When Marianne Ferrucci first learned that her husband was seriously ill from a mysterious viral infection, she went out on the second floor balcony of their house in northern Mexico, gazed up at the sky and the mountains, and said aloud to herself, “It is very important to stay in touch with the eternal.” She sat there quietly watching the sunset and gathering her strength. The sight of the open fields and the distant mountains had always given her the strength to go on.

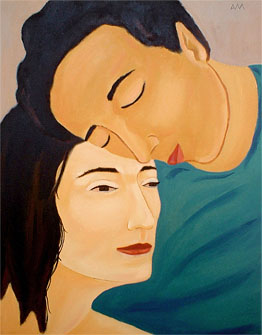

painting by Anthony Maulucci

Back in the house she went looking for Richard and found him asleep on the living room sofa. She couldn’t resist the urge to cover his naked legs with the brightly-colored quilt they had bought from a local weaver. She looked at him as he slept, his squarish face with its heavy brows and deep-set eyes always made her think of the bust of a Roman senator she had seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was dressed in his usual denim shirt and khaki shorts. The colorful quilt over his legs suddenly reminded her of the extraordinary experience they’d had in their first year in Mexico. They’d visited Las Pozas, an unfinished rain forest sculpture garden built by the eccentric millionaire Edward James, and had gone swimming in the natural blue-green pools and when Richard came out of the water he was instantly dressed in a robe of crimson butterflies.

Marianne had married her husband when he was a struggling artist living the bohemian life in New York’s Greenwich Village in the late 1960s. Richard Ferrucci had grown up in a well-to-do family in Greenwich, Connecticut, and they had often said that moving from Greenwich to Greenwich Village was a major step upwards on the stairway of cosmic consciousness. The life of a young, attractive bohemian couple was exciting — they went to all-night parties, drank tequila, used some recreational drugs on occasion, experimented with other sexual partners, and made passionate love together whenever the mood took possession of them, which was at least twice a day. They were described so often as a beautiful couple that the sobriquet stuck, and they became known by the label of The Beautiful Couple, or its diminutive, the BC. Then Marianne got pregnant and life took a serious turn. In a rare moment of solemnity, she made a statement of principles: with no uncertainty, she told Richard she was determined to have the baby. She wanted to get married, and they must leave New York because she refused to raise a child in an “atmosphere of depravity,” as she put it. She expected Richard to desert her for his freedom and his decadent lifestyle. Surprisingly, he told her he was in love and would happily give up his old life for her and the baby if she would agree to move to Mexico. Why Mexico, she had asked. Because, he told her, it’s cheaper, it’s warmer, and it’s real. So they formulated a plan and shocked all their friends by “going bourgeois,” working hard, saving money, and staying home at night. Feeling betrayed, their friends avoided them. But the Beautiful Couple didn’t mind. They had each other and they were happy. Everything was going so well, and then tragedy struck. About three months into her pregnancy and a month before they were scheduled to leave for Mexico, Marianne had a miscarriage. This hit them hard and nearly capsized their little family boat that had been sailing along so smoothly. Marianne was plunged into depression. She quit her job, never went out, and hardly ate for three weeks. Richard was at his wit’s end and feared the worst, that Marianne would put an end to it all with an overdose of her sleeping pills. Then one morning Marianne rose up like Lazarus, cast off her gloom, and declared that they must move to Mexico and start a new life as planned, just the two of them. New York had taken their baby, she went on, but she wouldn’t let it destroy their love. And so they went to Mexico.

That was thirty-five years ago. And they had so completely embraced their new life that they had long ago ceased to think of themselves as Americans.

Richard’s growing reputation as an up-and-coming naturalistic painter had made it possible for him to sell pieces in New York through some of their old friends. Within three years of their arrival, when they were sure they wanted to stay in Mexico, they managed to scrape together enough money to buy a small house that was a near ruin and, with a lot of hard work, had transformed it into what it was now, a very comfortable, very spacious light-filled hybrid of the pueblo and mission style stucco house.

