Frida Kahlo was a talented artist considered by many to be a modern master. She also was a tough lady, fighting physical adversity from early childhood. Her artwork provides a look into her tormented body and soul. Her colorful, graphic paintings mirror her life story. Both are controversial!

Frida Kahlo was a talented artist considered by many to be a modern master. She also was a tough lady, fighting physical adversity from early childhood. Her artwork provides a look into her tormented body and soul. Her colorful, graphic paintings mirror her life story. Both are controversial!

She holds several firsts as a Mexican artist: first to have a work purchased by the Louvre in Paris, and first painting sold for more that $1 million. Her paintings can be seen in several leading museums in North America and Europe, and in the Frida Kahlo Museum in her former home, the Blue House, in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City. The Dolores Olmedo Patiño Museum in Mexico City houses an important collection of works by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, who twice was her husband. Frida made little money during her short lifetime (1907 1954) as her works did not sell well and she gave many away as gifts. Ahead of her time, it was not until the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s that her art was “discovered” and she became a popular figure.

Frida Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907 to Guillermo Kahlo, a Hungarian German immigrant, and Matilde Calderón, a native Mexican of Spanish and Indian descent.

She was the third of four daughters. Her father, whose original name was Wilhelm Kahi, had come to Mexico in 1891 with no particular prospects after epileptic seizures cut short academic studies in his native Germany. He took up photography when he entered business with his father in-law. Shunning portraits, his specialties were buildings and structures. Fortunately he was fairly successful, and in 1904 he received an appointment as official photographer of architecture for the Mexican government under Porfirio Diaz, a career cut short by the Revolution in 1910.

In 1913 Frida contracted polio, which crippled her right leg. Recovery of its use took almost a year for the six year old, and children’s taunts about her limp made her extremely self conscious. Sharing a burden of stigmatizing illness with her father caused them to become very close.

He was withdrawn with all but Frida. Together they practiced soccer and various athletic activities in order to build strength in her weakened leg. They went on nature walks, collecting specimens to view under his microscope. They shared intellectual and creative pursuits, including painting. Frida had a much different relationship with her mother. A strict disciplinarian, Frida called her “El Jefe.”

With encouragement from her father, in 1922 Frida entered the prestigious National Preparatory School, a part of the revitalized National University. Interested in a career in medicine, she was one of only 35 females in a student population of 2000. By this time she was an outrageous extrovert, tremendously enjoying any attention at school. Soon after starting there, she observed then 36 year old Diego Rivera working on his commissioned mural “The Creation.” She spent many hours watching him, and sometimes heckled him, even calling him Panzón, “fat belly!”

Frida became part of a group called Las Cachuchas, after the caps they wore, comprising nine precocious intellectuals specializing in pranks as well as serious study. Friends for life, some were later featured in Kahlo paintings. One was Alejandro Gómez Arias, Frida’s first boyfriend. She wrote him many passionate letters, some dotted with small drawings. A 1922 letter contains one of her first self portraits. Gómez Arias became a leading educator in Mexico, and the others in the group had illustrious careers as well.

On September 17, 1925, the young lovers were riding a bus home from school when tragedy struck. The bus collided with a streetcar and was demolished. Gómez Arias was thrown to safety but Frida was not so lucky: a steel guardrail had penetrated her lower torso. Care was not administered immediately because she was set aside with the other gravely injured not expected to live. But somehow she survived, despite the delay and extensive injuries. An elaborate body cast was required to treat her fractured skeleton, which included the spinal column broken in three places, fractured pelvis and collarbone, two broken ribs, broken right leg and crushed right foot. For the rest of her life she had bouts of pain, weakness and ill health. Regardless of what weakened her body, her fight against debilitation strengthened her will to live life to the fullest.

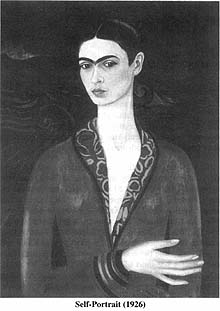

No longer a serious academic, Frida had started art studies shortly before the bus accident. She took up painting as a means of therapy during her long recovery. Symbolically, her first work was a self portrait, the type of painting she favored and for which she became most noted. The later self portraits show the same somber stare but with a variety of colorful native Mexican attire. Insightfully she later revealed, “I paint self portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

By 1928 Frida was socializing with the artsy crowd in Mexico City, which along with Paris and New York City, was a center for the developing Bohemian lifestyle. At a party in 1928 she was again introduced to Diego Rivera, who by then was an acclaimed artist. She asked him to critique some of her paintings. After Rivera responded favorably and encouraged her to continue, they began seeing a lot of each other. They married on August 21, 1929. Twenty years her senior, it was his third marriage. Each continued to have numerous affairs, lovers, and dalliances. After ten tumultuous years they divorced, then remarried one year later. Frida once professed, “I have suffered two great accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other accident is Diego.”

