Jews have lived in Mexico since the fourteenth century. In 1492, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain ordered the conversion or exile of all Muslim and Jewish subjects. Jews who had converted to Catholicism were called New Christians, or Conversos. Also known as marranos, they often continued practicing Judaism in secret after they had officially converted.

Historians believe Hernán Cortes had converted Jews among his men when he conquered the Aztecs in 1521. In 1531, a group of Spanish Jews and Conversos who had originally found refuge in Portugal, emigrated to Mexico, then called Nueva España, under the rule of Royal Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza. In the New World, they believed they could retain their historical Spanish identity and continue to practice Judaism. Because Mendoza was a common name among Spanish Jews, some historians suggest the Viceroy himself had a Jewish or Converso background.

Until 1571, those who had immigrated to the New World were able to practice Judaism openly. But that year marked the beginning of the Mexican Inquisition, an extension of the one in Spain. Again, both practicing Jews and Conversos lived in fear. During the Spanish Inquisition, thousands had been burned as heretics. The Mexican Inquisition was not as bitterly hostile as the Spanish. Records indicate that fewer than one hundred were denounced as heretics and executed by burning.

Kingdom of Nuevo León

In 1579, King Philip II of Spain established the Kingdom of Nuevo León (present day Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and South Texas), a colony north of Nueva España to be governed by Luis de Carvajal, a Portuguese/Spanish nobleman born in 1539 to Jewish converts. To help populate the colony, both Conversos and practicing Jews were welcomed. Caravajal was later accused by the Inquisition of heresy and died in prison. Monterrey still bears some of the customs of his Jewish heritage, particularly the regional specialty of cabrito (roast goat, based on the Jewish cuisine of the founders of the city) and some Sephardic family names like Garza.

But within sixty years, according to historical evidence, the descendants of the original settlers moved to what is now New Mexico, Arizona, and California, then still part of Mexico, bringing with them vestiges of Judaism which survive to this day.

Discovering our Jewish Roots

One family, named Villarreal, freely acknowledge their remote Jewish ancestors and have written about them from the point of view of the Conversos. The family, with branches in South Texas and Mexico, make it clear that they will remain Catholics.

Another example is that of Father William Sanchez of Alberquerque. As a boy, he never understood why his Catholic family spun tops on Christmas, shunned pork, and spoke quietly about ancestors who left Medieval Spain. After watching a genealogical television program, Father Sanchez tracked his DNA and discovered that he and his family were part of New Mexico’s crypto-Jews, descendants who maintain some Jewish traditions of their ancestors while adhering to Catholicism. Today about 20,000 Mexicans are able to trace their Jewish ancestors.

Two genealogical studies of the eighteenth century, the Archivo General de la Nacion de Mexico and the Ramo de la Inquisition, suggest that Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the father of Mexican Independence, had a Converso background and that Bartolome de las Casas, a Bishop who fought to free slaves in Nueva España, also had Jewish ancestors. Although their families were sincere converts it is ironic that expelling the Jews from Spain precipitated events that eventually led to Spain’s loss of Mexico.

Between 1700 and 1865, some adventurous Jews immigrated to Mexico to escape the grinding poverty and anti-Jewish attitudes of life in the Old World. While they were not allowed to become citizens, a right granted only to Catholics, many who came during the one hundred sixty-five years many carried housewares, clothing and novelties to remote villages of Mexico on the backs of burros or mules, similar to those who traveled to the West of the United States.

In 1865, Emperor Maximilian I issued an edict of religious tolerance and invited a number of German Jews to settle in Mexico. Few accepted the emperor’s invitation, because two years later, an official count listed only twenty Jewish families in Mexico City although there were probably more in the rest of the country.

Separation of Church and State

After Maximillian was executed by firing squad in 1867, Benito Juarez became the president of Mexico. His liberal rule enforced the separation of Church and State. Non-Catholics were allowed to establish themselves in Mexico. In 1882, after the assassination of the Tzar Alexander II, a significant number of practicing Jews from Russia entered the country.