The exterior of the house was all blue, like Frida Kahlo’s childhood home, and so they called it La Casa Azul. It had a white double front door: you opened it, walked through a short hallway and stepped from under an arch into a sky-filled courtyard surrounded by six doorways opening into four rooms, the living room, kitchen, dining room, and library. On the other side of the courtyard there was another archway leading you to the slightly sloping backyard with a terrace, a garden, and some scattered fruit trees. The second floor also had four rooms, three bedrooms and Richard’s studio. And there were two balconies, one on the inside overlooking the courtyard and another on the outside, commanding a view of the open fields and distant mountains, where Marianne had sat and thought about eternity.

When Richard learned he was dying, he told Marianne that after he was gone he wanted her to return to New York so that, as he expressed it, she would be in a better position to see that his work got the attention and treatment it deserved. He was not afraid of dying, he assured her, but he was terrified that his work would fall into oblivion. “You need to be there in New York to make sure that doesn’t happen.” She couldn’t refuse him because she believed he was a great artist whose work deserved the recognition that had eluded him so far and also because he had been willing to leave New York to start a new life with her and their unborn child. His willingness to make such a sacrifice for her thirty-five years ago obligated her to make a sacrifice for him now. She owed him. The only hurdle in the plan was that she didn’t want to leave Mexico.

But now that the Beautiful Couple had decided that Marianne would return to the U.S., the most pressing question was what to do about Casa Azul. It was for both of them a work of art and selling it to just anyone was unthinkable. It would be equivalent to putting their children up for sale on the open market, if they had had any children. But the marriage had remained childless. They had tried often enough after the shock of their first loss had abated, but Marianne had never managed to get herself pregnant a second time. “It just wasn’t meant to be,” she often said to console herself. And now she could see the wisdom of that omission from their life. With all of his driving ambition to be a great painter, Richard would have made a poor father. And with all the demands placed upon her by her husband’s needs, she would probably have been a neglectful mother, and that would have caused her much anguish.

painting by Anthony Maulucci

However, another woman’s children came to fill this gap in their life. They had a housekeeper named Marta, a local woman whose husband had been killed trying to cross the border into the U.S. Marta had two girls, Vianca and Corazon, who were now sixteen and fourteen respectively. Their mother had been the Beautiful Couple’s loyal friend and housekeeper for twelve years and the BC had grown very attached to these girls, especially Marianne, and she was as reluctant to leave them as she was to sell her house to strangers.

Both of these sisters had an adolescent crush on Richard, one openly, the other in secret. Now that he was dying, their lives revolved around him, and they did everything they could think of to make him happy and comfortable. They cooked his favorite meals, they read him stories, they brought him tunas, the succulent cactus fruit encased in a prickled dark purple husk that had to be opened very carefully and expertly. And they posed for him as he sat up in bed. He was often too weak to get up, but he could still manage to paint from a sitting position. “I’m becoming more like Frida Kahlo every day,” he would comment with playful irony. “Just look at my eyebrows. They’re growing together.” And the girls would laugh excitedly.

At first, Marianne was delighted by the devotion of these two sisters, but she came to resent it since they were to some extent usurping her place, although they seemed so innocent and charming that it was difficult to be overtly angry with them. So she called them “The Silly Sisters” in what appeared to be good natured teasing but which had a barely perceptible malice just below the surface. She kept on calling them “my darlings” and kissed them as warmly as ever. Nevertheless, she seethed beneath her poised and still-beautiful exterior.

That she had aged well and was still beautiful was a source of enormous secret pride for her. And now more than ever, being in her mid-fifties though she looked ten years younger, she felt obligated to conduct herself with dignity. That was one of the qualities she loved so much about the Mexican people — not only did even the poorest of them carry themselves with simple dignity, they respected it in others. They expected it in others, particularly those who in their eyes, like the Beautiful Couple, were great successes and superior individuals. And Marianne had always aspired to meet the expectations that people had of her.

It was Richard’s opinion that she tried too hard and cared too much what people thought of her.

“Why give a hoot what people think? The opinion of the mob doesn’t matter a damn,” he often counseled her.

And her usual rejoinder was, “We’re not talking about the faceless mob. These are specific individuals, people we know, and that makes all the difference in the world.”

“Perhaps. But only if their opinion carries any weight,” he would reply, needing to drive his point home and have the last word.

