You might say that it all began on an ordinary day in New York – the treasure hunt, that is. My 23 year old daughter Elise was just back from Spain where she had been teaching English to grade school students. One quiet evening, as we sat together at home, I showed her four large photographs of artworks painted by my grandfather, the artist Ettore Serbaroli (1881-1951). She noticed that two were ceiling paintings, while the others were wall murals. On closer examination, her eagle eyes noticed that the ceiling paintings were signed and dated 1913. “Those must have been done by grandfather when he was in Mexico just before the revolution,” I told her.

“Any idea where they are now?” she asked.

“Nope,” I replied, “but I sure would like to know.”

“Me too,” she said. And so the quest began.

Several weeks later we were on a flight to Chihuahua with no clues to go on but four old brown photographs. Not much, I’ll admit, but we were hopeful. Situated about 900 miles north of Mexico City and only about 240 miles south of El Paso, Texas, the city of Chihuahua is a delightful place to look for treasure in September. Our hotel, paid for through frequent traveler points, was neat and clean and within walking distance from the center of town. The next morning, after a good night’s sleep, a tasty Mexican breakfast, and a brisk walk to the central plaza, we were ready to start the hunt.

In the small, but bustling city hall across from the Plaza de Armas, we asked a number of people where we could find information about artworks that were done in Chihuahua from 1909 to 1913. A few seemed perplexed and simply re-directed us to other people and places. After a long walk from the plaza, we found the bureau of records where the employees were all very friendly, but not able to provide us with much information. Across the street was the large impressive mansion named Quinta Gameros, but we found none of Serbaroli’s artworks there; and we ended our first day tired, empty handed and still full of hope that we would stumble onto something that would make our trip worthwhile.

The next day, we were up early and walking once again to city hall, but decided first to visit the magnificent 18th century cathedral known as El Sagrario, located in the center of town on the Plaza de Armas. Inside, with the scent of incense all around, I whispered to Elise how her great grandparents had their one-month-old daughter Judith baptized there in the midst of a bloody revolution.

© Joseph Serbaroli, 2009

After our visit to the magnificent cathedral, we walked the streets and took in some of the sights and sounds of a place that is vastly different from Mexico City. At the end of the city’s major thoroughfares we could observe either the Cerro Grande or the Cerro Coronel, two of the small mountains that sprout up prominently from the city’s flat topography like the rounded crowns of great sombreros. Even if we were not able to find what we set out for, the opportunity to amble along the boulevards to see what our grandparents saw, and to be in the place where they lived, was a real treat.

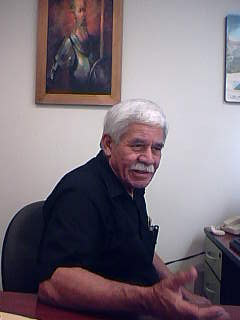

Our second visit to city hall gave us our first really good lead. We were informed that Chihuahua had a cronista or historian named Señor Ruben Beltrán who had an office in a modern building that was not too distant. Although daylight was quickly waning, we decided to try our luck but, when we reached the office, we were informed that he wouldn’t be back until tomorrow. Not a problem. There were a number of good restaurants in town, and we now had plenty of time to find a cozy one where we could savor the Mexican cuisine and plan our next day’s agenda.

© Joseph Serbaroli, 2009

When we showed up the next morning, Señor Beltrán was very cordial. At first, he sensed that we were like other Americans who visited the city on a genealogical search of their ancestors. When we explained that we were searching for art treasures, he perked up. He is a sculptor and he holds a special place in his heart for the art and artists of his city.

I began to relate the story of Ettore Serbaroli in English, while Elise translated into Spanish. Serbaroli trained in Rome at San Michele where he won the gold medal of honor, and later collaborated with the great fresco master Cesare Maccari to decorate the cupola of the world famous Basilica of Loreto. He immigrated to Mexico in 1907 and worked on the interior decorations of the Palacio de las Bellas Artes.

Two years later, he was brought from Mexico City to Chihuahua at the request of Governor Enrique Creel for an historic meeting between U.S. President William Howard Taft and Mexican President Porfirio Diaz in October 1909. In those days, it was highly unusual for an American President to travel outside the country, and Theodore Roosevelt’s visit to Panama the previous year was the first time any U.S. president had traveled abroad while still in office. The 28 year old Serbaroli was put in charge of designing and directing Chihuahua’s decorations for the grand occasion.

Later, during the revolution in 1913, he fled to San Francisco where he painted murals, then worked on Hearst Castle in San Simeon, and ultimately ended up in Los Angeles where he worked for the Hollywood studios painting portraits of stars like Bette Davis, Tyrone Power, Hedy Lamarr, Shirley Temple and others. Señor Beltrán was fascinated, and then we brought out the old, fragile photographs.

He carefully examined each one. The wall murals, he said, may have been in the Governor’s palace, but that burned in the 1940s and the interior was completely redone with modern ones. Unfortunately, there was no photographic record of the originals. The ceiling murals, he told us, may have been for either the Theater of Heroes or for the city’s main hotel; but the theater burned, and the hotel was torn down.

The kindly Señor Beltrán could see that we were disappointed. Had we come all this way just to find out that all the artworks were lost? He asked us to meet him the next day to visit a few landmarks where he knew there were murals. Although we had failed in our attempts to find the artworks in the photos, we held renewed hopes that we would discover some trace of our grandfather’s elusive paintings.