In the early years of the twentieth century, large numbers of Jews arrived after World War I. Some were fleeing pogroms of Russia and Eastern Europe. These were Ashkenazic Jews, descendants of medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine and associated with northern Europe and Germany.

Another group, descendants from Jewish communities in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal), were called Sephardic, from sephardit which means “Spanish” in modern Hebrew. They fled the collapsing Ottoman Empire, which included Turkey and Morocco. Because most of the Sephardic Jews had retained their Spanish heritage, they spoke a dialect of Spanish called Ladino, which made their lives easier than their Ashkenazic counterparts.

All immigrants faced economically difficult lives, and Jews faced the same financial problems as all Mexicans. But coming from a part of the world where their lives were hard, they had no difficulty in adapting to conditions in Mexican villages. Mexican Catholics and Jews shared an important common characteristic. In both groups, the family was the predominant social group.

Why did Jews choose Mexico as a destination rather than the United States? Mexico was attractive to them. Many had relatives or friends already who had settled in the country. And in 1921 and 1924, United States enacted laws restricting immigration.

From 1920 to 1930, Jews in Mexico enjoyed a period of stability during which they prospered.

The only recorded incidents of anti-Semitism came in the 1930s, when neo-Nazi right wingers, financed from Berlin, staged anti-Jewish demonstrations in Mexico City. The demonstrators gained little support from the Mexican people. During the 1930s, the Jewish community battled anti-Semitism by forming the Federación de Sociedades Judías, as well as the still active Comité de Central Israelita de México.

The 21st Century

Mexico today has a Jewish community of between 40,000 to 50,000 with about 37,000 living in Mexico city. The majority of them, Mexican citizens who practice Judaism, are descendents of people who, from 1881 to 1939, found refuge here. Because Mexican economic prosperity allowed religious tolerance, Jews enjoyed the same rights as any other Mexican citizen.

Most Mexican Jews are considered middle to upper-middle class. Even with the recent economic troubles facing Mexico and the Jewish community, this country has attracted Jews from other countries in Latin America.

In Mexico City, there are more than twenty synagogues, several Kosher restaurants and at least twelve religious schools where almost 80 percent of the Jewish youth receive their education. Jewish communities can also be found in Guadalajara , Monterrey, Tijuana, Cancun and San Miguel. Throughout all of Mexico, 95 percent of Jewish families belong to a synagogue. Mexico City also contains the Tuvia Maizel Museum, dedicated to the history of Mexican Jewry and to the Holocaust.

In early March, 2000, Pope John Paul II called anti-Semitism “a massive sin against humanity” and the Holocaust “an indelible stain on the history of the last century.” In June, 2003, President Vicente Fox helped pass a law that forbids discrimination, including anti-Semitism, putting into the law what has been practiced for years.

Jews have served in positions in the Federal Government. From 2000 to 2004, Jorge Casteñada Gutman was Foreign Minister. From 2000 to 2005, Santiago Levy Algazi was director of the Social Security Institute. Others are prominent members of the Chambers of Commerce in Monterrey, Guadalajara, and Tijuana, whose former president of the City Council was Marcus Levy. David Saul Gaukil, a member of the Tijuana City Council, said, “No one [has ever] commented adversely that I am Jewish.” Although Tijuana has a population of 2,000,000 its Jewish population is only about 2,000. Tijuana also has the Congregacion Hebrea de Baja California, made up almost entirely of converted Mexican Catholics. Its non-ordained leader, Carlos Samuel Salas, conducts spiritual outreach to Mexicans of Jewish ancestry.