In late 1930 Diego Rivera was commissioned to paint some murals in San Francisco. While there Frida painted several portraits, one of which, Luther Burbank, gave an indication of her growing surrealistic tendencies. The couple was in Detroit in 1932, Diego working on a mural at the Institute of Arts, when Frida had a devastating miscarriage. Shortly thereafter, she portrayed the experience in the fanciful painting Henry Ford Hospital. Back in Mexico later that year, Diego suggested that in addition to portraits, she paint episodes from her own life . The first one she entitled My Birth. Other dramatic works followed: My Dress Hangs There (1933), My Nurse and I (1937), Memory (1937), What the Water Gave Me (1938), The Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), The LittleDeer (1946), among others. In 1935 she painted A Few Small Nips probably in response to learning that Diego had had an affair with one of her sisters. These works, as with all of hers, have to be seen to be appreciated.

The self proclaimed founder and leader of Surrealism, André Breton, was captivated with Frida’s work, praising her as a self invented Surrealist. Frida thought otherwise, claiming that she painted only her own experiences, “I never painted dreams, I painted my own reality.” It was a stark, bloody reality, using symbols of injury and torture to show her own physical and emotional pain. There is not a smile on any self portrait, and on two she wears a necklace of thorns!

Diego Rivera was an ardent communist and Frida Kahlo had embraced communism before their marriage. Sometime in the mid 1930s, Frida dropped the e in her name and used only the Spanish spelling, a form of protest against Hitler and Nazi Germany. In 1937 Leon Trotsky, a leader in the Soviet Revolution later exiled by Josef Stalin, came to Mexico and lived for two years with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

Another affair ensued. Trotsky moved out but a year later was assassinated, bringing the artist couple under close police scrutiny for a while.

In 1943, to earn money to be financially independent from Diego, Frida began teaching painting at the public secondary arts school, La Esmeralda. Her health declined in 1944, and from 1945 into the early 1950s she taught at home. With the onset of constant pain in 1944, she began a diary. It contains not only her thoughts over the last tell years of her life, but also many sketches, drawings and small paintings.

The diary resides in the Frida Kahlo Museum but a reproduction with translation to English was published in 1998 as The Diary of Frida Kahlo, An Intimate Self-Portrait.

At long last, in early 1953, Frida Kahlo had a one-person show in Mexico City. It was a success, mainly because Frida attended the show against doctors’ orders, brought by ambulance and holding court in her own four-poster bed set up in the gallery. She told Time Magazine, “I am not sick. I am broken. But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

But soon thereafter her diary said otherwise. After her gangrenous right foot was amputated in August 1953, her entries became more morose and she talked of suicide. Finally, on July 13, 1954, Frida Kahlo died. The cause of death was reported as pulmonary embolism, but many of her friends believed she killed herself with an overdose of pain killers. Moreover, the last entry in her diary says, “I hope the exit is joyful and I hope never to come back Frida.” And the last drawing is a black angel rising, an angel of death?

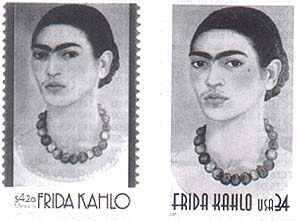

On June 21, 2001, both the United States Postal Service (USPS) and the Servicio Postal Mexicano (SEPOMEX) issued a stamp to commemorate Frida Kahlo. A USPS press release on May 21 stated, “This is the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp.” As you recall, it created quite a stir in the U.S., mainly because of her lifestyle and membership in the Mexican Communist Party. By my count, published letters to Linn’s Stamp News were about evenly divided between support and contempt for the issue. However, I do not know how many letters were received overall.

Although the stamps were not a joint issue, each features the same painting, a self portrait from 1933. Comparing the two with the painting, I think neither does justice to the original. In the SEPOMEX portrait her skin is too pale, lacking vitality, the background is too dark, and her dress should be yellow, not white. The USPS rendition has the skin tones too orange. The USPS pane of 20 stamps also has a photograph of Frida Kahlo on the right selvage (see page 54) a photo taken in New York City in 1938 by Nickolas Muray, a well known fashion photographer and one of her lovers. These pictures show but some of the color and exuberance found in her artwork and personality. For a better view of Frida Kahlo’s talent to use symbolism, portray beauty and suffering, or to evoke pathos, I urge you to check the references below.

Also, an Internet search using “Frida Kahlo” will bring up many sites showing her work. The intense but colorful depictions just might be inspiration to learn more about the complex person that was Frida Kahlo.

References

- Alcántara, Isabel, and Sandra Egnolff, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Pegasus Library, Prestel Verlag, Munich, 1999.

- Hardin, Terry, Frida Kahlo, A Modern Master, Todtri Book Publishers, New York, 1997.

- Herrera, Hayden, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, Harper and Row, New York, 1983.

- Herrera, Hayden, Frida Kahlo: The Paintings, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 1991.

- Linn’s Stamp News, Vol. 74, 2001: issues of June 11, June 25, July 16, August 6, August 20.

*This story was originally presented in the January 2002 edition of Mexicana, The Journal of Mexico Elmhurst Philatelic Society International and has been reproduced here with permission.