A Balloon in Cactus

© United States Postal Service, 2009

In 1934 during the depths of the Great Depression, horse trainer Tom Smith was living out of a stall at Mexico’s Agua Caliente racetrack in Tijuana. Flat broke, Smith shared the stall with Noble Threewit, who trained horses for a friend of Charles Howard. Howard was seeking a trainer for his new horse, Seabiscuit, a seemingly incorrigible Thoroughbred. Seabiscuit looked and behaved “like a train wreck.” If not for the innate horse-whispering talent of trainer Smith, it’s doubtful Seabiscuit would have become a cultural icon, let alone have his image on a U.S. stamp.

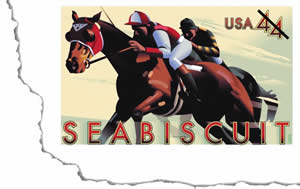

On May 11th, a 44-cent stamp featuring Seabiscuit, will be issued by the U.S. Postal Service. It’s significant because we the people did it! It took eight long, frustrating years, but we did it. People think they don’t have power in Washington but, when there are enough of us, we can do anything.

When Laura Hillenbrand’s bestseller, Seabiscuit: An American Legend, was published, millions of readers were inspired by the true story of “an undersized, crooked-legged racehorse named Seabiscuit,” who beat all odds and became a pop-culture phenomenon. In the 1930s, as many spectators attended his races as today attend the Super Bowl. Those who couldn’t squeeze into the track hung off lampposts, stood atop their cars, and climbed onto roofs just to catch a glimpse of him.

When U.S. President Obama appeared on the Tonight Show on March 19, ratings soared higher than they’d been in years, with 20 million viewers, but when Seabiscuit raced, 40 million people listened on their radios, including President Roosevelt.

Impassioned by the book, I toured Seabiscuit’s home, Ridgewood Ranch, and spoke with another tourist. Over time and telephone, we became friends and discussed the possibility of attempting to get Seabiscuit on a U.S. stamp.

Fat chance, right? We had no money, no lobbyists, and no Washington connections. We had only passion, and a belief that “No” meant, “Try harder.”

We started a grassroots movement beginning with local book clubs, then book clubs nationwide. Their members not only signed our petition to the Committee, they circulated it to all their friends, who sent it to everyone they knew. We put the petition on the Internet, we trolled the streets for signatures, promoted the idea on TV sports shows, wrote articles for small newspapers and big ones like the legendary Chicago Tribune, haunted racetracks for more signatures, and returned to Ridgewood for attendees’ signatures at the premiere of the movie, “Seabiscuit.” We did everything we could think of and when we ran out of ideas, we thought up more.

Thousands of people volunteered: an Arkansas soybean farmer, a Louisiana pharmacist, a Kentucky woman who canned hams for Hormel, a Massachusetts landscape designer, racetrack people, book lovers everywhere, and ordinary folks from all walks of life.

Despite discouragement, disillusionment, and distress, we wouldn’t give up. Seabiscuit never quit when faced with insurmountable odds, so we wouldn’t quit either. His fierce determination to win had inspired Americans in the throes of the Great Depression, and today, his stamp will be issued during the worst economic crisis since then.

When you see the Seabiscuit stamp, remember that people can do anything and, if Tom Smith hadn’t been living out of that Agua Caliente horse stall, we probably wouldn’t even have the stamp.