Part of the wonder and adventure of experiencing life in Ajijic, Mexico is the incredible diversity of color in the natural world — pungent reds, a range of blues, pale purples, brilliant yellows — and of form: broad leaves, lace-like foliage, sharp narrow leaves of bamboo, and fields of cultivated raspberries, set between surrounding mountains and the broad expanses of Lake Chapala. This magical lakeside fishing village has become home for several thousand North Americans and a vacation paradise for an equal number of visitors each year.

For those who love the arts, the lakeside has a growing art colony which includes both Mexican and North American artists who paint, sculpt and write about this land and inland sea where every turn reveals an ever unfolding array of possibilities.

Within this milieu, native artist Efren Gonzalez, friend and mentor to the many North American artists, has absorbed the natural beauty of this land and the residual spirit of the indigenous peoples who thrived along the lakeshore. From this internal core he creates paintings and sculptures that powerfully express both landscape and “human-scape” of this paradise. And — sensitive to the needs of his pueblo — he also serves as owner/director of the Efren Gonzalez Cultural Center, situated in the heart of Ajijic, where he paints, sculpts, and teaches painting to forty-five young people who study each afternoon after school.

Through the combined patronage of residents and visitors, and commissions from astute buyers, Efren supports his educational center and has the freedom to create a variety of works which integrate his creative vision with a deep understanding of Mexico’s pre-Columbian roots. He is also open to new ideas and approaches to art being brought in from the North.

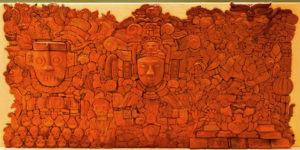

Efren’s creative talent was uniquely challenged in June of 2010 by a North American couple (who requested their names not be used) who visited his studio and asked him to create a three-dimensional mural incorporating materials and themes which spoke of both the natural world and the spiritual reality of Mexico. Thinking “sculpture,” Efren sent them to meet a friend of his who works in stone. However, within a few days the couple returned, insisting that Efren create the bas-relief mural for their home. He agreed. They settled on terracotta (fired clay) as the material to be used. This decision meant that Efren would have to develop the equipment and skills to work and fire clay so the three-dimensional parts (each piece limited to about 16″ in size) could then be assembled into a twelve-foot long by eight-foot high mural.

Working together with the aid of sketches, artist and patrons developed a relationship that reminded me of past great moments in art history when such synergistic liaisons enabled significant shifts in artistic understanding and vision. Efren, spiritually in tune with the historic arts of Mexico, was, like his predecessors, encouraged by patrons who wanted a work expressing not only their love of Mexico but also reflecting in a fundamental way the country’s spirituality and pre-Columbian roots. Efren, with support from his patrons, found just the right mix through the powerful visual rendering of spiritual themes and the use of terracotta, a pre-Columbian material. The completed mural is a pivotal work which has clear significance in the history of Mexican Art.

Brief history of patron-artist relationships

Until the late nineteenth century when art began to be marketed as a commodity, commissions that embodied the possibility for synergistic unions spurred significant changes in the direction of the art of many cultures. For example, Rembrandt (1606-1669) was commissioned by the Shooting Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq to do a painting known as “Night Watch” (photo #4 Rembrandt’s Night Watch) now located in the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam. Guild members, who were hired to teach young wealthy men to shoot the newly-developed muskets, were willing to allow Rembrandt to break the mold of the traditional (posed) group picture and to place their eighteen members in a dynamic crowd scene where the Captain and his Lieutenant are shown leading a crowd forward. This creative change in an art form, made possible by both the artistic genius of Rembrandt and the openness of his patrons, enabled a significant step forward in the history of art.

When Pope Julius ll commissioned the genius Michelangelo (1475-1564) to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he gave the artist the freedom to interpret God’s creation of humanity. Again, the give-and-take relationship between the Pope and Michelangelo allowed the artist the freedom to depart from traditional form in which all holy figures were idealized and often adorned with halos. The result was a living work, not filtered by conventions, with real flesh-and-blood humans in a direct relationship with a living God.

In 1814, Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) was commissioned by the Provisional Government of Spain at the end of the French occupation to paint the French execution of innocent civilians on May 3, 1808. Again, the need of the patron to reveal the vicious acts of the French under Napoleon gave the artist journalistic and artistic license to create a work that broke traditional rules in which the victors in war were honored. Goya’s bold refusal to show the faces of the French executioners stole their power to intimidate, while making them abstract instruments of death. Then, bringing all of his creative genius to bear, Goya placed the entire emphasis on the terror felt by the Spanish peasants about to be killed. This creative move made his painting “The Third of May, 1808” a universal anti-war and anti-violence statement that remains viable today.

As in the examples of Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Goya, and Picasso, Efren’s sculpture in terracotta, encouraged by North American patrons, revived the lost (or long misplaced) art of terracotta bas-relief while integrating a creative understanding of the spiritual brought to life with bold colors and forms that remind the viewer of the best in pre-Columbian art. In the finished plastic work, a rendition of human tranquility nurtured by good and threatened by evil, Efren created a synergy between medium, vision, and symbolic cues, which pulls the viewer deep into Mexican history. Using the earth, fired into clay then painted, the finished mural compels the viewer to consider the fundamental question of how good and evil interact in human life.

