“Would you like to carry the casket?”

I blinked vacantly, thinking perhaps the 104-degree heat was melting my brain-or maybe my shaky Spanish was failing me (that seemed more likely). “¿Como?” I asked, scarcely believing my ears. The young Zapotec Indian straining under the load motioned again to the small coffin. “Would you like to help carry this?”

It was not the kind of thing the average tourist hears. Then again, Zapotec funeral processions aren’t your average tourist activity.

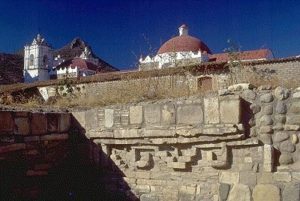

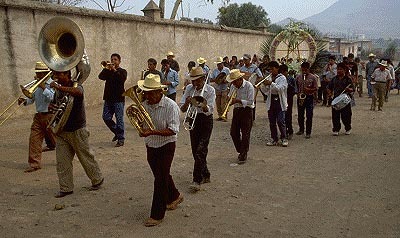

An hour earlier, curiosity about the out-of-place sounds of brass band music led me through Teotitlàn del Valle’s dusty streets to discover its source. It was a brass band, trudging slowly before a group of mourners as a funeral procession left the town’s red-domed 17th century mission church.

I was torn between the tantalizing photographic potential and the voice in my head that said, “What are you thinking?! You can’t go in there with both guns blazing and start taking pictures of someone’s funeral? Those people are mourning – respect that!”

The skirmish in my head was brief but intense. In the end, I compromised, deciding to take my camera and walk up behind the procession, letting events unfold. Maybe I would take pictures, and maybe I wouldn’t. If I sensed that my camera and I weren’t welcome, I could just walk past, pretending I was on my way elsewhere. Whatever happened, I couldn’t simply turn my back on a potentially incredible experience without exploring it a little more. It was worth some risk.

Ambling up behind the stragglers, filled with trepidation at plunging myself in where I clearly didn’t belong, I joined them. An old man, his keen eyes and deeply etched face shaded by the ubiquitous cowboy hat, looked at me quizzically as I greeted him. Suddenly, an enormous smile burst across his face. What it lacked in teeth, the smile more than made up for with warmth and welcome; my apprehension began to dissolve. The warm hospitality I had seen throughout Mexico apparently extended even to gringos crashing funeral processions.

“Go ahead, take pictures,” he reassured me. “Es mi sobrino,” he said, motioning toward the casket. He’s my nephew. “Only 54 years old. But he was sick.” Even with this unexpected permission, I felt uneasy. I decided to wait and turned my attention to the procession that plodded on beside me.

A strange blend of wailing grief and casually cheerful festivity lent a surreal cast to the occasion. The thick sweetness of copal, a ceremonial incense, enveloped the mourners. The women’s brightly embroidered smocks countered the solemnity of the occasion. Grey shawls hid vibrantly colored ribbons woven through long braided hair. Men walked in small clusters, some clad in button-down shirts and cowboy hats, others-mostly younger-sporting t-shirts and baseball caps.

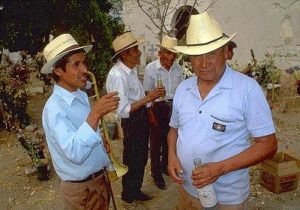

Soon, three more men fell in beside me and my newfound friend. I noted with mild dismay that they were carrying a cooling bucket of water containing three bottles of mescal, a close cousin of tequila. I eyed the bucket nervously; past experience told me that I was just about to be cornered for an oh-too common occurrence. I was right.

A work-calloused hand soon plunged into the water to retrieve a tiny plastic cup and a clear, hand-painted glass bottle, pouring a shot and holding it out expectantly. I protested mildly. “Please,” he implored. “Please drink one.” My efforts to “just say no” were clearly doomed. Bracing myself, I tossed it back and with slightly watering eyes declared crisply, “Mmmm. Muy bueno.” They laughed in approval and immediately poured round two. “Not yet.” I protested again, trying to buy some time, but the man holding it out insisted solemnly, “No, please. You must. It’s tradition. You have two hands, so you must drink two.” I caved in, not knowing if this was really tradition, or simply a ploy to get the tall, pale gringo in their midst boozed up. “OK,” I said, “but remember, I only have two hands!” and shot it down. They laughed and countered, “Oh, but you also have two feet! That makes four.”

Walking, talking and drinking with my new amigos, I felt myself passing from outsider to welcome addition.

As I fended off more good-natured advances from the mescal pusher, one of the pallbearers asked if I would like to help carry the casket. They wanted me to be a pallbearer! Suspecting that the primary reason was my giant stature in their midst (despite the fact that I’m a fairly average 5’10”), but honored nonetheless to be so completely taken into the group, I took my place.

