Arts of Mexico

COLONIAL PERIOD

The influence of Mexican design on Christian work has been the subject of much controversy. Bernard Bevan in the “History of Spanish Architecture” claimed that the influence of Mexican designs was practically negligible in Mexico and whatever seemed that way was due to “poor Indian workmanship”.

In fact, although the wonderful geometric textile designs and superb figures of the indigenous people were not directly applied to the Christian structures, the spirit and symbolism that gave rise to the ancient work is on the Christian structures. Much of the symbolism was done surreptitiously and had nothing to do with poor Indian craftsmanship.

Persistence of native themes continued even in the face of persuasive acculturating forces. The humanized sun and moon, fruit and vegetables unknown at the time in Europe, and the Indian faces and figures were not mere mistakes. From the beginning Indian influence was visible, especially in the handling of materials.

The Indian and Spanish traditions often over-lapped and reinforced each other. In Spanish architecture, sculpture and painting were used as architectural adjuncts – a relationship that had existed among the indigenous long before the coming of the Spaniards. Frescoes, used for ornamentation of church interiors throughout the 15th and 16th century by the Spaniards, coincided with the surface patterning that was characteristic of the different Indian cultures. It was a fortuitous coincidence that Hispanic inclination towards overall patterning and the indigenous traditions produced a stylistic compatibility.

TRANSITION

It was clear by the mid-1700s that a unique hybrid – a new culture – had developed bringing with it its unique creative vision. The event was marked by the Creole (Mexicans descended from pure Spanish blood) adoption of an Indian event – the appearance of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the Indian Juan Diego on a site associated with the worship of the Aztec goddess, Tonantzin. It was the first time that a vision by a native American was assimilated into the consciousness of the conquering people and the first symbol of a unified, emerging Mexican culture.

Even the horrible devastation done by the Spaniard, Manuel Tolsa, couldn’t stop the tide. Born in 1757 and educated in the severe discipline of the Spanish Academy of San Carlos, he felt it his duty to cleanse Mexico of its “incorrect” Mexican sensibility. To his credit he is responsible for the beautiful neoclassical Cabanas Cultural Institute in Guadalajara and the bronze “little horse rider” on the Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City, but the damage he did far outweighed his contribution to the culture. He smashed and burned whatever didn’t meet his limited aesthetic criteria and imported mediocre architects to correct the “errors”.

However, the coalescing of the cultures had already begun, and nothing could hold back what was to come. Near the end of the century, things had dramatically changed. Artists began to turn to Mexican history for suitable subjects. An interest in cultural values was growing. There was an awakening of Creole or Euro-Mexican sensibility as distinct from Spanish consciousness.

Distortion of anatomy began to emerge. A movement started away from the Baroque, so favored in Europe, towards the more abstract. Painters looked for emotional impact through the manipulation of form and color, and an element of graceful and elegant theatricality started to enter the work. By the 1800s a Mexican school could be recognized – a certain naiveté and distinctive use of local pigments, more allegorical pictures both religious and secular.

Even so, the road was still rocky. The 1800s were marked by years of great internal upheaval and destruction. In 1821 Mexico finally broke from Spain. In 1862 the power of the church was broken by an unassuming Zapotec Indian, Benito Juárez, whose sincere but misguided vision saw churches plundered and relics burned. The church paid heavily for its control and repression, but the arts also suffered since the church had always been its main supporter and patron.

Juarez died peacefully 5 years into his term and was replaced by Don Porfirio Díaz, a man of little taste and great pretension. With the blessing of Porfirio Díaz, the worst of the Victorian era swept through Mexico, and its own colorful heritage became something to be ashamed of. Kitsch had replaced god.

MODERN MEXICO

Fortunately, Mexico’s vital roots, so deeply embedded in its people, couldn’t be squelched for long. By the start of the 20th century, a traditional Mexican drawing method evolved – flat, decorative, and geometric. It drew primarily on indigenous archetypal and folk sources and formed the basis of the primitive aesthetic of several of the modern Mexican painters.

Just weeks before the outbreak of the 1910 revolution, the painter, Dr. Atl, who had changed his name from Murillo to honor his Mexican heritage, used his position with the Academy of Arts to bring together some of his best students. His aim was to incite in them a pride in their cultural past. He inspired the great muralists Orozco and Rivera, who later influenced Siquieros, to get in touch with their country’s rich past.

