Did You Know…?

The American White Pelican is Mexico’s largest bird, while its relative the Brown Pelican is one of the most fun to watch.

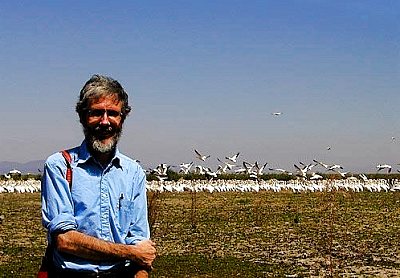

photo: John Mitchell, Earth Images Foundation

The two birds prefer different habitats and are rarely seen together. The American White ( Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) is usually found on inland freshwater lakes, while the Brown Pelican ( Pelecanus occidentalis) is a coast-dweller. There are many other significant differences between them, as we shall see.

The American White Pelican

Thousands of these magnificent birds visit Mexico each winter, taking up seasonal residence in large flocks (several hundred strong) on inland lakes such as Lake Chapala. The White Pelican, which breeds in Canada and the northern U.S., should be the official North American Free Trade bird. It is the largest of the many migratory birds linking the three NAFTA countries together, moving freely between them, requiring neither passport nor permit.

Completely dependent on fish, White Pelicans occupy the top spot in the lake’s food chain; this makes them an excellent indicator species for judging the area’s environmental health. Unlike Brown Pelicans, which dive for their food, White Pelicans swim gracefully on the surface, scooping up fish in their massive beaks. They fish co-operatively. It is great fun watching them fan out into a semi-circle and then slowly close in on lunch, dipping their cavernous beaks into the water at the same time in perfect synchronicity. There is a clear lesson here for us: working together is far more efficient than working independently.

photo: John Mitchell, E.I.F.

White Pelicans are long-lived, though each female lays only one or two eggs a year. This may be their Achilles heel. If their population ever decreases, it could take decades for their numbers to recover.

Not everyone likes pelicans. Some fishermen complain that each adult pelican consumes up to a kilogram of fish daily, reducing their potential catch. However, studies in Europe have shown that pelicans consume a higher percentage of diseased fish than would be expected in the overall fish population. Hence the pelicans’ culling of fish shoals may actually bring the fishermen long-term benefits by improving the quality of fish stocks.

Several centuries ago, it is recorded that any fisherman on Lake Texcoco, near Mexico City, who saw a White Pelican, locally called a pavo del agua (water turkey) or corazón de la laguna (heart of the lagoon) had just four days in which to catch it. Failure meant the fisherman was close to death. Success resulted in the pelican’s stomach contacts being examined. Feathers or green stones foretold good luck, charcoal bad luck. The bird was then plucked, cooked and eaten. Fortunately, pelicans are now protected by international agreements.

One of the best places in the world for observing White Pelicans is their winter hide-away on the southern shore of Lake Chapala, near the small fishing village of Petatán. They are very photogenic and, in Petatán, you can safely approach much closer than is normally possible in their breeding grounds further north.

While viewing them, watch for their characteristic behaviors – an ungainly take-off from the water (followed by alternate gliding and flapping flight), their cooperative fishing technique, and don’t be surprised by their virtual silence. Occasional whining grunts are the most you are likely to hear. Conscientious visitors will be just as quiet, taking care not to disturb the pelicans in any way – only fair considering how far they’ve flown to get here. The White Pelicans are so numerous in Petatán each winter that the locals call them borregones, the literal meaning of which is “large sheep”.

The Brown Pelican

Brown Pelicans diving for food are one of most spectacular sights on Mexico’s 10,143 kilometers (6,300 miles) of coastline. The pelicans’ large size, graceful flight, and easily caricatured shapes are an attraction throughout their range.

Brown Pelicans may look somewhat ungainly, even comical, when in flight, but their diving abilities would easily win them Olympic gold medals. Cruising up to 25 meters (80 feet) above the water, they dive vertically into the ocean when they spy a fish, their impact with the water cushioned by air sacs beneath their skin. While under water, they scoop up 9.5 liters (2.5 gallons) of seawater into their huge beaks, together with the fish. The, they tilt their heads forward to drain the water, before throwing them backwards to swallow the fish whole. Perhaps most amazing, they have the ability to abort a dive within a few millimeters of the waves if they think they are going to miss the fish.

Not surprisingly, learning to dive like this is one of the most dangerous periods of their early life. Many young pelicans die before their first birthday, still trying to master the art. Those who graduate with diving honors may well live for more than 20 years. Of the eight pelican species worldwide, only the Brown Pelican is truly marine, catching its food in this method.

Gregarious brown pelicans hang out at the beach in Los Ayala, Mexico. © Christina Stobbs, 2011

Gregarious brown pelicans hang out at the beach in Los Ayala, Mexico. © Christina Stobbs, 2011

Pelicans have existed as a species for at least 30 million years, maybe longer, but barely 40 years ago, their future was in grave doubt. The California population of Brown Pelicans suffered a drastic decline in reproduction rates; this was subsequently shown to be due to excess amounts of DDT in the environment. This pesticide saved millions of human lives (it was used to wipe out mosquitos carrying yellow fever and malaria) but its residues, including DDE, were fat soluble. They entered the birds’ ecosystem as agricultural run-off flowing into the ocean to be absorbed by plankton, eaten in turn by fish. DDE levels in Brown Pelicans reached up to a million times more than in the surrounding environment, causing the pelicans to lay sub-standard, soft-shelled eggs, easily crushed during incubation. For instance, on Anacapa island in 1969, only 5 chicks hatched from almost 1300 nesting attempts! In the eastern U.S., the story was repeated. Louisiana, the “Pelican State”, had no pelicans at all nesting there for several years in the 1960s, though the birds were later reintroduced from Florida.

It took until 1972 for federal regulations to limit the use and dumping of DDT. Pelicans gradually purged their systems of DDE, and now their fortunes have improved considerably.

Brown pelicans nest on the ground or in trees, and usually lay three eggs. Both males and females share the 30 days incubation period. Newly hatched chicks are decidedly ugly, with reddish brown or purplish black skin. They later get a white down. The chicks remain in the nest for about five weeks, and eat up to a third of their body weight in fish every day. Their feeding habits are revolting. The chicks, unable to fly or leave their nests, force their parents to regurgitate food for them by thrusting their beaks into their parents’ mouths. Larger chicks looks as if they are being swallowed alive by their parents!

To fend off would-be predators, the chicks form groups known as creches. The young pelicans can squawk, but the adults neither sing nor call, and instead have developed a complex series of gestures to communicate with each other.

While the chicks are in the nest, they have to be protected from extreme temperatures of up to 36-40 oC. The adults protect them by a process of rapid panting which cools their skin, and by taking care to position themselves so as to shade the nest. As the day progresses, the birds rotate their bodies – it is quite a sight to see several hundred birds perfectly aligned in the same direction!

Obviously, seabirds such as the Brown Pelican are good monitors of the marine environment and their numbers provide a way of judging our impact on a coastal area. Pesticide residues have now been detected in marine life as far away as Antarctica, so our effects in one area may well reach far beyond where we first think. Let us hope that Brown Pelicans will continue to rest on offshore rocks, sit on moored boats, and dive for their food off Mexican beaches for many centuries to come!

Copyright 2006 by Tony Burton. Photo copyright as indicated. All rights reserved.