Jews and descendents of Jews in Mexico have been well-respected journalists and artists. Jacobo Zabludovsky became a much-honored Mexican journalist and the first anchorman in Mexican television with his program 24 Horas. Frida Kahlo, was the daughter of Guillermo Kahlo, born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in Germany after his parents moved there from Hungary. Emigrating to Mexico in 1891, he changed his name to Guillermo. The lover of Leon Trotsky and flamboyant artist maintained that her father was a Hungarian Jew and never denied her Jewish heritage. In 1935, her husband, Converso descendant muralist Diego Rivera, wrote, “Jewishness is the dominant element in my life. From this has come my sympathy with the downtrodden masses which motivates all my work.” Many other prominent Mexicans, like Presidents Porfirio Diaz, Francisco Madero and Jose Lopez Portillo, have referenced their Jewish descent from Converso roots.

There was even a Jewish bullfighter, Sidney Franklin, born Sidney Frumkin in New York in 1903, who fought bulls in Spain and Mexico. Hemingway, in Death in the Afternoon, wrote “Franklin is brave with a cold, serene and intelligent valor.” He died in 1976, after a career fighting bulls and presenting bullfights on American TV.

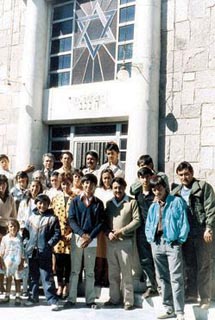

Chapala and Ajijic

The Chapala/Ajijic area is home to a group of ex-pat American Jews who have their own synagogue, The Lake Chapala Jewish Congregation, in Riberas del Pilar, which offers services twice each month on Saturday mornings and twice each month on Friday evenings. For most of my adult life I have been a member of a synagogue. I appreciate the fact that there is a vibrant Jewish community here and I have continued to have the opportunity to participate in religious services. Occasionally The Lake Chapala Jewish Congregation interacts with our Mexican Jewish counterparts in Guadalajara. We also interact with the Mexican community here in fulfillment of the religious requirement to perform mitzvot, to honor the commandments and do good deeds. The congregation also has Mexican members who have returned to their ancient Jewish roots.

The majority of Jews in the Chapala/Ajijic area are retirees from the United States, like me, or from Canada, seeking the more relaxed Mexican life-style as well as the lower cost of living. Although the Lake Chapala Jewish Congregation currently has no permanent rabbi, there are several members whose knowledge and background fulfill the role very well, enabling them to lead services. As in the past, Jews find they have much in common with their fellow Mexicans. Both groups are sincerely religious and family oriented. And historically, both have been victims of oppression and tyranny.

The combination of perseverance of Jews and tolerance by Mexicans, both official and as individuals, has permitted Judaism to put down deep roots. Ultimately, however, like all of us who live in Mexico, our future will depend on Mexico’s social and economic progress.

The Mexican records grossly underestimate the number of Jews who died as the Catholic Church would certainly have an incentive to do. My father Daniel Rios was still a practicing Jew who came from a endogamous line of Crypto Jews with deep roots in Monterrey.

Thank you for this most interesting information. I did my DNA and discovered we were part Jew from the Nuevo Leon area of Mexico. I had no idea we had this history in our family and have been delighted to find this treasure.

Glad the article was helpful to you! Please recommend MexConnect to your friends.

The entire description is somewhat accurate however, as a true Sephardi Jew I can tell you that the first wave of deportations of Jewish people came in the year 1438, the second one came in the year 1462 and the third and biggest deportation was in July of 1492. No moslems were expelled from La España, which was around 200,000 Jewish people. From minor laboring jobs to the right hand man of

Ferdinand and Isabella. Luis de Carabajal y Cueva, a Spanish conquistador and converso was the first Jewish person to land in what is now known as an upper Texas. The first Jewish person settled in Brazil in 1654 via his parents being from Holland. Which was one of the few countries who accepted us. Mexico has had indeed Jewish people for a long time but, NEVER since 1492, furthermore, those who called themselves Jewish aren’t since their lineage from the mother side it isn’t. Many conversations have happened in Mexico.

Thank you for taking the time to post this interesting and informative comment. The mistaken reference to “fourteenth century” has been corrected. Thanks for helping to improve MexConnect!