The next day, we visited a couple of mansions including Quinta Luz, Pancho Villa’s headquarters during the revolution, which houses the bullet ridden car in which he was assassinated in 1923. Two frescoes adorned the walls, simple landscapes, and I informed our guide that they lacked the touch of a well-trained Italian painter, who studied with some of Europe’s great masters. As my daughter translated my words, I mentioned to Señor Beltrán that my grandparents first met when my grandfather was working for Luis Terrazas, the wealthiest man in northern Mexico with an estimated 17 million acres of land. Our host said, “that’s where we’re going next. I set up an appointment with the caretaker of the Terrazas’ estate of Quinta Carolina.”

We drove about 20 minutes to the outskirts of town, and there before us lay the great summer hacienda of Quinta Carolina, Chihuahua’s equivalent of a palace. It once boasted a crystal dome that was destroyed in the 1970s by vandals. The property was now in shambles, but next to it was a church that was spared the same fate, and was still in use for the locals on Sundays. The caretaker called a young man, who came over to unlock the large carved wooden doors which were chained together through holes that once held stately brass door handles.

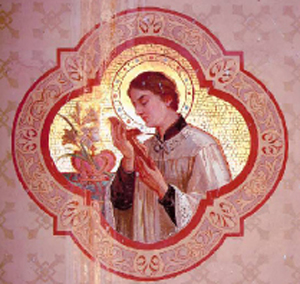

When he pulled open the massive doors, we glimpsed into a cool, dark interior that was a refuge from the blazing sun. Walking in, our eyes adjusted to the shade, and we were flabbergasted at what we observed. Around us was a masterpiece of art. As we strolled slowly up the center aisle, we saw portraits of the archangels painted on the left wall. On the right were portraits of the saints. At the front of the church, we were struck by the massive mural about 22 feet wide and 15 feet high that dominated the interior of the church. It had suffered from years of exposure to heat, humidity and leaks in the roof. Some of the color had faded, but it was otherwise intact. The design of the work was divided into two parts by an impressive altar, carved from white Carrara marble and signed by the Italian sculptor Adolfo Ponzanelli in 1909.

The mural depicts a seminal episode in the life of St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584) the bishop of Milan, for whom the church was named. It tells the story of the horrible pandemic that hit Milan and other towns in Europe in 1576. The plague did not discriminate. It struck old and young, rich and poor alike. On the left, grieving the loss of their loved ones, are the affluent families, people of nobility, who are saddened and helpless in the face of the disease. In spite of their wealth, there is nothing they could do but appeal to Saint Charles, their bishop, to help them. Saint Charles stands prominently on the right amidst the sick and the dying, who lie stricken on the front steps of the cathedral. Charles came from a wealthy family, but devoted himself completely to serving the people. Clothed in red vestments, he pleads with God to save them. The mural clearly demonstrated the young artist’s capability to provide a finely detailed, emotionally charged narrative in a single picture using only his paints, brushes and his creative thought.

My daughter turned to me. “Do you think that’s grandfather’s work?” she asked.

“It sure looks like it,” I replied. We walked over to the right side of the massive artwork where a signature is often found, but there was nothing.

Then the young man who had opened the church called to us in Spanish and said, “I think there is a signature over here.” On the left side, in large bold letters that were made to look from a distance like a design, was this inscription, “E. SERBAROLI 1910.” My daughter and I looked at each other in amazement, and with beaming smiles threw our arms around each other. It was a Eureka moment. We found something that was grander than our wildest expectations, something that nobody in our family knew existed. Señor Beltrán could hardly believe it either. Here was a man who had spent his life in Chihuahua and never seen the inside of this church, never knew the secret that it held or the masterpieces that were hidden away within it.

Back at his office, he hurriedly called the local television station and arranged for an interview at the church two days later, which was ultimately televised nationally in Mexico. On camera, Señor Beltrán marveled at the find, and gave a concise overview of the artist’s background and years spent in Chihuahua. During the interview, as Elise translated, I asked that the city government step up to save this hidden gem. The story was soon featured in the city’s newspapers. Within a few months time, the city council declared Quinta Carolina to be an historic landmark and has since budgeted 15 million pesos to restore and rescue this jewel as part of their cultural heritage.

As for Elise and me, we could not have been more pleased with our discovery and with the attention we were able to generate for a remarkable artist and his work. What began on an ordinary day in New York had turned into a week of adventure. And the treasure for us was not so much in the art that we found there, but in the experience of finding it during an unforgettable journey to northern Mexico.

Hi there. I’ve recently discovered my Mexican heritage.

Luis Terrazzas is my great great grandfather.

I’ve read you have visited his home.

I sure would love any insights and photos if you’d be so kind.

Robyn DelReal

Hi Robyn, thanks for your note. There is a lot of information in the public domain (including pictures) about your great grandfather. He was a wonderful man. If you would like to know more about him, I would suggest that you visit Chihuahua, where the local people are very helpful and hospitable. Kind regards, Joseph Serbaroli

Wonderful story , my search also lead me to your story , I want to find the early 1900 district of casonas that as I was told are now destroyed , my grandmother lived in that area with her affluent aunt and I believe her best friend was from an affluent Arab family , my grandmother passed away and I am starting from scratch