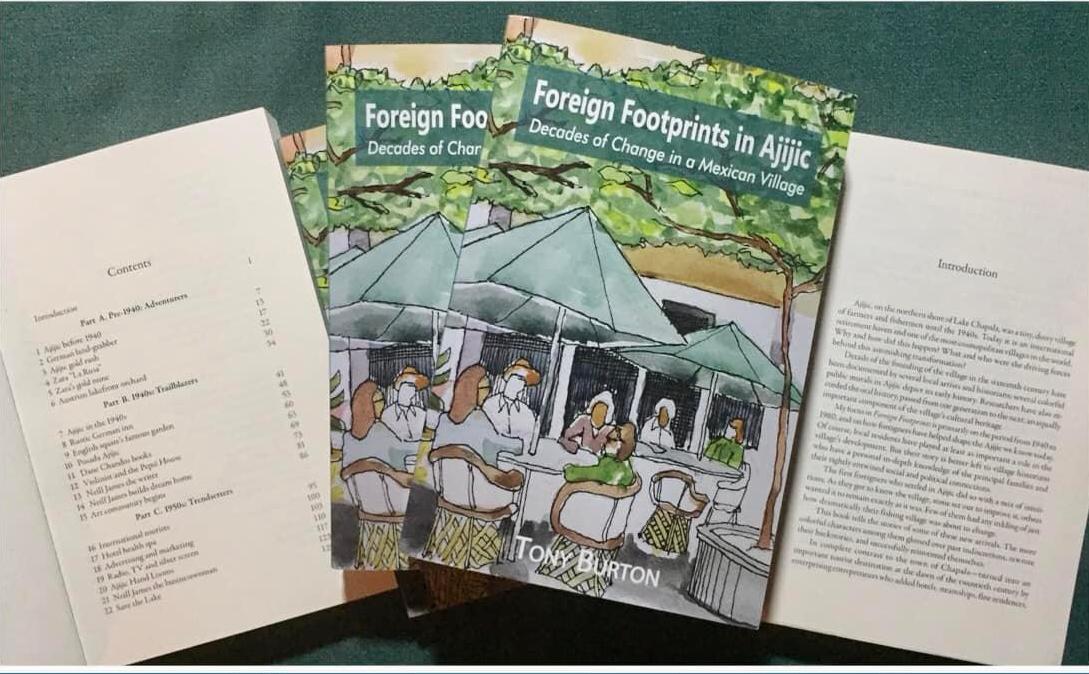

Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village

Tony Burton. Sombrero Books, 2022.

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback / Kindle

Tony Burton’s most recent book, Foreign Footprints in Ajijic, captures a period of time in Ajijic’s history from the 1940s to the 1980s that is both intriguing and eye-opening. It is hard to imagine the comings and goings that took place in this seemingly quiet fishing village nestled beside Lake Chapala, a stone’s throw from the bigger and more accessible village of Chapala.

Tony Burton’s most recent book, Foreign Footprints in Ajijic, captures a period of time in Ajijic’s history from the 1940s to the 1980s that is both intriguing and eye-opening. It is hard to imagine the comings and goings that took place in this seemingly quiet fishing village nestled beside Lake Chapala, a stone’s throw from the bigger and more accessible village of Chapala.

But hidden inside this gentle, easygoing community are tales of crime, passion, greed, generosity and flowering creativity. Each of these stories left a mark on the evolution of the village. The book is a portrait of a fascinating foreign community that lived full and intense lives against the background of its laid-back host.

Foreigners came to the lake area for many reasons—some seeking adventure, others as guests of friends, and still others to seek their fortune. And, though it may have been a temporary venture, many stayed on or returned for the same reasons that drew me to this jewel of a village—the special light that makes the flowers scintillate and changes the color of the mountain from a subtle palette of mauve to deep purple, depending on the time of day. Added to its visual beauty was the agreeable climate due to its sizeable lake, once the heart around which the village thrived.

Ajijic for most of its existence was a small village of fishermen and farmers that sustained itself through a strong sense of community and family. It was too remote and inaccessible for the general Mexican population to give it much thought as a holiday escape. Most goods were delivered by boat, as a road came very late to the area and there were no comfortable inns or hotels to lure outsiders. Those who came from abroad and stayed were rugged individualists and adventurers or people redefining themselves with newly minted pasts of dubious truth.

Some seeds of change were planted in the twenties when screenwriter Charles Kaufman lived in Ajijic for a few months. How he discovered this remote village is hard to say. But he passed his enthusiasm on to a friend, Louis Stephens, who acquired property in Ajijic and offered its use to Helen Kirtland, a new arrival to the village who developed a weaving industry that was instrumental in creating a new destiny for the community.

Russian dancers and Paramahansa Yogananda

I was amazed to read that the guru Paramahansa Yogananda passed through in 1929 to visit the Russian dancer Zara (La Rusa) and her partner Holger, whose lives in Ajijic were so infamous that even I knew their story though I came much later to Ajijic. The arrival of Yogananda cleared up a mystery for me.

