maria Velasco, Julio Ruelas, German Gedovius, and Saturno Hernan. He also came in contact with Rufino Tamayo, who was to become a close friend, and the Mexican modern art movement, all of which was to influence his style.

With financial help from his father, Goitia left Mexico for Barcelona. He attended workshops, visited museums, and did many drawings of the city. His skills continued to develop under the supervision of his teacher, Francisco Gali. The quality of his work earned him an exhibition in Barcelona, and the local museum acquired a collection of his drawings.

The work he did in Barcelona earned him a scholarship from the Mexican government. The money enabled him to settle in Rome in 1907 to continue his work and study Renaissance painting and classical architecture. He exhibited in Italy with success and received an award for his work.

A curious aspect of his life in Italy was his fascination with moonlight. He took to painting at night until it was rumored that a ghost walked the streets between midnight and 3:00 in the morning. The village where he had settled thought he was strange, but they found him unobtrusive. This may, however, have been foreshadowing of his growing eccentricity.

With the fall of Porfirio DÍaz, Goitia lost his scholarship and had to return to Mexico. This was 1912, and there no work to be had in Mexico City. He spent his time observing. He did nothing but take notes. Until his return, he belonged to the landowning class, and he didn’t have any point of view about the Revolution.

Finding no work in Mexico City, he returned to Zacatecas where he joined the revolutionary army of Pancho Villa as the official painter of General Felipe Angeles. This started the social education of Fransicso Goitia. He went everywhere with the army. He saw Pancho Villa defeated. He saw misery and disease everywhere. It moved him. He began to feel a profound connection with the common people in spite of his class. He lived among them and wore the clothes of a mule driver. At one point though his few possession were stolen, he didn’t want the robbers caught and killed.

“I went everywhere with the army, observing. I never carried weapons because I knew that my mission was not to kill”, he said. His weapon was the brush. He painted many heart rendering landscapes that reflected the death and desolation of the times. It was during this time while painting the horrors of war that he painted “The Hanged and Disembodied Men”. It is a moving statement to how deeply he felt the devastating legacy of war.

Upon the triumph of Carranza’s forces, Goitia returned to Mexico City. He was immediately commissioned by Manuel Gamio to make a study of the early inhabitants of Teotihuacan. Gamio was an archeologist who believed in a national art. He stressed the need to know and understand indigenous cultures and to systematize that knowledge in order to achieve a synthesis of the aesthetic criteria of the different social groups that had inhabited the country. Many specialists participated in the project – anthropologists, historians, architects, biologists, and photographers, and painters. Goitia was one of them.

As a result of a series of lectures given in the Carnegie Institute in Washington D,C, by Manuel Gamio, an exhibition of Goitia’s paintings were shown in 1924.

Goitia remained with the project from 1918 to 1925. He said he went to “seek the heartaches of the race through its past and to present its suffering”. He sketched archeological sites and objects, and his association strengthened his love of his roots and his connection to the indigenous people. In 1925, he went to Oaxaca to study in more depth the Indian race.

Until he started working on the Gamio project, his work as a painter consisted mostly of experimentation and study. The Witch and The Tremendista, both painted in 1916, were in an exaggerated Symbolist style. They can be seen at the Goitia museum in Zacatecas along with The Hanged Man painted in 1917. These works already shows his taste for the somber.

He found the inspiration he needed in the collective unconscious and suffering of his people. He moved into a simple adobe house that he built with his own hands at the edge of the floating gardens in Xochimilco. Here, he had daily contact with the Indian people and their customs. Their simple ways influenced him greatly. He was outside the superficialities of the cultural and intellectual life of Mexico City.

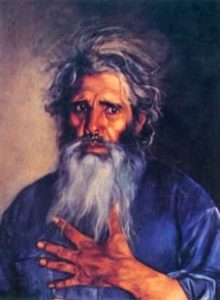

He painted Father Jesus in 1927, which is now in the National museum of Mexico City. It is generally considered one of his best paintings. It’s a moving painting of two women keeping vigil over a dead man. It is a graphic and powerful work. This painting earned him first prize at the First Inter-American Painting and Engraving contest thirty years later.

Acording to Anita Brenner in her book, Idols Behind Alters, Goitia had a mystical spirit and was intoxicated by his own emotions, very much like the painters of the Middle Ages, She wrote that he left to his people a record of his times filled with the sentiment of communion with mankind.

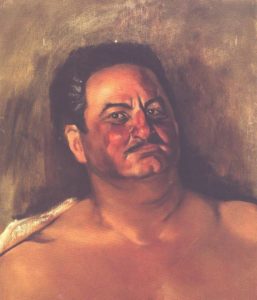

In truth, he was very complex. He was a tormented, deeply religious man given to fanaticism and anti-social behavior. Yet, he was deeply human and sensitive, and loved the village he chose to make his home. It’s this love and sensitivity that gives power to his paintings.

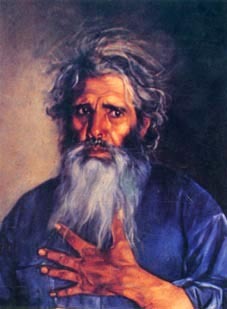

He had his own distinguishing technique. It was shadowy and archaic in appearance, which heightened the feeling of martyrdom in the people he portrayed. He painted scenes of the Revolution and the poor – beggars, wounded men, common people weighed down by their physical and moral misery. His work is filled with emotion imbued with humanity. It’s a strikingly personal interpretation of the misery, sorrow, and suffering of man, and its reality is mirrored in the reality of his own austere personal life.

Goitia’s life spanned the Porfirio DÍaz years, the Revolution, and the post-Revolution period. There is no question his times influenced his development both as a painter and a human being. He was a sensitive soul marked by the pathos of the human condition as he saw it around him. In 1989 a movie was made about his life. The biography explored his life and his internal struggles – the conflict between art and religious faith – and how they played out in his art. The movie is appropriately titled “A God for Himself”.

Francisco Goitia died in 1960 in his beloved Xochimilco. He was an eccentric and gifted painter who chose a life of extreme poverty among the indigenous peoples of a village he adopted as his own. His anti-social behavior may have dimmed some of the light that was shone on his contemporaries, but he is still remembered in the hearts of his countrymen, and that’s where it really mattered for Goitia. His sincerity and compassion are timeless, and he’s rediscovered with each generation. The government of Zacatecas organized a large exhibit of his work to celebrate the state’s 400th birthday, and he received the National Arts Award.