Needing to have the very last word was one of Richard’s habits that had begun to grate harshly on her nerves just before they found out how sick he was. After that, all the little annoyances endemic to any marriage seemed petty and mean-spirited.

Unlike most men, Richard was almost always ready to talk about his feelings. Marianne was grateful for this. After getting sick, however, he became less demonstrative on that subject. She remembered the night they came home after hearing the bad news from the specialist in San Antonio. Even though they had been traveling for many hours and were exhausted, they had to unwind before going to bed. They sat up in their beloved library and drank brandy out of big snifters the way they used to at a quiet hotel bar after a raucous party in some artist’s loft in SoHo. (These snifters, in fact, had been smuggled out of the Pierre by a “pregnant” Richard.) Richard had hoisted his snifter towards the walls lined with books as if he was about to make them a toast. “All this literature that I’ve spent so much time reading and not one of these damn novels can teach me how to die.”

“How about Tolstoy’s Ivan Illych?” Marianne had suggested.

“Not even that since I’m not about to go through a religious conversion, and I have no Gerasim to comfort me.”

“You have Vianca and Corazon.”

“True. But I should have put the time into reading philosophy instead.”

“You read what you liked, and what inspired your work. It was for pleasure mostly, not an education.”

“Perhaps I have lived too much for my own pleasure.” He paused in thought. “What was it Montaigne said? Something about the best philosophy can do is prepare us for death?”

“Yes, I think that’s what he said.”

“Well, here I am on the threshold and I’m not prepared.”

They lapsed into silence. Richard drank down the rest of his brandy and stared at Marianne with glittering eyes. “Do you know how beautiful you are? God, I never truly realized it till this moment. The nearness of death has sharpened my already heightened perceptions. But I just never comprehended, and I’m not sure I do now,” he went on, warming to the subject. “Never let myself take it in completely because I think that would have been too much for me, too much wattage in my weakly incandescent brain, it would have burned right through me and left me in ashes. But I can see it now, and it can go right through me and kill me because I’m almost there anyway. Just need one big jolt to finish me off.”

“Please don’t talk that way! You’re being morbid and we’ve got to stay positive. There’s always hope. We can see some doctors in New York. We can get some help from the Mayo Clinic. We can try visualization and the naturopathic approach. There are many things we can do.”

“Sounds like a desperate grasping at straws.” After a pause to collect his thoughts, Richard said, “First of all, I’m not going back to New York because I don’t want our old friends and enemies to see me this way. Especially our enemies. I want them to remember us as we were then, as the Beautiful Couple. And secondly, I’m dying, I know I’m dying, and I want to die right here in this house where I’ve been so happy. Now don’t start crying. Don’t go to pieces on me, Marianne, because now more than ever I need you to be strong. I need to count on that rock-solid inner mountain of yours to see me through to the end. I need your incredible radiant beauty to get me over the last hurdle into the beyond. And thirdly…” Marianne was sobbing at this point, “thirdly… now you’ve made me forget. Oh yes, and thirdly, I’m dying from some weird viral thing and there’s nothing those goddam New Wave freaks can do about it! Let’s face up to it. There’s no mumbo jumbo that’s gonna rescue me from this one….”

But Marianne hadn’t heard his third point because she was crying too hard. And she didn’t hear what he said next, that he didn’t need philosophy because he had the example of his grandfather and his father, who had shown him what it meant to die with dignity.

About a week later, as they were having lunch on the terrace, Marianne voiced a question that had been troubling her since that night in the library.

“You say you don’t want to see our old friends in New York because you want them to remember us as we were then, but it’s okay for me to…” she hesitated, unable to finish her sentence, but her husband understood her perfectly.

Richard put down his fork and wiped his lips with is napkin before speaking. “I know it seems hypocritical, but it’s not… You haven’t changed. What I mean is that you’re still beautiful, as beautiful as you were then. Maybe more so. And you’ll have my paintings of you. They’ve captured your beauty and made it timeless.”

What a high opinion he’s always had of himself, she thought. Marianne smiled with self irony. “Thank you for the compliment, Richard, but I’m not so sure everyone shares your feelings.”

“Of course they do. They don’t say it but I can see it in their eyes. Just think of the way they worship you around here.”

“I think ‘worship’ is too strong a word. Don’t exaggerate.”

