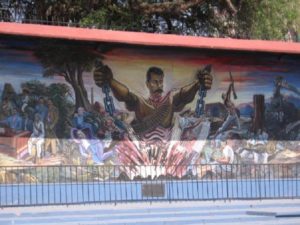

At the heart of liberty is land. Emiliano Zapata knew this better than anyone; his slogan was “Tierra y Libertad!” (Land and Liberty!) This key figure in the Mexican Revolution was born in the heart of the state of Morelos and today you can travel la Ruta de Zapata (The Zapata Route). In the course of one day you can learn about Zapata and his fight against the exploitation of his people in the best way to do that – by moving through his land.

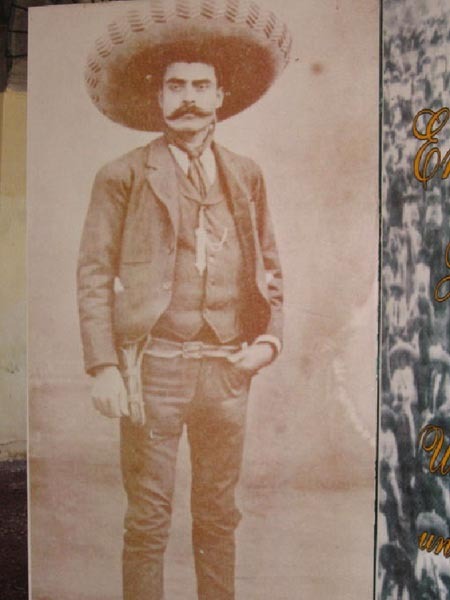

Traveling through his home area you can see both the open spaces through which he rode and the irrigated sugar cane fields that are still in production today. If you speak Spanish, you can talk to the people who still inhabit his land, living their daily lives, preserving their history, and preparing their message for future generations. You will come away knowing that Zapata was a real man of great strength, determination, and ideals who lived his life as a Mexican, defining himself between the extremes of poverty and Spanish class-ism; excelling in horsemanship, leadership, and just as macho as they come.

Emiliano Zapata a Powerful Force

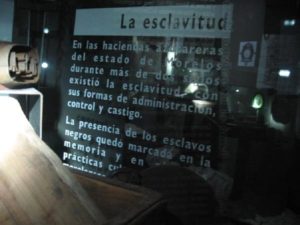

On August 8, 1879, in the middle of the rainy season, a powerful force came into the world in the usual way. Gabriel Zapata and his wife Cleofas Salazar named him Emiliano Zapata Salazar. He was the ninth of ten children and grew up learning the ways of farming corn and dry season watermelons as well as raising cattle and horses, in the scrub forests that surrounded his home in Anenecuilco, Morelos. His family was not rich. He lived with them in a two-room adobe house and dressed in the traditional white manta clothing. Actually, though, he was quite lucky. His father owned land and the family was able to make a living without getting sucked into debt slavery on the hacienda sugar plantations that were increasingly being given control over the land in the regions surrounding his home town.

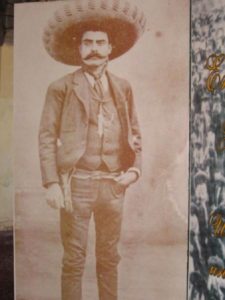

Emiliano grew into an expert horseman and dressed in the tight legged trousers, suit coat and vest of a rich man as soon as he could afford it. In the museum in Anenecuilco there is a story about him putting real coins onto his first pair of suit pants. Emiliano was trusted by the people of Anenecuilco and at age 30 (in 1909 one year before the start of the revolution) he was elected to a leadership role by his community. From this point on he never backed down from his fight to return the land to the people. Sometimes this can seem like ancient history, but it’s not. Our grandparents could have known Zapata.

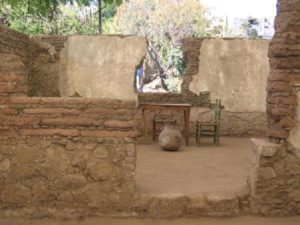

Zapata’s Home and Another Powerful Force

In Anenecuilco, Morelos you can see the walls that sheltered Emiliano and his family as he was growing up. Their solid adobe blocks give off a comforting stillness from beneath a soaring white tent within the grounds of the Museo Casa de Zapata (House of Zapata Museum). This is the first thing that you will see as you pass through the gates at the entryway to the museum. In the air there is a faint scent of cattle, just as there would have been when Zapata walked there.

The curator of this museum, Lucino Luna Domínguez is another powerful force born in Anenecuilco, and I found him watering the museum’s small botanical garden. The groundskeeper had a problem with his eyes and Don Lucino had volunteered to take over the watering for the day. He welcomed me calmly and within a few moments of talking to him, I knew that the museum was his passion. He’s been curator for 13 years now and is personally involved in its growth as well as its relationship with the community of Anenecuilco.

