Don’t let the name fool you, Ivonne Kennedy is a genuine Oaxacan painter—but on her own terms.

Kennedy was born in 1971 in the city of Oaxaca. While ‘foreign’ last names are not terribly uncommon in Mexico, they are pretty rare in Oaxaca, and ‘foreign’ first names even more so.

So, quickly, before we get into her art, let’s dive briefly into her backstory. She is not related to the famous US Kennedys, but her Irish great-grandfather did migrate to the United States in the early 20th century. Her grandfather, James Cecil Kennedy, was a bit of a rebel who ran away from home when he was 15. He made his way to South America, working in mines in various countries, until he was caught sleeping (or drunk, depending on which family member you talk to) while guarding a mine. His punishment was to be sent to Oaxaca.

There he met the woman who would become Ivonne’s grandmother. Since then, her familial line is completely Oaxacan. But the family has kept ties with aunts, uncles and cousins in the United States, and two of Kennedy’s siblings eventually moved north. They have also kept their distinct familial heritage alive by continuing to use English given names.

But Ivonne is far more comfortable speaking in Spanish than in English.

Perhaps Ivonne inherited some of her grandfather’s rebelliousness. No one anywhere in her family is an artist, nor had any inclinations towards it. Chafing at “being trapped” in school, she informed her parents at age 16 that she was quitting. “I wanted to do something different.” she says.

What that was, she didn’t know. Art did not immediately come to mind. “I enjoyed drawing and painting like all children do,” she says, but she did not like her art classes, remembering the teachers being too critical. “I felt greatly frustrated because they would let me do anything…”

So, she studied English and helped her parents with their business for a time. This left her mornings free, so she just began doodling and other experimentation, beginning to see geometric shapes in everything.

That is when someone suggested that she take some art classes at a local Casa de Cultura (Cultural Center) which she did in 1987 and 1988. At first, she wasn’t so sure it was a good idea, given her bad experiences in educational institutions, but Francisco Verástegui, graphic art/painter and teacher at the center, encouraged her, giving her some quality drawing paper to take home.

Ivonne immediately went into books at her house to find something she wanted to draw, eventually settling on an image of a crab in a Time Life book on nature. She finds the choice curious to this day because Oaxaca’s famous Francisco Toledo painted images of crabs – and she had no idea who he was at the time.

Her experience at the Casa de Cultura was positive enough that she felt confident to approach the Rufino Tamayo Fine Arts Workshop, Oaxaca’s best-known art school, for further studies. From 1988 to 1990 she learned to work with oils, acrylics, ceramics, graphics and more, alongside some now-noted artists such as Virgilio Santaella, Manuel Cisneros and Tomás Pineda. The school also introduced her to other art-related endeavors such as curation and promotion, which have been instrumental in developing her career.

Curious about her family, she decided to live in the US from 1990 to 1993 in southern California. She continued to experiment with art, but at the time had young children, so much of this work was relegated to the evenings. In Pasadena, she sold her very first piece of art, a portrait commission for $100, which she immediately spent on art supplies.

But she found disappointment there as well. Rejected from a collective exhibition, and not understanding why, Kennedy decided she needed to know the art world and art market better, and not just produce quality work.

So, she returned to Oaxaca with this purpose, having only a faint inkling of the state’s role in international art. Along with learning the obvious, such as Oaxaca’s long art history and the fame of Francisco Toledo, she began asking many questions to many local artists about how they develop their work and promote it. “Many of them did not take me seriously and were even annoyed by my questions.” Others did not want to help her, despite the boom in Oaxacan art, because they had stable markets and did not want (more) competition.

Undeterred, she continued to learn what she could, both in artistic techniques and marketing. Most of her development has been through trial and error, but in 1996, she did study drawing with internationally-famous, Mexico City-based muralist Gilberto Aceves Navarro. Her work began to be included in some local exhibits and galleries, with her first solo show, La Mano Mágica, opening at the Galería de Arte de Oaxaca in Oaxaca city.

The most important lesson Kennedy has learned about art as a means of making a living is that you need to be entrepreneurial. She has exhibited in many galleries in Oaxaca, Mexico City and abroad, but much of that success has come through programs and organizations that she founded herself.