“I’m not exaggerating in the least. You know I’m not.”

In truth, Richard’s nude paintings of Marianne had caused quite a stir when they were first exhibited in Mexico City ten years ago, and the exhibit became so notorious that it traveled across the border to San Antonio, Dallas, and San Diego, garnering mostly glowing reviews everywhere it went. With her blonde hair, blue eyes and creamy complexion, Marianne had always stood out in their adopted country, but now that Richard’s paintings had made her into a celebrity the local people looked upon her as a kind of goddess.

She had trembled with fear at the thought of playing the part of the goddess. She wanted to simply break apart and be a simpering foolish woman of whom absolutely nothing was expected. Why couldn’t she be weak and dependent and have someone else take over her role as the beautiful wife of the famous painter? She didn’t feel like a mountain of strength. Hardly! She felt rather like the sacrifice in some ancient pagan ritual. And she was afraid she would fail to live up to Richard’s expectations. She would cringe and whimper like a terrified animal in the end. Death was not something she knew how to deal with. Did anyone? She began to resent the fact that Richard had such unrealistic expectations of her. Why didn’t he have enough inner strength of his own? What did she have that could be transferred to him, how could she help him during his final transition from life to a state of non-existence? How could anyone help another human soul through this final passage? And what about her needs? Who would help her find the wisdom and strength to be his handmaid in this preparation for the end?

The more she dwelt on these thoughts, the more furious she became. These and many more questions were buzzing in her brain like a swarm of angry wasps. What right did he have to ask her to go to New York when he knew she loved living in Mexico? The slower pace and their relatively stress-free lifestyle suited her perfectly. The last thing she wanted at this time in her life was to be thrown back into the maelstrom of the New York art world with all its jealousies, ruthless competition, and over-inflated egos.

When she sat on the balcony at various times of the day and looked out at the mountains and up at the sky, the wasps in her head became still and one idea sang out clearly with the purity of something angelic. Her love for Richard was greater than her love for herself, and when he was gone she would have nothing but her memories and her devotion to his work. She knew she must be content with that, and she accepted it with a peaceful heart. Somehow it will work out, she repeated to herself.

But then, later that same day or the next, she would look at Richard lying on the terrace with one or both of the sisters attending to him, and she would feel a hot stab of hatred pierce her heart. Why was he doing this to her? Why wouldn’t he try to find a cure for his affliction? Why was he leaving her to fend for herself, why was her breaking up the Beautiful Couple? How could he be so mean and selfish as to go and die on her when they were in the prime of life? She would be left alone with nothing. No children, just paintings that she would have to sell to collectors and museums. She chafed at the thought of having to pay court to these vain and powerful people. Who would want her? No one. It would be the paintings and the details of her intimate life with Richard that would be sought after. Everyone would want to know her, not for herself, but for what she had been transformed into by Richard’s paintings.

Perhaps not even Richard knew her and loved her for what she was inside, but rather what he imagined she was, what his imagination had made of her on canvas. Was this her destiny, to be loved and admired for what she represented and never for herself? If so then beauty was indeed a curse, although she hated thinking in such clichés. She thought of Jane Morris, William Morris’ wife and the model for some of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s greatest paintings. She too was a beautiful woman who had become a symbol for something that could not be expressed in words and was only half-understood. Would she share the same cruel fate? She was a flesh and blood woman, and she wanted to be loved as a real woman and not worshipped as a goddess.

Summer had passed into fall and Richard had grown worse. He was weaker and now seemed very close to the end. Every night after Marianne had meditated and done her best to clear her mind of all resentments, all negative thinking, she lay in bed and held him as he went to sleep, praying in her own way for his recovery or for his passing, if it must come, to be peaceful. She listened to his breathing, half-expecting each breath to be his last, as she went to sleep. And she often woke in the middle of the night from strange dreams, full of fear, anxiously listening for the normal rhythm of his breath.

As she was returning from a walk one afternoon in late September and listening to the wind in the willow trees, she saw Corazon running towards down the sloping yard and her heart leapt with fear, then flooded with guilt. Richard was gone, and she had not been with him in his final moments.

“Señora!” the girl called excitedly. “Señor Richard is sitting up and asking for you. Come quickly!”