I lived in Mexico City during the sixties and taught at a girls’ bilingual high school. I was asked if I would be their gym teacher, a program of movement they were to do several times a week. And, to my surprise, I was asked to give them a yoga class in the style of Yogananda, a method I had to learn very quickly, or I should say, I learned along with my students. The surprising thing was that I had never heard of yoga being taught in an American high school. And I wondered where the head of the school got the idea. I had barely heard of yoga being taught at all back then.

From Burton’s book, I now understand that this influential man had passed through Mexico, and astonishingly, through the tiny village of Ajijic. The threads of connection in our lives are like a giant spider web with odd threads that connect our lives to others in unexpected ways. To this day, over fifty years later, I still do his method of yoga though it’s unlikely my body will be unnaturally preserved after my death as it is said his was.

Burton’s book delves into a bit of earlier history, mostly to set the groundwork for what’s to come in the forties. A surprise for me when reading of this pre-growth period was how many German and British nationals with a small scattering of other Europeans had arrived and ventured into business in Ajijic before it was actually discovered by adventurers from the North American continent. It’s a wonder how they knew of this tiny enclave from so far away, and why they felt a need to develop or exploit or be a part of it before the United States or Canada ever discovered its potential.

Once we get into the forties, more creative types start to settle in the area. One of the first was La Rusa, whom I mentioned earlier, an eccentric ballet dancer who reinvented herself many times over, and lived an audacious and extravagant life that was never questioned nor maligned by the local people. She and her Danish partner settled in Ajijic for life and devoted much of their time to the gold mines they had laid claim to. I hadn’t realized before reading Burton’s book, though I lived seven years in Ajijic, that Rancho del Oro’s name was due to a literal truth. At one time Ajijic was rich in gold and silver, and many foreigners came to try their hand at staking a claim.

The Posada Ajijic and Neill James

Aside from giving the history of how Rancho del Oro came to be established, Burton tells how many other areas came to be named and developed. For anyone living in one of these places, it would be an especially interesting read. This is also true of how the waterfront came to be developed as well as how other parts of the area. For instance, the old Posada Inn has a long and fascinating history. In reading about it, I wondered why I hadn’t been curious about it before. When I revisit Ajijic, as I will soon, I will have a completely new perspective of this old inn full of so much fascinating history.

Another place I hadn’t given much thought to when I lived there was the Neill James’ house where so much of the ex-pat life takes place. Yet, here again is a fascinating story of a remarkable woman. Neill James was a woman of extraordinary independence and courage as were so many women who settled and contributed to the area. Each one is worthy of a book.

But I will focus on Neill James as her mark is everywhere in the identity of what Ajijic is today. Neill James was a writer, an entrepreneur, and a property developer with a deep commitment to the Mexican community. She was a visionary who did a lot to mold what is the best of the ex-pat community. And the bequeathing of her property to the community after her death has done a lot to bring in people and anchor foreign residents to the village. Many have followed her example of giving back to the people who have welcomed them onto their land.

Ajijic for artists and authors

One of the things that intrigued me when I moved to Ajijic was the proliferation of artists in what was then a relatively small and remote village. Galleries flourished and the art scene was vibrant.

In reading Burton’s book, I learned how integrated the arts were, even far back into its past. Many artists came and left but used Ajijic as inspiration for some of their work. I found it hard to leave the village without bringing back some of the more recent art work being done, and have a huge linocut by Pat Apt and a small painting by Juan Navarro, both artists mentioned in Burton’s book. I also have a wonderful poster by photographer Xill Fessenden. So though I’ve left, I’ve taken some of the energy of the area with me.

Though I focus on the physical art scene, all the arts found a home in Ajijic. I hadn’t realized how many writers, cinematographers, dancers and musicians passed through—each with an interesting story and background. And though I wondered how the Little Theatre found its way into this community, I had no way of satisfying my curiosity. Thanks to Burton’s research, I no longer find its existence in this small Mexican village an anomaly.

Foreign Footprints in Ajijic is packed with information, and yet it’s an incredibly easy read. The book is thoughtfully organized into five sections: Pre-1940: Adventurers, 1940s Trailblazers, 1950s Trendsetters, 1960s Free Spirits, and 1970s Modernizers. Each fascinating chapter is no more than seven or eight pages with some chapters even shorter. One can pick it up and browse anywhere for an immediate answer related to one’s particular interest. I think of it as a Wikipedia for anyone interested in the area. The research done on the book is extensive—over thirty pages of notes at the back of the book and four pages of bibliography. For the readers’ convenience, there’s a chronology of key dates.

Although I read Foreign Footprints in Ajijic from cover to cover, there’s so much there that I’ll be targeting particular interests of mine when I bring the book with me on my next visit to Ajijic.

For anyone living or visiting the area, to read Burton’s book can only enrich the experience.

***

Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village is available at Diane Pearl’s in Riberas; Hotel Villa QQ in Chapala; at La Nueva Posada and Mi México in Ajijic; and via Amazon (both print and Kindle editions).

I recently read this book and as a resident of Ajijic, I would like to inquire about some of the information. It was a challenging read. I would like to receive more details about certain statements and would like those to be confirmed by the author. Some of my friends grew up here and are mentioned in the book or their family members. RE Foreign Footprints in Ajijic.

Thanks so much. Please, reply by message or email.

Hello Johanna, Responding via email, TB.