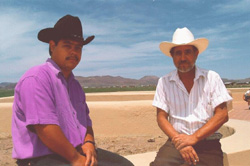

“When I walked into the museum and saw my ceramic sitting there beside the plaque for the Galardón, I was astonished. I had had no idea I had been awarded the Grand Prize.” José Quezada sat with his father, Nicolás, on the observation platform/roof of the Museum of the Northern Cultures in Nuevo Casas Grandes. He looked out over the restored ruins of Paquimé (the northernmost Pre-Columbian cultural center in Mexico, dating back about 1000 years) and shook his head.

The 26-year old was still finding it difficult to realize that he had just won Best-of-Show and over $800 US in the second regional competition for Mata Ortíz-style pottery sponsored by several state and federal governmental groups.

For José, he had come a long way in the ten years since his father had sat him down for some counseling.

Nicolás Quezada, 50 this year, is a younger brother of Juan, the artist who first taught himself to make earthenware in the style of the long-dead Paquimé culture 30 years ago. A few years later, Nicolás quit working as a railroad laborer to “test my luck with the pottery.” He learned by watching his brother and, over the years, has emerged as a master potter in his own right. Major US museums have collected his work and aficionados clamor for his pieces.

His son, José, was born in 1972, the same year Nicolás began making pottery. After graduating from elementary school, the boy followed in the footsteps of most of his friends. He did not continue his education, preferring to spend his time hanging out with his pals and occasionally working in the orchards and fields of the nearby Mormon community, Colónia Juarez. Prospects were bleak.

When José turned 16, Nicolás decided it was time for a fatherly chat. Placing his arm over José’s shoulder, he said, ” Mi hijo, what are you going to do with the rest of your life? Are you going to scrape by, working in the fields like your friends? Or, are you going to make something of yourself?”

Nicolás likes to begin work – making or painting his large pots – in the cool darkness of the early morning. The next day at dawn, José stepped into the cramped studio, sat down and began to really watch his father work for the first time. Within a week he was making his own pottery.

I first met him a year later. The young man was turning out small oval whitewares painted with simple red and black designs and leaving plenty of untouched negative space. Unremarkable pieces at first glance, but worthy of purchase when one realized the artisan had been practicing his craft for only a year.

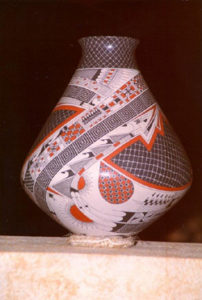

He continued to improve exponentially, following his father’s style of ” movimiento“. The theory is that a pot, or olla, is round. The painted lines shouldn’t contradict the form of the pot; they should curve from the rim or neck diagonally around the pot. His decoration became more complex and he filled his surfaces with the delicate red and black designs indicative of the modern Mata Ortíz pottery. This sweeping style was a dramatic break from the horizontal banded design of the ancient Paquimé ware. First employed by Juan Quezada, it is considered the giant leap that helped place the Mata Ortíz ceramics on the international art scene.

One day, Juan walked into the studio and found his brother admiring a beautiful six-inch high whiteware that had just been fired. ” Que bueno!” he said. “A fine olla you’ve painted.”

Nicolás smiled proudly. “I didn’t make it. José did.” Juan’s eyes shot up in surprise. The student had equaled the ability of his teacher. But, José’s technical talent was becoming worrisome for Nicolás. If Juan couldn’t tell the difference between the work of the father and the son, then who could? Time for more family advice, and this time I was there.

José innocently wandered into the studio later in the day and saw us still admiring the perfect pot. “You can’t keep doing them just like this,” his father told him. Nicolás went on to explain that José needed to develop his own style and not just continue to paint variations on his father’s themes. I added my own two cents’ worth. “This is the time to experiment. You’re still living at home. Even if you make something that is ugly and no one buys it – no big deal. Your mom will still put beans on the table for you, José. Three years from now, you will have a wife and kid and experimenting will be more of a risk.”

The next afternoon, I walked into the studio and was greeted by a smiling José who showed me three new pots he had made that day. An animal effigy figure, a canteen shape and a square pot were all drying on the workbench. All new, all experimental.

A trader began sponsoring him, purchasing everything José made over a six-month period. This encouragement bolstered the young man’s confidence and he continued to flourish. His pots got bigger and better.

Now, José is married and does have a kid – a little girl with Bambi eyes. They live with his wife’s grandparents in Mata Ortíz. Like many other potters in the village, he retrogressed for a while, but has rebounded with the big win in a competition of almost 300 ceramics, sponsored by FONART, the government folk art marketing arm and the Instituto de Antropología e História (INAH), as well as the Chihuahuan ministry of tourism.

And that day, José sat with his father and mentor on top of the museum and on top of the world. He had won the grand prize.