Marianne stared uncomprehendingly at Corazon’s radiant face, then dashed up the slope and across the terrace into the house. Richard was indeed sitting up in bed, his face pale, the hairline across his forehead darkened with sweat. He was smiling at Vianca as Marianne came breathlessly into the room. Richard’s gaze turned to her and his eyes lit up. “Amor,” he said.

Marianne took his hand and kissed him tenderly on the lips. “How do you feel, Richard? Any better?”

“A little. The fever’s gone and I’m stronger.”

“That’s wonderful!”

“Yes, but I know it’s only temporary. What’s this?” he asked, looking at the white stone Marianne had placed in his hand.

“Isn’t it beautiful? So pure. I found it while I was out walking. See the shape of a heart?”

“Yes, I see that,” said Richard rubbing the smooth stone between his thumb and forefinger. “Thank you, darling. I’ll treasure it for as long as I can,” he said as he placed the stone on the bedside table.

“Perhaps it will bring you good luck, Señor Richard.”

“It might. You never know.”

Marianne remarked that it was a good sign that he was looking better.

“My last hurrah. Let’s make the most of it.”

Marianne chose to ignore this cynical comment. “Will you have some dinner, Richard?”

“I believe I will, yes. But that’s not what I had in mind. Vianca knows what I want right now, don’t you dear?”

Vianca blushed. “Yes, Señor Richard. I will find Corazon and we will get dinner started,” she said as she turned and left the room.

“It’s shameless how much she adores you,” said Marianne. “She’d do anything for you. They both would.”

“It’s harmless, and I’ve never taken advantage of their feelings for me. At least I don’t have that on my conscience.”

“Fine, but do you have to allow her to be so open about it, especially in front of me?”

“Isn’t it better that way?” He gave a slight shrug. “Anyway, that’s how she is — open and honest. It’s a rare gift.”

“I’m not sure I can share your enthusiasm.”

“Never mind all that. Lie down with me for a bit.”

Marianne stretched out next to him on top of the bedspread, saying she was too dirty from her walk to get underneath with him.

“Fine, just get over here,” and Richard pulled her close and kissed her, his hand going automatically to her neck and breasts. She felt his overpowering desire for her and she quickly undressed. “Lock the door,” Richard whispered, and she scurried naked to the door and back again. Richard had his pajamas off and the covers thrown back. His penis was erect and quivering slightly. Marianne got on top of him, spread her legs, and inserted his hard penis into her. And so they made love tenderly, without the overwhelming passion of their youth or the enduring passion of what had still been their greatest joy until Richard was stricken, but nevertheless with a sensual purity and a deep pleasure.

“Even though I’m an atheist, I have always been grateful to the power that gave me you and our love,” Richard said when they were lying side by side.

“Do you remember that time you were covered with butterflies when you came out of the pool?”

“At Las Pozas, yes, how could I forget?”

“Well, I’ve never told you how it made me feel because I never really understood it until now.”

“Go on.”

original painting by Anthony Maulucci

“It’s hard for me to put this into words. Please bear with me.” Marianne paused to arrange the sentences in her mind the way she always did when she had something important to say. Richard watched her face, saw the blue-green of her eyes deepen like the pools he recalled diving into at Las Pozas, saw the way the setting sun reflected in the dresser mirror struck her profile, etching it against the rose-colored wall, and he felt his heart would stop. “You looked like the god Pan,” Marianne continued,” a faun or some other mythological creature and I laughed with delight when I saw you, but I also trembled with the knowledge that I would never truly have you all to myself. Not ever. You belonged to nature, to the great Earth Mother, to the creative force that had claimed you as an artist long before I came into your life. And at best all I would be to you was a partner who would do whatever it took to keep you going because she was so madly in love with you.”

After a long pause Richard said, “You were always more than that, mi amor. You were my muse. Yes, you kept me going, but not in the sense you mean. Not as an assistant who takes care of the practical matters of life, although I’ve always appreciated your doing all that. But as an inspiration who got me through the darkest hours when I thought my talent was negligible and my work was shit.”

Marianne was too moved to speak and so she remained silent.

After a time, Richard said, “Perhaps that’s where I picked up this weird virus.”

“Could it have remained dormant for thirty-five years?”