The artist explained to me his intent for each of the elements within the mural:

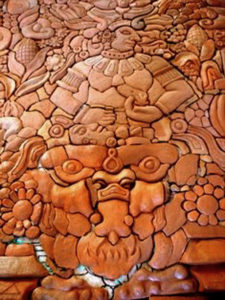

“The face of the infinity figure in the central panel is tranquil. The use of purple paint indicates the figure’s peaceful state while the universal infinity symbol and the lotus flowers in each hand further confirms the figure’s pacific role. The four essential elements surround this unifying figure with fire on the left lapping up around the persona of evil, above the air is filled with birds, fertile earth lies to the right supporting growing corn, and nurturing water, filled with turtles and fish, flows across the bottom.

On the left panel of the terracotta mural, a figure holding a decapitated human head is seated on a pyramid of skulls, and surrounded by roaring flames, images which make clear the dark role of evil in human life. The skeleton lurking at the bottom further confirms evils role in all violent acts.

The right panel depicts an indigenous woman nursing a child with her right breast and feeding a corn plant with her left. Flourishing corn plants, symbols of life and renewal, grow on each side of a throne centered on top of a pre-Columbian stone pyramid. This pyramid balances the skull pyramid in the left panel. The jaguar head under the throne marks the woman’s “royal birth.”

Most interesting is the complexity of line and forms. The entire mural is filled, confirming that nature abhors a vacuum. The movement and curving lines remind the viewer of the lush natural setting around Lake Chapala. As with much of pre-Columbian art, every space is filled. Diego Rivera, following the ancients’ lead, filled his murals until images were piled atop forms which sat atop symbols. This very Mexican composition and vision is distinctly different from the more rational images created in Europe and North America. For example, the irregular shape of the mural at the top, right, and left sides, coupled with the use of curved lines and forms within the work, create a strong sense of earlier organic works by Classical Maya artists. The overall composition, with the inclusion of pre-Columbian elements, pulls the viewer into a time and place nestled at the heart of Mexican culture and art.

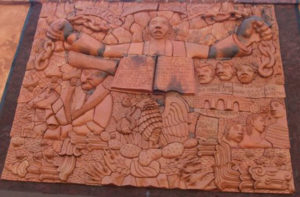

Having successfully completed and installed the terracotta mural in his patrons’ home, Efren decided to experiment with terracotta in relief for his entry in the prestigious Ajijic mural contest “Pinta tu Fachada” to celebrate Mexican history and independence. This second terracotta mural, a more figurative work, has the same power to draw the viewer into the mural. Here, Efren’s intent was to honor the heroes of the battles for independence from Spain and those of the Mexican revolution. The finished work was recently installed on the wall of the school just in front of the parochial church in central Ajijic.

Efren describes his work as a reflection on both the fight with Spain for independence and the Mexican revolution.

“Hidalgo is the central figure, and on the right side is the revolutionary leader Emilano Zapata. The left side includes local heroes from the state of Jalisco: Marcos Castellanos, a priest who lived for a time in Ajijic and who died fighting the Spanish; Jose Santono, also killed by the Spanish; and Encarnacion Rosas from Mezcala. The Puente Calderon (bridge), where Hidalgo lost an important battle, was included because of its location in Jalisco.

The open book in the center represents both a text about the struggle for independence and a text about the revolution. The broken chain symbolizes freedom, the cactus, and the eagle are symbols from Mexican history. The terracotta is exposed to remind the viewer of Mexico’s pre-Columbian history and our connection with the earth.”

Given the innovative nature of the work, it was no surprise that Efren won the contest whose $30,000 peso prize will be paid when he finishes a similar bas-relief mural for the city hall in Chapala. Efren is now working on this third terracotta mural.

When Efren and I talked about his winning this contest, his response reveals a great deal about the quality of this man who has dedicated his life to art and to his pueblo (home town and people).

“I thought I had a chance, but I didn’t want to get my hopes up, so in the end it was a surprise. I am thankful my work won because the money will enable me to do more with the school for the children. I had already learned a great deal from finishing the first mural. The work itself was very satisfying. Whether I won or lost did not matter. The important thing was the Mexican Independence — this inspired me to do something different. I wanted Hidalgo to be prominent. Now, I am excited that my winning will focus attention on our independence and will require me to do a third ceramic (terracotta) low-relief mural for the city building in Chapala.”

Efren’s use of clay to mold these three-dimensional works revives an ancient tradition. Terracotta (fired clay) dates back to the discovery of fire when humanity realized that clay became water-resistant when placed in a fire. The hotter the fire, the more resistant the resulting terracotta was. Clay’s pliability enabled artist to mold pots used to cook food and store liquids, and to make sculptured votive objects intended to insure the fertility of people, animals, and the earth itself. Many of these tiny offerings, ritually thrown into the Lake Chapala by ancient indigenous inhabitants, were found when the lake receded several years ago.

The historical works most relevant and inspirational for Efren are the early examples of terracotta art from many pre-Columbian civilizations in Mexico. The artisans and architects at Comalcalco, an ancient Maya site located in Tabasco near the mouth of the Usumacinta River, worked primarily in fired clay bricks for the structures and terracotta panels to adorn the facades. Other Maya sites on the Pacific coast of Mexico also have remarkable examples of fired clay panels and incensarios.

The new terracotta bas-reliefs by Efren Gonzalez evoke the natural beauty of the lakefront, a soul connection with ancient art forms and the history of a land, and a creative collaboration between artist and patron that allows freedom for new interpretations of what the past can mean to us all.