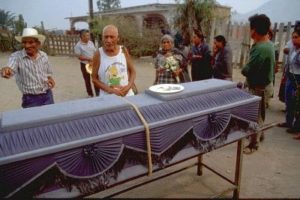

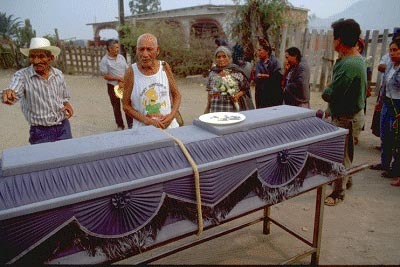

Straining under the surprising weight of the small casket, we shuffled behind the soft pastels of an enormous wreath of flowers. Fancy tight pleats of faded grey cloth hid the modest construction of the coffin. Just short of the cemetery the procession paused, offering a welcome opportunity to set the casket down. The priest, a squat man clad in a maroon polo shirt, murmured in Spanish from behind his bushy mustache as he read from a worn pocket-size notebook.

A bald old man with a dignified bearing took center stage, first placing a plate of coins on the casket, then a bowl of water containing a small sprig of a freshly cut plant. His gleaming white tank top, featuring Bart Simpson giving the world the finger and proclaiming “Fuck off, dude!” seemed at odds with the solemnity of the occasion, but no one seemed to notice.

I relinquished my place at the casket and began taking pictures. Suddenly I didn’t feel like an intrusive outsider, there to gawk and then move on. In the valleys of Oaxaca, a camera is often met with a shake of the head or an outright scolding. This time, nobody raised an eyebrow. Perhaps they could sense that this wasn’t trophy photography. It was rooted in a genuine interest in them, who they were, and how they lived their lives. In a limited way, they had welcomed me into their world.

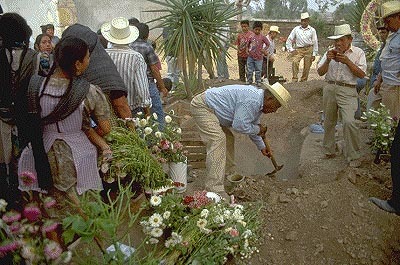

With hat-in-hand solemnity, the procession filed slowly through the cemetery gate to the stark emptiness of the newly dug grave. Splashes of color, bouquets left in memory of others already laid to rest, relieved the monochrome grey of the bare earth inside the cemetery walls. Some were freshly placed. Others a crackly dry brown. An enormous brown wreath of flowers, identical to the one in today’s procession but for the effects of time and heat, stood guard over the small mound of a recent burial. The haphazardly jumbled graves were topped by an equally haphazard jumble of markers – gravestones as tall as a person, simple stones, and humble hand-lettered wooden crosses.

The ceremony went on amid the sweet smell of copal. Continuing his recitations, the priest formed the sign of the cross on the casket lid with dirt poured from a small glass, then used the sprig from the bowl to sprinkle the casket with water. The wife, head covered in a dark grey shawl, approached the casket to say her final farewell. Slowly rocking, arms draped across the casket, she touched her face repeatedly to the casket in grief. The air was saturated with a feeling of sorrow and loss as oppressive as the heat. I put my camera down and wiped my eyes as two women finally led her away, gently holding her shoulders.

The coffin was carefully lowered into the ground. Slowly, under shovelful after shovelful of soil, the coffin disappeared. The funeral was over.

People lingered there in the cemetery, as a low-key fiesta began. While the band played one last song, boxes of tiny Corona bottles and more mescal magically appeared. The women remained clustered beside the grave, talking quietly, and the men stood in small scattered groups, becoming increasingly animated as the alcohol flowed.

Too soon, it was time to leave. I made the rounds, saying goodbye to my newfound friends and thanking them for allowing me to be a part of their lives for a day. As I made my way through Teotitlán del Valle’s alley-like streets, I pondered the fact that what was to be one of my most rewarding travel experiences very nearly didn’t happen. What had originally seemed like a battle between photo-voyeuristic urges and a sense of propriety had really been a struggle with fear. I was afraid to take a risk and join the procession because it was an uncomfortable, unfamiliar situation.

In the end, I had taken the plunge and found myself welcomed into the midst of an unforgettable experience. But that would never have happened if I hadn’t forced myself to take a risk and face a little discomfort.

And that’s where the greatest rewards of travel often live. Hiding behind the uncomfortable, wrapped in the scarily unfamiliar. Sometimes you just have to close your eyes and jump. But the payoff is so big we can’t help but keep going back for more. Again and again, and again. “Would you like to carry the casket?”

Yes please, I think I would…say, is there any of that mescal left?