Mexican History

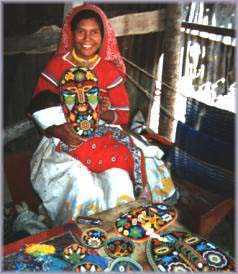

Huichol art has come a long way since Carl Lumholtz first recorded it in the late 19th century. In previous articles, we looked at some of the changes that have taken place over the years in the form and function of Huichol art, particularly the transformation from a strictly religious function to a commercialized folk art. Here we shall conclude with a few more samples of Huichol art.

Originally masks were used for magical purposes or to frighten enemies in battle. While such masks are no longer made or used for this purpose, you may come across beaded or painted masks for sale. Today they are a relic of early Christian teaching used by the Huichol in ceremonies, for example, during Semana Santa (the week preceding Easter) to represent Europeans or foreigners.

But this does not mean they are not “authentic;” rather they represent a stylistic variation in the tradition and a syncretism between Huichol (Mesoamerican) religion and Christianity. The Huichol take an eclectic view of religion based on their experience with Conquistadores and later foreign invaders of their land and culture. Obviously the alien gods were powerful enough to conquer Mexico. Therefore it only makes sense to incorporate foreign gods (Catholic saints) into the Huichol pantheon. The more powerful deities you have on your side, the better.

I witnessed something similar among the Yukon Indians. We spent summers in the fishing camp at Klukshu Lake north of Whitehorse where we lived. One Sunday, my Indian friend Frank Smith told me they were expecting missionaries from three different religious denominations: a Protestant minister, a Catholic priest, and their own evangelical preacher. Frank saw nothing strange about this. He said: “We gonna be good people. First, the English man comes, then the Catholic man, then our Reverend Lee. We don’t have money to give them, so we give them dried fish.”

Associated with masks is the custom of facial painting. Lumholtz recorded a wide variety of facial markings used in ceremonies and associated with various deities. The earlier patterns were very elaborate.

A Huichol peyote festival

I attended a peyote fiesta in Las Guyabas in the Huichol sierra a few years ago. During a late evening ceremony, I sat off to one side of the gathering feeling rather isolated, until an unusually tall Huichol woman, who seemed to exercise considerable authority, came over to me and offered me tejuino, the local brew. Her face was painted with yellow dots, which I recognized as peyote symbols. Not as elaborate as in Lumholtz’s day but impressive. After that gesture, she invited me into the circle for food and drink with the rest.

The Huichol used two types of jícaras,or bowls made from one half of a hollowed-out gourd, one for ordinary household use and the other for ceremonial purposes. Today small beaded bowls are made for sale. But traditionally the designs inside the bowls represented different deities in the Huichol pantheon.

At the peyote fiesta, I observed the sacrifice of the bull inside the calihuey (Huichol temple) and the ceremonial use of the prayer bowl. A woman performed the sacrifice by slowly inserting a knife in the bull’s throat as it lay tethered on the floor of the calihuey. As the blood oozed out, she held out the bowl to catch the blood. There were several shamans present in full ceremonial regalia. When the bowl was full, one anointed the foreheads of the other shamans with smears of blood and then scattered blood at various places around the calihuey as protection against evil.

In previous articles, I referred to my late friend Gregorio’s comments on the elaborate clothing worn by Huichol men today. This, of course, is made possible by the skill and artistry of the Huichol women in embroidery.

Motifs in Huichol art

Traditionally most designs or patterns were not made simply for the sake of decoration but rather for religious or symbolic purposes. Even the decorations embroidered on belts and clothing based on nature and natural objects in the plant and animal world have significant meaning. For example, woven belts, sashes, and ribbons represent rain-serpents.

The Huichol tend to see snakes or their representations in many natural objects. This is perhaps not too surprising given the importance of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, in the religion of the Aztecs, whom, incidentally, the Huichol claim as their ancestors. In Lumholtz’s day snakes for the Huichol represented prayers for good crops, health, and long life.

The designs may become so conventionalized that they are unrecognizable to all but the original artist. But even if the original meaning is forgotten, they are still thought to have magical powers. Typically there is great variety in designs, although some women copy from others, with slight changes.

With regard to copying designs, I used to have two books containing photographs of Huichol yarn paintings. I no longer have them. Guess who borrowed them and never returned them? Why, my Huichol artist friends who wished to copy some of the patterns. Who knows, maybe one day I’ll go back to the Huichol sierra and find my books again.