On the Sunday that we visited, there was a group of young people painting at easels set up in the shade of a tree in what used to be Zapata’s “yard.” Their presence there wasn’t coincidental; they were there because of Don Lucino’s vision of what the museum is and can become for his community. He explained to me that they were painting illustrations of local legends as part of a project to create a book. He tells young people the stories and it’s their job to paint events in each one. This is just how Don Lucino thinks. He has this uncanny understanding of how to make history valuable in the present for people of all ages.

He says that the town of Anenecuilco is fighting to show the world the unknown Emiliano Zapata. During my visit, he shared some details over which he disagrees with the standard historical account of Emiliano Zapata. These variants are based upon his own research of documents stored by the church and interviews he has conducted with the elders of Anencuilco. One such detail is the number of men who accompanied Zapata and his brother as they first rode out to engage in armed conflict. He says that at that time there were 300 people in the small town and that 25 men left that day. Apparently, the “official” version says that only three rode out. This would be an insulting inaccuracy to the people who, as children, watched the men gather and mount up.

As we stood in the garden, the newly rebuilt, L-shaped museum was to our right and behind us. Everything inside is carefully planned. The air is naturally cool. The lights are low with the displays illuminated by carefully designed lighting. You weave through loosely separated “rooms,” which first describe the people of Anenecuilco and their horrendous loss of land, water, and freedom to the sugar plantations, called haciendas. Next, Emiliano’s history and life is described within this context.

The contextualization was one of the two things that really impressed me about the museum. So many museums in Mexico are a series of items with signs underneath that leave the reader with more questions than answers (even if you read Spanish perfectly). I’ve often joked about the state-the-obvious style of Mexican museums. You are looking at an ancient piece of pottery with some black designs painted on it and the sign says, “Pre-Columbian pottery with black designs typical of this region.” Museo Casa de Zapata doesn’t fall into this trap.

As you study items from the era and old photos of Zapata, you are carried along by guitar music from a film that you see in the second to last room. Standing in the same room as Zapata’s guns and his saddle you watch this movie, projected onto a curved, white wall with time-advance scenes using historical and current photos, an aerial shot of the town and real people’s voices. The movie was made by El Grupo Mundo with the help of SECTUR (the state tourism department). Don Lucino took the filmmakers out to get the shots they needed and, even though he doesn’t say it, I think he had more than that to do with the content.

Don Lucino has made it an important part of his mission to gather and preserve items belonging to Zapata and his men. He goes personally to people, many of them elders, and explains to them how important their items are in preserving the story of Zapata and Anenecuilco; that they will last forever, long after we have departed this life. He is particularly glad to have the .30.30 carried by Zapata on that first day, donated to the museum by Marcos Manuel Suárez Gérard, the secretary of tourism. He also has his saddle mounted on a tall stand for all to see (also donated by Marcos Manuel Suárez Gérard). I almost talked him into letting me take a picture of him resting his hand on this saddle to accompany this article, but he decided to abide by the no-flash rule in order to protect it and I was without a tripod.

Don Lucino had come inside to tell a little about the items in the museum. We were talking and two little children had brought their dump truck inside to play in the open area in front of the curved screen. He stopped talking to say, “Hey kids, go play in the hallway outside, please.” The understanding, gentle tone of his voice impressed me. He wasn’t “the man in charge,” he was a kind adult who wants everyone to be comfortable in his museum. He is skilled at teaching people and soon had a small audience looking with appreciative glances at the artifacts and asking questions. He uses a story-telling style that is special to the oral tradition of Mexican country people, which you have to hear to fully appreciate.

The guitar music made my experience in the main part of the museum relaxed and pleasant, but my favorite room in the museum is the last one. It is a small theater, with benches, and black curtains keeping the ambient light out. There is a touch-screen monitor on the wall where you select the movie you would like to see. When I walked in, there were elders talking about what they remembered about Zapata. The image is about 8 feet by 10 feet and large enough to relax and watch. My favorite was the clip of Zapata’s step-daughter, now probably in her 70s. She describes herself as his daughter’s sister and shows us a photo of him. The scene was shot in an outdoor kitchen of a tiny Mexican house. Just like Don Lucino, she’s the real thing.

I asked Luna Domínguez how he became interested in Emiliano Zapata. He told me that when his grandfather Fidel Luna Franco took him to work with him, he would tell him the stories of his days with Zapata. Mr. Luna Franco planted his fields and fought along side of Emiliano Zapata. Through his grandfather’s oral tradition, Don Lucino was kept in touch with these experiences. To Don Lucino, Emiliano Zapata is not just a historical figure; he is a real man who lived a real life.

Not only does this Casa Museo teach us about Emiliano Zapata, thanks to Don Lucino Luna Domínguez, it teaches us about history itself. What is history? Who should tell it? What form should history take? Should it be oral, written, or pictorial? How does history affect us in our daily lives?

Next month read Part 2 – His Heart Stopped Beating, along with full driving directions so that you too can retrace the Zapata Route.