“Why not? Anything’s possible.”

They lay together and held each other without speaking for a while longer until one of the girls knocked on the door and announced that dinner was ready.

Later that night as they were getting ready for bed, Marianne said, “Speaking of the practical matters of life, what are we going to do about this house?”

“I was just thinking about that,” Richard replied, “and I believe I’ve found the perfect solution.” He paused, his face beaming. “We should give it to Marta.”

“I admit she’s been a good housekeeper, but give it to her?”

“Well, maybe not give it to her, but let her live here with Vianca and Corazon as legal tenants, caretakers… whatever. That way we’d know the house was in good hands and you could come back for visits whenever you wanted.”

“It’s something to consider very carefully.”

“And my ashes could rest here,” Richard continued. “I know it’s not something you want to think about, but I would like my ashes to be placed in a special spot on the property. I haven’t decided exactly where yet, but it’s either going to be near the willow trees or at the bottom of the slope….”

But Marianne was weeping silently and didn’t hear the rest of what Richard told her.

As it turned out, that was the last time the Beautiful Couple made love. Richard got increasingly worse and died a few weeks later of a heart attack brought on by the viral infection. It happened in his sleep, and Marianne’s one consolation later on was the thought that he had died quickly and painlessly. At first she was stunned and expressed no emotion when she woke up early that morning and discovered that he was dead. She wandered through the house and around the backyard in a benumbed state of shock. But when the sisters arrived a few hours later and she told them what had happened, she broke down, and their outburst of tears brought on her own and the three of them wept and held each other in the kitchen as the sun came up.

Now that the dreaded inevitable had happened, Marianne was caught up at once in a swirl of practical considerations. Dozens of decisions needed to be made. She had always been remarkably steady in a crisis, and somehow, in spite of her grief, she was able to meet the demands made on her by this, the greatest crisis she had ever had to deal with.

Arrangements for the cremation and the memorial service had to be made. Families and friends had to be notified. Calls from newspapers preparing obituaries had to be answered. Hundreds of details needing attention grasped her like so many tentacles. The worst moment of all came when she took a call from the dean of the biology department at the University of Texas in San Antonio thinking it was someone else. The dean asked her if she would consider donating her husband’s body to their Center for Viral Research. She listened in a growing panic, choking up so much that she was unable to spit out the profanity that had risen acridly to the back of her tongue, and slammed down the receiver.

When it was all over, when the tsunami of attention had passed, when the families and old friends from New York had all left and she was finally alone, Marianne’s true grief began. For two weeks after Richard’s death, Marianne had been swept along on this terrible tidal wave of extreme emotion that to her seemed to strike a false note as something artificial and staged. She went through it all in a dream state, as if it someone else were performing all her actions. She had felt detached from all the open grieving and eulogizing and commiserating as though she had been watching events unfold from the director’s chair behind the camera. She had been denied the quiet time she needed to mourn his passing and rejoice in the remembrance of Richard’s creative spirit and the sacredness of their love.

When the time was right, she told the sisters and their mother about the Beautiful Couple’s decision to make them the permanent residents of La Casa Azul. The gift was accepted in the solemn spirit with which it was offered, as a sacred trust in the honor of Richard’s memory and their wonderful life together.

Marianne could now focus her energy on the preparations for packing her few belongings and Richard’s many paintings and drawings for the move to Manhattan where she would begin her new life as the caretaker of Richard Ferrucci’s legacy. Richard’s family, their old friends, the art dealers who had contacted her — everyone expected this of her, and she had come to believe that there was no escape from the part she must play. From struggling painter’s wife to the famous artist’s widow, her role in life had always been defined by her relationship with this extraordinary man who had been her most loyal friend, closest companion, and greatest lover. And it had been this way for so long that she no longer knew who she was apart from him and his work.

Everything was at last ready on a crisp bright morning towards the end of October. The sky was a fierce blue. The gentle wind in the willow trees stirred her soul as she stood for the last time at Richard’s little shrine, a tiny pyramid made from white stones. She looked up at the mountains, then picked up the jar with crimson paint and a brush and painted two butterflies on the largest white stone in the center of the shrine. When she had finished she stood up and, looking reverently at the image, said, “Good-bye for now, Richard.”