The last item a Huichol abandons if he exchanges his traditional clothing for modern western garb is the ubiquitous embroidered pouch or side bag. They are woven in one piece and then folded over and sown up the sides. A common motif is the double water-gourd design, also woven into belts, where it gives the impression of snake skins. Another favourite design is the double-headed Royal Eagle, a symbol which has nothing to do with the double-eagle heraldic devices of Europe. However, some critics have pointed out that sometimes the eagle is shown wearing a crown, which, they say, indicates European influence. Possibly this is associated with the Catholic version of the Virgin Mary with which the Huichol would have been familiar.

Here we shall touch on only one more traditional item, sculpture. On one of his exploratory expeditions, Lumholtz visited the sacred cave of Te-akata, birthplace of Tatewari, the God of Fire. Near the entrance to the god-house, he observed the statue of the old god made of solidified volcanic ash. In 1983, I attended an exhibition at the Regional Museum of Guadalajara put on by La Sociedad de Amigos del Museo to reaffirm, rescue, revive, and spread abroad the ancestral culture of Jalisco. Featured was the work of Pablo Taizán de la Cruz, a Huichol mara’akame (shaman) from Tuxpan de Bolaños, Jalisco, who displayed his large stone sculptures of various Huichol deities. It was a gala affair attended by politicians and local dignitaries. Pablo was the man of the hour, but I wonder how much of the show was mere lip service (just my opinion).

Tatewarí (“Grandfather Fire”) and Nakawé (“Our Grandmother Creator”) are still two very important deities often represented in stone and other media, as well as in the yarn paintings. Tatewarí is a very ancient Mesoamerican god, the god of fire, or the god of the centre. He is one of the deities of the Dry Season. Nakawé is the principal goddess and the most ancient. As mother of the gods, the creator and destroyer of all that exists, she is one of the deities of the Wet Season. The Huichol may be highly religious, but they are also very practical and have no compunction whatsoever in selling representations of their deities, which is really no different than the sale of religious icons at a Catholic cathedral. I once tried to sell a beaded statue of Nakawé for a Huichol friend. Unfortunately sometimes these statues are misrepresented as Huichol “dolls.”

An art in evolution

The artistic tradition remains much the same, but the particular forms and the stylistic expression have changed dramatically since the days of Lumholtz. However, as I have tried to show, the adoption of commercially produced media, such as glass beads and coloured yarn, and changes or developments in stylistic expression do not necessarily detract from the authenticity of an art object. The main purpose in commercial Huichol art is to enable at least some of the people to retain their language, religion, and customs by continuing and expanding traditional art forms as an alternative to wage-slavery in the outside world. However, the extent to which a tradition can change and still be regarded as such is perhaps debatable. On one of those extremely rare visits from our relatives in Canada, my sister-in-law, unimpressed by the religious and symbolic meaning of the Huichol art in my own personal museum, asked me why the Huichols didn’t make something useful, like a beaded piggy bank. Half jokingly, I mentioned this to a Huichol friend. Surprise, surprise! I now own a beaded piggy bank.

Some items of Huichol art are definitely non-traditional, such as beaded eggs intended for Christmas decorations; others, such as masks of the sun and moon, are borderline traditional. Beaded Jaguar heads are an important symbol in Mesoamerican religion and by no means confined to the Huichol. The bead and yarn paintings are becoming more and more complex, with some risk of becoming more decorative than symbolic or religious. Yarn paintings depicting aeroplanes and skyscrapers may perhaps safely be deemed non-traditional.

Survival of the Huichol language and culture does not, of course, depend solely on the commercial viability of Huichol art. Although most Huichols are artisans of one kind or another, relatively few can make a living from this source alone. Besides, there are too many middlemen to rake off the profits. While the young people need to understand the world around them in order to protect their own interests, they also need more books in Huichol about their own culture in order to foster and preserve the best of their traditional world. This is not unrealistic or over-optimistic.

Surival of an ancient culture

On my last visit to Canada, we visited a Mennonite community in southwestern Ontario. The people range from very liberal to extremely conservative. The Old Order Mennonites still drive a horse and buggy and work their farms using “old-time” implements. Some refuse to use electricity or other modern “conveniences.” They are excellent craftsmen and produce fine furniture for sale. While they maintain their own beliefs and lifestyle, they are also coordinated with the outside world and thus avoid conflict.

I like to think the Huichol can survive in a somewhat similar manner. To some extent, they are protected by the remote rugged mountain terrain in which they live, although even there they are still under siege from outside exploiters and land developers.

Only time will tell.

- Huichol art, a matter of survival I: Origins

- Huichol art, a matter of survival II: authenticity and commercialization

- Huichol art, a matter of survival III: motifs and symbolism