In 1920, General Alvaro Obregon asked José Vasconcelos, a learned intellectual, how to turn the country literate. Vasconcelos envisioned an integrated nation in which the division between Creoles, Indians, and mestizos would finally be dissolved. He chose mural art to reach the masses. The future muralists had already been inspired by Dr. Atl and were now eager to serve their country.

Mexico had recovered from revolutionary fever and was ready to re-connect with its heritage. Historical and pre-Hispanic paintings with strong emphasis on the Mexican past were favored with the intention of rescuing the ancient indigenous world from oblivion. A group of artists got together and published a manifesto in which they wrote “ Even the smallest manifestations of the material or spiritual vitality of our race spring from our native midst”. This manifesto eventually set the tone for all Mexican artists.

The “Revista Moderna” made its debut. It sought to replace the gods it believed had died. This magazine was extremely influential in disseminating the aesthetics of Latin-American symbolism. Julio Ruelas, the major illustrator for “Revista Moderna” guided the era’s sensibilities. He treated line and chiaroscuro with unprecedented freedom transfiguring them into subtle instruments of his personal imaginative repertoire.

A new breed of artist came onto the scene, free from the bonds of church and academy – Roberto Montenegro with his Beardsly-like images, Julio Ruelas with his tormented underworld, Alberto Fuster, dispenser of beauty in a paradise lost, and German Gedovices, with his allegorical symbolism. All these artists had considerable influence on the young students now entering the Escuela National de Bellas Artes in Mexico City..

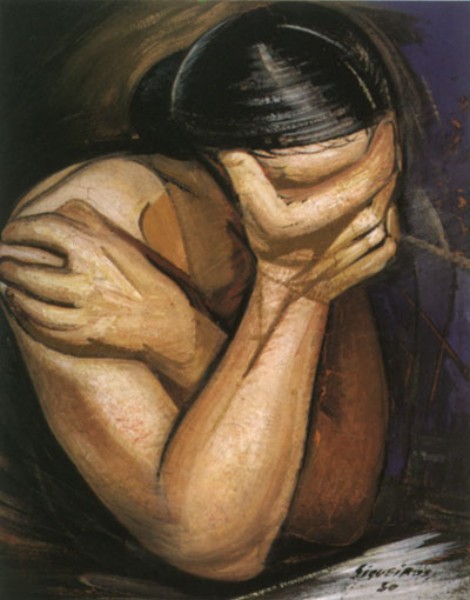

Independent of the Escuela National was Posada, laboring in a workshop only a short distance away. He would come to be known as one of the mythic precursors of the Mexican School of Painting. His work breathed the soul of the people. In his hands the rich Indian past comes alive. The visible and invisible blend and co-exist in a world ruled by passion and imagination, with strong elements of traditional morality expressed in terrifying secular allegories that stress the supernatural. Forms are amplified, attired, or deformed in a quest for greater expression.

Many artists were now coming on the scene whose techniques were European, but whose sensibilities were purely Mexican. Among them were Goitia, Herran, Ruiz, Tamayo, Isquierdo, and Kahlo – each different and each an authentic expression of their heritage. Their work reflects a country of contrasts and oppositions and sudden combinations where colors range from the soft pastels of dust to the saturated intensity of a vibrant, pulsating life force – a country of extremes where life and death walk a thin line and duality prevails. Behind searing intensity one sees the eternal. Behind flat, gentle surfaces, one feels vibrating life.

CONCLUSION

The history of Mexican art encompasses an incredible variety of forms, manners, and styles. Yet, with an attentive eye, you can perceive in this diversity, a certain continuity – not the continuity of a style or an idea, but something more profound and less definable, a sensibility.

I believe it has to do with eons of continuous history imbedded into the collective unconscious of the native people – a collective energy so powerful it couldn’t be repressed or annihilated or over-ridden. The Spaniards tried. They never fully succeeded, nor could they.

Fortunately, there was a stylistic compatibility between the Indian vision and Spanish aesthetics that eventually led to a natural fusion between the two peoples of Mexico, the Creole and the Indian. This union gave birth to an extraordinary body of original and powerful work that speaks to people of all cultures. It is this aspect I’d like to explore in future articles on the arts of Mexico.

Once Upon A Time . . . – The Historical Overview Part 1