Her first, and most important, is the Guenda Group: the soul of things based in her home in the northern San Felipe neighborhood in Oaxaca city. She co-founded the group in 2003 as one of ten women looking to “[break] the inertia of the local gallery and museum scene,” that often worked against women. By banding and promoting together, Kennedy and the others have not only gotten their work shown more widely in Oaxaca, but also in the rest of Mexico as well as in Europe, the United States and Cuba. Today, the organization has over two dozen members involved in just about all branches of the visual arts. While the membership is still exclusively female, their work does not focus on feminine or feminist topics. They are more interested in showcasing the quality and diversity of work of their members.

In 2015, Kennedy founded the El Atanor ceramic workshop inviting both Mexican and foreign artists to collaborate and work. In 2020, she opened the Ivonne Kennedy Gallery and in 2021, the Central del Arte Project. The center of her world is a traditional rural home on the northern edge of the state capital, far from the artist scenes in places like Jalatlaco and Xochimilco closer to downtown. The location works for her not only because it is more spacious and peaceful, but also because her work focuses on collaborating with far-flung artists and institutions, so foot traffic is not a consideration.

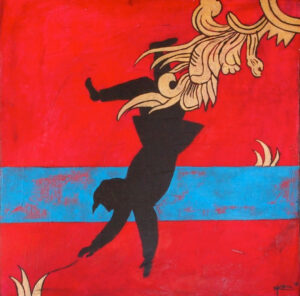

If the business end of her career is unconventional for Oaxaca, her artwork is even more so. Kennedy is absolutely an Oaxacan artist. Her use of strong colors testifies to it. But beyond that, she charts her own path.

Her early professional work focuses heavily on cityscapes. There is some influence from Aceves here as depictions of multiple buildings with their geometric forms are at least partially abstracted and repeated into patterns. Cityscapes generally take their cue from urban grays and muted colors, but Kennedy keeps her colors strong and clear. The two should clash, but she makes it work.

She might have just continued to make a living from such semi-abstract pieces, but since the early 2000s, her work has ranged from the realistic figurative to the completely abstract. Her focus sometimes changes abruptly and apparent in her shows. Emotionally, changes come “…so I [don’t] get bored with myself, as the works become formulaic.” Finding ways to stretch and break formulas that she devised herself is the basis for the shifts.

It also signals something of a rebelliousness with “Oaxacan art” or what people think of as Oaxacan art. Kennedy says that she became “almost depressed” with the Tamayo Workshop’s obsession with the human form and for many years, would not work with it again.

Oaxaca’s art has heavily focused on the figurative and folkloric, something that is not only nurtured by the rural and indigenous character of the state, but also the outsized influence of Francisco Toledo, who died only a few years ago. Kennedy acknowledges and appreciates this background: “Oaxaca is full of stories. We have legends and myths, customs and magical realism and strong colors.”

But she finds the work of most artists living here to be repetitive, reworking what someone else did many times. “If someone paints a crane, the next day a bunch of cranes appear from other studios, because there isn’t an honest search for inspiration. Artists are looking for acceptance and a place in the state’s art market.”

The other element is that she does not believe that she has a definitive style, nor should she be required to have one. “Life is too long to stick with just one way to express things.” But for marketing, she admits it makes things significantly harder. “The art market does not generally accept that an artist has various styles. It likes to be able to recognize an artist’s work on sight. Buyers can feel disappointed when they do not recognize work from an artist.” But she feels this is wrong- that it is far more important that an artist produces quality work, not that it has unifying features, as uniformity does not guarantee quality.

Her works have grappled with the use of the figurative and abstract, often in how they can go together. When she came back to the human form for a bit, she stretched out the lines for something of a Cubist result. She has had a long interest in alchemy and mysticism, and looks towards these for inspiration. It has resulted in many works with spheres, spirals and floral patterns as well as identifiable figures, often with an emphasis on perspective. More recent works have taken that to a more narrative bent, as she believes both the figurative and the abstract have roles to play in telling stories.

To do all this, she feels the need to separate herself, both physically and artistically, from “the Oaxaca art scene” to a more international one. “It is not easy. I do not have a formula and I do not know if an idea will work out on the canvas.”

But one thing that will remain steadfast is her tie to strong colors. “In Oaxaca, color is everywhere, in the clothes, in nature, in the buildings and even the food. You can say in Oaxaca we even eat color.”

Leigh Thelmadatter is a freelance writer whose first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published by Schiffer in 2019.